Printed in the Spring 2013 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Creech, Jimmy. "Born to be Lovers" Quest 101. 2 (Spring 2013): pg. 54 - 58.

By Jimmy Creech

Throughout my twenty-nine years as an ordained minister in The United Methodist Church, among my greatest joys was conducting weddings. Every couple was different—some young and some old, some marrying for the first time and some for a second, some rich and some poor, some gay and some nongay— yet their love for each other and their hope for the life they would share were the same. For me, no matter how vulnerable and tenuous (for all things human are), the love that brought the couples together was the reality of God in their lives—and in the world.

Throughout my twenty-nine years as an ordained minister in The United Methodist Church, among my greatest joys was conducting weddings. Every couple was different—some young and some old, some marrying for the first time and some for a second, some rich and some poor, some gay and some nongay— yet their love for each other and their hope for the life they would share were the same. For me, no matter how vulnerable and tenuous (for all things human are), the love that brought the couples together was the reality of God in their lives—and in the world.

When I counseled couples prior to their weddings, I reminded them that I would not "marry" them, and neither would the church or state. The love they had for each other and the commitment they made in their most intimate moments created their marriage long before any public ceremony or legal recognition.

On Sunday, September 14, 1997, in the sanctuary of First United Methodist Church, Omaha, Nebraska, I conducted a wedding ceremony for Mary and Martha. It was a simple but profoundly moving event: two persons pledged their love and faith to each other before their families, friends, and God. I prayed God's blessings upon them; I prayed that their life together and their home would be filled with God's grace and peace. Their union was recognized by neither the church nor the state. Nonetheless, it was a sacred and solemn moment that honored the marriage they had created.

On Monday morning, all hell broke out in The United Methodist Church. My bishop, Joel Martinez, informed me that more than 150 complaints against me had been filed in his office, accusing me of "disobedience to the Order and Discipline of The United Methodist Church" because I'd conducted a wedding ceremony for two women. The bishop chose one of the complaints to represent them all and initiated a judicial process that would ultimately end in a church trial in March 1998. While I would be acquitted in this trial, I was found guilty in a second trial in 1999, and my credentials of ordination in The United Methodist Church were taken from me for conducting another wedding for a same-gender couple.

Just one year before Mary and Martha's ceremony, the General Conference of The United Methodist Church had adopted language prohibiting its clergy from conducting union ceremonies for same-gender couples. I was in strong disagreement with this prohibition and had informed Bishop Martinez and the lay leadership of First United Methodist Church that I would conduct Mary and Martha's wedding in spite of the prohibition. Mary and Martha were members of First Church and deserved to have their loving commitment to each other honored and recognized in the context of their faith community. To deny them this would have been an injustice and expression of bigotry.

I strongly disagreed with my church on same-gender marriage and felt compelled to celebrate ceremonies for lesbian and gay couples because of Adam, who confided to me in April 1984 that he was gay. At the time, I was the pastor of a United Methodist church in Warsaw, North Carolina. I'd known and worked with Adam in the church for three years before and was surprised to learn he was gay. He came out to me when he informed me that he was leaving the church because of its antigay policies. He was in his late forties and had been a Methodist all of his life. But he would take the abuse no longer. His decision to leave caused him deep anguish. His revelation changed my life and ministry. I tell this story in my book Adam's Gift: A Memoir of a Pastor's Calling to Defy the Church's Persecution of Lesbians and Gays.

Adam was a leader in the church and community. He was generous, gentle, and kind, a person of deep and devout faith He did not fit the stereotype I had about homosexuals. My attitude and understanding of homosexuality was negative, a prejudice shaped entirely by the heterosexism and homophobia of the Southern culture in which I lived, a prejudice I had accepted without critical reflection. I assumed gay people would be psychologically unhealthy and physically dangerous. And before Adam I'd never talked with anyone who self-identified as gay.

