The Daimon in Pre-Socratic and Platonic Thought

Printed in the Spring 2025 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Bucci, Dominic, "The Daimon in Pre-Socratic and Platonic Thought" Quest 113:2, pg 23-26

By Dominic Bucci

When we sit back and reflect on the direction of our lives, we can see some hand of guidance that has been instrumental in placing us in our current positions. This often goes unnoticed by many, preventing a deeper entrance into spiritual reality. The touch of guidance is often not noticed until we reflect.

To define daimon is not an easy task, not solely because the term is often ambiguous in translation. While the daimon’s function as a guide has been consistent across time, its position relative to us, both collectively and personally, has not.

For the past several years, I have been studying the ever-unfolding concept of the daimon. I have been looking both at it and through it to gain a new view of the world and my spiritual path.

The daimon is a guide that is unique to each of us, and one that evolves with us as we grow in understanding. It is a guide on our path of immortality, the track that we all follow that is above the mere individual life. When our vision is limited to this life alone, the daimon can sometimes appear to be acting contrary to our best interests. I have found that this is only the case when we fail to view life as an expanded journey of the soul.

The daimon is a living being, a spirit that we have often anthropomorphized by projecting human qualities onto it. For this reason, when it interacts with us outside of human form, it can go unseen or appear ghostly or as coincidence or synchronicity. Nonetheless, it is a part of the experience of being human, no matter what we believe or where or when we were born. The daimon has been observed in some form in every culture and tradition since the beginning of recorded history. Some of its Eastern relatives are the Buddhist yidam (tutelary deity), the Islamic qareen (a kind of spiritual double), and the ishta devata (personal god) of Hinduism.

The English word daimon (plural daimones) is derived from the Greek δαίμων (daimon). The concept is quite distinct from the stigmatized word demon. According to Liddell and Scott’s unabridged Greek lexicon, daimon is probably derived in turn from δαίω (daio), meaning to distribute (lots or fates): indeed, as we will see, daimon is sometimes translated as fate. Sometimes in ancient Greek the word was used to indicate divine power, as opposed to θεός (theos), which refers to a god in a personal sense. In other cases, daimon indicates a supernatural being somewhere in between gods and humans. In still other cases, daimon was used as more or less equivalent to theos. As is often the case, the meaning was often determined by the context. Daimon in the original Greek is a living concept.

The Origins of the Daimon in the West

At a time when prophets were poets, the daimon emerged in the epic poetry of Homer and Hesiod. Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey portrayed the daimon as both a guardian spirit watching over individuals and as the forces of fate influencing destiny—the common thread being that of a supernatural, external force governing over being.

In the eighth century BC, Hesiod discussed the origin of the daimones in his epic Works and Days by introducing the European myth of the ages of man, which divided the history of the world into five eras. The first was the Golden Age, when humans lived in an Edenic paradise as gods, knowing no sorrow or toil on earth and living in harmony. These first humans lived lifespans of many hundreds of years. When they died, they simply went peacefully to sleep, and their spirits became the daimones that were to guide the mortals who came during the subsequent ages. The daimones were seen as the lingering essence of the Golden Age, embodying its ideals by providing beneficent guidance.

At this point, before the Greeks had thoroughly developed the concept of psyche or “soul,” the daimon was seen as a force outside and separate from us. Later, once the concept of the soul had been fleshed out, the daimon could also be found to be acting from within, the relationship moving from outer to inner.

The Pre-Socratic Daimon

The daimon features prominently in the thought of the Greek philosophers of the sixth and fifth centuries BC, who preceded Socrates and are known as the pre-Socratics. One of them, Heraclitus, is known for the often quoted maxim: “Character is daimon [fate] for the human.” His contemporary Parmenides referred to the daimon as “the divinity that steers all things.” Empedocles, who introduced the concept of four elements of fire, air, water, and earth, explained that the daimon was a force of pure love on a cosmic path of return. With his teachings, the focus began on the daimon that is individual and present.

Socrates

The Athenian Socrates (c.470‒399 BC) is regarded as a kind of founding figure of Western philosophy. The dialogues of Plato, almost all of which feature Socrates prominently, are our principal source of knowledge about him, since Socrates left no writings of his own.