Adam did not destroy my assumptions about gay people by offering a new interpretation of the Bible or some theological insight. He destroyed them with his dignity, with his character. My prejudice had no defense against the integrity of his humanity.

After Adam came out to me, I reflected on my personal history, about what I'd learned about homosexuality and about how I developed my negative attitude toward gay people. I first learned about homosexuality when I was a boy from what my friends said about Pee-wee. They said he was a "queer." Nobody explained to me what that meant, except to say that "queers do bad things to little boys like you." I sensed this meant something violent and sexual in nature. Pee-wee was four or five years older than I, and I feared him. As I grew into adulthood, my fear was never challenged.

But Adam's humanity banished my childhood fear of Pee-wee and pushed me beyond my personal experience to study and search for a deeper understanding about the basis for the religious and cultural prejudice against homosexuality. My undergraduate degree from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill was in biblical studies. The issue of homosexuality in the Bible was never discussed during my four years of study. Nor was it discussed during my three years of study at the Divinity School of Duke University Nevertheless, I had accepted without question the conventional claim that the Bible says homosexuality is a sin.

Eager to understand, I studied every piece of biblical scholarship I could find on the subject. At the end, my conclusion was that there is no legitimate use of the Bible to condemn same-gender-loving people and their sexual intimacy. There are a few passages (only four that are clear: Genesis 19:1-29; Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13; and Romans 1:26-27) that refer to same-gender sexual activity. In each case, the sexual activity is condemned because it happens within the context of either violent rape or idolatry. There is no reference to same-gender-loving sexual relationships in the Bible, so it cannot be said the Bible condemns them. My search for what the Bible says about homosexuality provided no basis for the claim that it is a sin. Same-gender sexual relationships simply are not an issue within the Bible.

In addition, there was no understanding of sexual orientation in biblical times. Homosexuality, heterosexuality, and bisexuality are variances in sexual orientation that were discovered during the late 1800s through the emerging science of psychology. Only then were these words created to describe the different categories of sexual orientation, a newly discovered innate aspect of the human personality. This is another reason it is false to claim that the Bible says homosexuality is a sin: there was no understanding of sexual orientation and consequently no words in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek for homosexuality in biblical times. We cannot say the Bible condemns something that its writers didn't know about. Medical science and psychology have evolved in understanding sexual orientation so that today there is a consensus that homosexuality, heterosexuality, and bisexuality are equally normal, natural, and healthy aspects of the human personality.

In Adam's Gift, I observe:

The way the Bible has been used against gay people is not unique. It has been misused in similar ways to support other cultural prejudices, practices and institutions, such as slavery, racism, anti-Semitism, sexism, wars, inquisitions, colonialism, and classism. Such misuse does not serve the biblical understanding of God, Christ, or the church. Each misuse, along with the bigotry against gay, lesbian, and bisexual persons, is an offense against God, assaults the souls of God's children, and compromises the ability of the church to be a faithful witness to Jesus Christ. Any use of God's name to condemn the essential humanity of any people is blasphemous. (Creech, 36)

When I did not find the basis for the cultural prejudice against lesbian, gay, and bisexual people in the Bible, I turned to the history of the Christian church for the answer and was not disappointed.

When Emperor Constantine I of Rome officially ended the persecution of the Christian church with the Edict of Milan (313 cr) and gave it favored status, the church fathers [it was an exclusive all-male club] began putting together the first systematic Christian theology. They were obsessed with sexuality. They abandoned the Jewish view that God's creation—the earth and all that dwells upon it—was good; that a human being is a unity of body and spirit; and that sexuality is a blessed gift for lovemaking, shared pleasure, and childbearing. Marriage was discouraged; virginity and chastity were honored. Because many of the early church fathers were monks or hermits, at one time or another in their careers, their views of sex were dominated by ascetic values. Asceticism became the preferred way to commune with God. Because they believed a human being was a spirit trapped in a body, the preeminent challenge for Christians seeking eternal salvation was to deprive and conquer the physical appetites, especially the erotic. (Creech, 38)

The church father whose views on sexuality most influenced the early Christian church's teachings was Augustine of Hippo (354-430 CE). As a young man, before his conversion to Christianity, he was influenced by Manichaeism and Neoplatonism, both dualistic philosophies that considered the physical world to be corrupt and evil, in contrast to the spiritual world, which was regarded as good. Sexuality was physical and consequently sinful. Augustine was the first to associate the fall of Adam and Eve with sexuality, which he regarded as the original sin. He believed sexual desire was the foulest of human wickednesses. Begetting children was the only acceptable excuse for sexual intimacy. Nonetheless, sexual pleasure was always a sin. He was not alone in his negative view of sexuality, and his teaching about it became the standard for the Christian church during the Middle Ages and beyond.

Augustine's teaching separated spirituality and sexuality.

When spirituality is understood as our capacity to connect with and love the Holy, the neighbor, and the natural world, and sexuality is understood as the way we embody ourselves in the world, then spirituality and sexuality are inseparable and interdependent. Sexuality is the embodiment of our connection with realities beyond our individual selves: our spirituality. Spirituality determines the character and values of our embodiment: our sexuality. When the unity of sexuality and spirituality was denied, spirituality was disembodied and sexuality reduced to a physical appetite narrowly defined as lust. Sexual intimacy, consequently, was separated from love and approved only as a necessary evil for the sole purpose of procreation. (Creech, 39)

In his book, Law, Sex, and Christian Society in Medieval Europe, James Brundage observes:

Writers [i.e., medieval Christian theologians] who place primary emphasis on sex as reproduction, therefore, condemn homosexual relations as well as heterosexual oral and anal sex practices and often maintain that even the postures used in marital sex are morally good or bad depending on whether they hinder or promote conception. Those who consider reproduction the primary criterion of sexual morality usually deny any positive value to sexual pleasure . . . Hence they minimize the value of sexual satisfaction as a binding mechanism in marriage. (Brundage, 580)

In the thirteenth century, theologian and philosopher Thomas Aquinas expanded on Augustine's view and specifically categorized same-gender-loving people as sinners. Aquinas used neither the Bible nor the teachings of Jesus to do this. He used instead the philosophy of Aristotle, who lived some 300 years before Jesus. Aristotle proposed that using something according to its design or purpose is good and using something contrary to its design or purpose is evil. Aquinas applied this philosophical theorem to sexual ethics, claiming, as had Augustine, that the sole design and purpose of sexual intimacy was procreation. Samegender-loving people were then, by definition, sinners and unwelcome.

In Sex in History, Reay Tannahill writes:

Just as Augustine ... had given a rationale to the Church Fathers' distaste for the heterosexual act and rendered it acceptable only in terms of procreation, so Thomas Aquinas consolidated traditional fears of homosexuality as the crime that had brought down fire and brimstone on Sodom and Gomorrah, by "proving" what every heterosexual male had always believed—that it was as unnatural in the sight of God as of man ... Homosexuality was thus, by definition, a deviation from the natural order laid down by God . . . and a deviation that was not only unnatural but, by the same Augustinian token, lustful and heretical ... From the fourteenth century on, homosexuals as a group were to find neither refuge nor tolerance anywhere in the Western Church or state. (Tannahill, 159--60)

Aquinas's view of sexuality was made the official teaching of the Roman Catholic Church, and homophobia was institutionalized. Soon after, church laws were enacted that condemned same-gender sexual intimacy, and civil laws became widespread in Europe calling for the violent execution of people caught in or believed to be guilty of it.

"The appalling truth," I conclude in Adam's Gift,

is that the dominant expression of Christian sexual morality that shaped Western culture over the last two millennia, affecting both intimate relationships and social institutions, was formulated during the historical period known as the Dark Ages by celibate men who believed the physical world to be evil, held women in contempt, considered pleasure a vice, and equated sex with sin. They could not have taken us further from Jesus. The course they established led tragically in the wrong direction for the spiritual evolution of humanity. In spite of a vastly superior knowledge of human sexuality, we continue to be victims of their medieval ignorance, fear, and prejudice embedded in the teachings of the Christian church and in archaic civil laws. More tragic than the external violence done to bisexual, gay, and lesbian people is the fact that they have been taught by the Christian church and the society that it has shaped for centuries to hate themselves and believe themselves to be rejected by and separated from God because of their sexuality, because of who they are and whom they love. The Christian antipathy toward same-gender sexual loving comes from the fear of sexuality, not from the Bible. Because of this fear, gay, lesbian, and bisexual people have been oppressed, persecuted, and killed in the name of God and in defense of society. It's a scandalous and shameful history. (Creech, 40)

With this new understanding of the Bible, human sexuality, and church history, I began to challenge my church's teachings and policies about same-gender-loving people. As a pastor, my responsibility was to help people overcome whatever damaged them spiritually—whatever diminished their capacity to trust God's love, to love others, and to love themselves. After Adam came out to me, I discovered my church was teaching lesbian, gay, and bisexual people to fear God's judgment, to fear loving another intimately, and to hate themselves for being who they are. I believe the church cannot be an authentic witness to God's love when it is persecuting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people.

Sexual orientation—whether it is toward the same gender, different gender or both genders—involves more than behavior for sexual gratification. It's a predisposition toward persons of a particular gender for romantic or emotional attraction and bonding. Sexual orientation is primarily about relationships, not behavior. It's about whom one loves, chooses to marry, and creates a family with. To label as sin a person's capacity for a healthy, adult, loving relationship is an act of spiritual violence. Sexual intimacy is one physical way we express our love and commitment, one way we create and sustain the marriage bond.

In the spring of 1990, James and Timothy asked me to conduct a holy union ceremony for them. They attended worship at Fairmont United Methodist Church in Raleigh, North Carolina, where I was then the pastor. They had been together for several years and owned a home together. James was an educator and Timothy, a landscape architect. The celebration of their commitment to each other would be in the backyard garden that Timothy had planted and tended at their home. I accepted their invitation with delight. I would later write about it:

While conducting a holy union for two men was a new experience for me, I didn't think of it as controversial. In fact, it was a rather traditional Christian thing to do. How could I recognize and affirm gay people as individuals without recognizing, affirming and supporting their loving committed relationships? Civil and religious authorities may deny them recognition, but none can invalidate a relationship grounded in love and integrity. Such grounding is the very reality of God, the ultimate authority and blessing. James and Timothy's holy union ceremony, using the traditional United Methodist marriage liturgy with the Eucharist, was the first of many [same-gender weddings] that I would conduct over the remaining years of my ministry. (Creech, 77)

It was because of the dignity and integrity of the couples whose loving commitments I celebrated over the years that I could not and would not comply with my church's prohibition of such ceremonies when Mary and Martha invited me to conduct theirs in 1997.

In 1998, I was invited to preach at The Riverside Church in New York City. In my sermon, "Free to Love without Fear," I told the story of Mary and Martha's covenant ceremony and reflected on its theological significance. I explained that their religious traditions had taught them that God had rejected and condemned them because of who they were and whom they loved. To survive, they left their homes, families, and, they believed, God. Ultimately, their separate journeys brought them to Omaha, Nebraska, where they found each other and a God who had loved them all along. It was, I said,

. . like a homecoming. Not a return to a home they had left behind, but a coming for the first time to a home they had been denied by the religious traditions in which they grew up. While they thought they left God, God never left them. God was the power within each of them that would not let them deny themselves, that nudged them to leave behind the dishonesty and embrace and honor their true selves as a sacred gift. This was God's active gracious love. It did not come from their religious training, nor from the expectations of family and friends. It came from the deepest place within their souls that knew the truth. This is what we Methodists call "prevenient grace," the grace of God, the love of God that comes to us even before we know it's there, and claims, embraces, and empowers us Mary and Martha's covenant ceremony was a victory of faith and love over fear and oppression. It was a sign that they had individually survived their long tortuous journeys and were finally able to love themselves. Once able to love themselves, they were able to love each other. Finally, they were free to love without fear. The Christian church must no longer demand that the Marys and Marthas of the world remain in the closet of fear, rejection, and self-hatred. No, the Christian church must join God in offering to all lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people the assurance of what God has already done: blessed them and their loving with dignity and honor. When I prayed God's blessing upon Mary and Martha, I was only voicing what God already had done. By God's grace, they had been set free from fear and free to love. (Creech, 284)

To be a lover is what it means to be created in God's image. The capacity to love is not just a gift from God. It is God's presence alive and active in our very beings. We are not meant to be alone. It's basic to who we are as human beings to move out of ourselves to bond with someone, and to care for, nurture, empower, and protect the ones we love. We embody God, when we love. There is no such thing as an unholy love.

The freedom to love without fear and judgment is a human right than cannot be denied to anyone by law, religion, or culture. No government, religion, or cultural convention has the authority to tell us whom we cannot love. We are all born to be lovers, free and fearless.

Sources

Brundage, James. Law, Sex, and Christian Society in Medieval

Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Creech, Jimmy. Adam's Gift: A Memoir of a Pastor's Callingto Defy the Church's Persecution of Lesbians and Gays.Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2011.

Tannahill, Reay. Sex in History. Rev. ed. Chelsea, Mich.:

A native of Goldsboro, North Carolina, JIMMY CREECH was an ordained elder in The United Methodist Church from 1970 to 1999. He holds a bachelor of arts in biblical studies from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a master of divinity from the Divinity School of Duke University. Mr. Creech is the author of two books: Rise above the Law: The Appeal to the Jury, The United Methodist Church's Trial of Jimmy Creech (Swing Bridge Press, 2000), and Adam's Gift: A Memoir of a Pastor's Calling to Defy the Church's Persecution of Lesbians and Gays, published by Duke University Press in 2011.

Love is a spontaneous feeling experienced not intellectually but emotionally. It can most easily be felt when seeing a child or animal—a feeling that simply takes over the person who is observing. It is a moment when all feels right with the world. Time no longer seems to exist, and the world feels as if it is moving in slow motion.

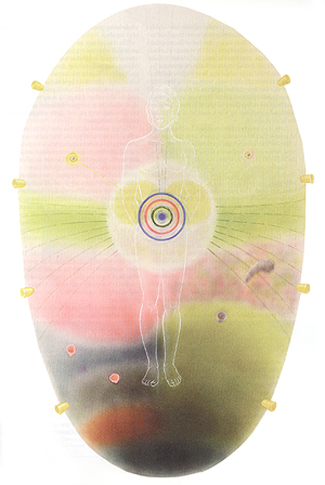

Love is a spontaneous feeling experienced not intellectually but emotionally. It can most easily be felt when seeing a child or animal—a feeling that simply takes over the person who is observing. It is a moment when all feels right with the world. Time no longer seems to exist, and the world feels as if it is moving in slow motion.  Let's look first at the representation of the aura of a pregnant woman. This plate shows the color of a delicate pink both above and below the green band at the woman's center. This represents both the love of her family and the love of the unborn child. Although this plate shows a woman who is seven months pregnant, even at an earlier stage the vibrational energy between mother and unborn child is quite similar. When I am looking at an actual pregnant woman, there is a distinct look of the child, seen as a large, whirling presence, a difficult look to create in a two-dimensional form. The colors of both mother and child complement each other.

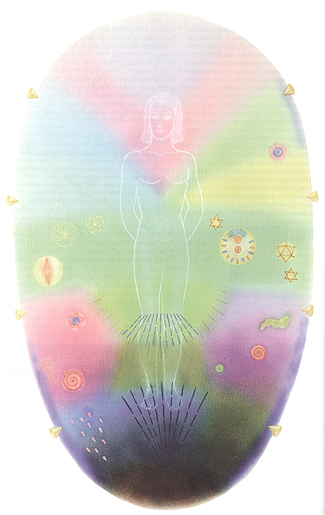

Let's look first at the representation of the aura of a pregnant woman. This plate shows the color of a delicate pink both above and below the green band at the woman's center. This represents both the love of her family and the love of the unborn child. Although this plate shows a woman who is seven months pregnant, even at an earlier stage the vibrational energy between mother and unborn child is quite similar. When I am looking at an actual pregnant woman, there is a distinct look of the child, seen as a large, whirling presence, a difficult look to create in a two-dimensional form. The colors of both mother and child complement each other.  Another plate worth noting shows a painter. Notice the mixture of green with pink; the pink looks like a "V" intersecting her heart and head. This shows the individual's love, and the sheerness of the pink indicates that this is a love she can easily experience.

Another plate worth noting shows a painter. Notice the mixture of green with pink; the pink looks like a "V" intersecting her heart and head. This shows the individual's love, and the sheerness of the pink indicates that this is a love she can easily experience.

The Sanskrit word "kundalini" is literally translated as "coiled." The word is found principally in the lexicon of yogic and Tantric practice and refers to a latent energy or consciousness that resides at a point approximately at the base of the spine. It is usually pictured as either a "coiled serpent" or a "goddess." In either context it is considered feminine and is related to unconscious, instinctive, and/or libidinal forces.

The Sanskrit word "kundalini" is literally translated as "coiled." The word is found principally in the lexicon of yogic and Tantric practice and refers to a latent energy or consciousness that resides at a point approximately at the base of the spine. It is usually pictured as either a "coiled serpent" or a "goddess." In either context it is considered feminine and is related to unconscious, instinctive, and/or libidinal forces.  People tend to analyze love, calling it by various names: unconditional, patriotic, maternal, erotic, platonic, andsoon. Yet how can we accept any one aspect as a definition of love itself? If you are lucky enough to catch sight of a rainbow, you do not wish to stop and scrutinize where a certain color begins and another ends.

People tend to analyze love, calling it by various names: unconditional, patriotic, maternal, erotic, platonic, andsoon. Yet how can we accept any one aspect as a definition of love itself? If you are lucky enough to catch sight of a rainbow, you do not wish to stop and scrutinize where a certain color begins and another ends.  To sit down and write an article on love is a daunting task. With so many authors and great books providing interpretations of love and all that goes with it, who am Ito presume I can add to such a bibliography? Well, I'm a gay man who has experienced same-sex love.

To sit down and write an article on love is a daunting task. With so many authors and great books providing interpretations of love and all that goes with it, who am Ito presume I can add to such a bibliography? Well, I'm a gay man who has experienced same-sex love. Throughout my twenty-nine years as an ordained minister in The United Methodist Church, among my greatest joys was conducting weddings. Every couple was different—some young and some old, some marrying for the first time and some for a second, some rich and some poor, some gay and some nongay— yet their love for each other and their hope for the life they would share were the same. For me, no matter how vulnerable and tenuous (for all things human are), the love that brought the couples together was the reality of God in their lives—and in the world.

Throughout my twenty-nine years as an ordained minister in The United Methodist Church, among my greatest joys was conducting weddings. Every couple was different—some young and some old, some marrying for the first time and some for a second, some rich and some poor, some gay and some nongay— yet their love for each other and their hope for the life they would share were the same. For me, no matter how vulnerable and tenuous (for all things human are), the love that brought the couples together was the reality of God in their lives—and in the world.