Socrates experienced one of the earliest recorded relationships with a personal daimon, with whom he was in constant contact since childhood, although he had not gained access to it through conscious practice, spiritual devotion, or any type of religious ritual. Socrates’ daimon appeared as an inner voice that frequently warned him against potential mistakes or harmful actions. His daimon did not tell him what to do, only what to avoid. It acted as a kind of internal veto. Its mode of operation was to ensure that he did not stray from the path assigned to him by the gods.

Socrates’ frequent references to his daimon formed part of the charges brought against him by the state of Athens in 399 BC. The Apology of Socrates, written by Plato but ostensibly a record of Socrates’ speech in his own defense, details his trial. He was accused of “introducing new gods” as well as corrupting the youth of Athens with his ideas.

Socrates was condemned to death by forced suicide. Before his death, his pupils provided the means for his escape to another city and urged him to flee, but he refused. Instead he decided to drink the poison hemlock as ordered and accept his sentence. Socrates’ daimon made sure that he fulfilled the pattern of his faith and the significant destiny it was.

Socrates mentioned that a daimon’s task is to interpret and convey human things to the gods and divine things to humans; being in the middle, the daimon can supplement each. In Plato’s Symposium, Socrates says, “God does not mix with men, but through the daimonic all association and converse comes between the gods and men, whether sleeping or awake.”

It was therefore with Socrates that the concept of the daimon began to shift from that of occult forces that took hold of people in mysterious ways and made them act under their influence to that of a guide that worked to keep the soul from straying from its assigned path. Socrates made a conscious bond with his inner guide. Whereas previously the daimon had been primarily viewed as a source outside of a person’s control, Socrates experienced it as an inner intimate relationship.

Socrates advised communing with one’s daimon in order to comprehend the gods through the deeds they perform in the world rather than waiting for them to reveal themselves to us.

Plato

While Socrates can be credited with originating the idea of the personal daimon, Plato played a crucial role in disseminating the idea of the daimon as a superior or divine part of the soul. He also shaped our understanding of it as a protector and guide for the individual during this life and the life to come.

Plato introduced the philosophical idea of deifying all beings through a direct personal bond with the divine realm of the “Forms.” He also explained that the psyche existed before and after life on earth and undergoes a process of repeated incarnations until it achieves a state of purity.

Plato regarded the physical world as unreal as opposed to an incorporeal, unchangeable other world, which is to be regarded as primary. Plato placed the ego in an immortal soul that is alien to the body and captive in it.

Plato’s Allegory of the Chariot

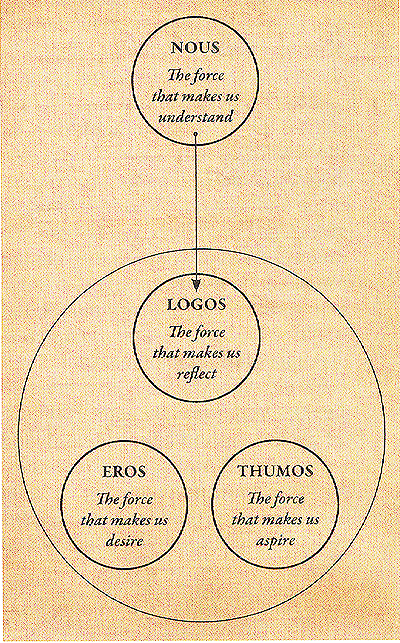

In his dialogue the Phaedrus Plato developed his concept of the soul through the allegory of the chariot. He divided the soul into three distinct parts: the charioteer or driver and two horses pulling the chariot. The charioteer represents the logos, or the force that makes us reflect. One horse, a noble one, represents thumos, or the force that makes us aspire. The other, unruly horse represents eros, the force that makes us desire. Eros is driven by the sensual impressions of the world and our bodily appetites. Thumos is driven by social norms and expectations, like courage, ambition, and honor. The logos is the pure capacity for mental reflection but can generate nothing by itself; by this understanding, it can only process the data provided by the eros and thumos. The success of the tripartite soul relies on the harmonious interaction of all the soul’s components.

|

|

|

An Illustration from Achille Bocchi, On a Universal Range of Symbolic Inquires, at Which He Played Seriously, 1555. The Greek word on the plinth at lower right says, "Socrates." The Greek at lower left says, "Daimon, Eudaimon" : that is daimon and "good daimon" or tutelary spirit' Socrates claimed to have a daimon, a guiding spirt who advised him throughout his life. |

The higher part of the soul, situated above and in contact with the logos is the nous (or consciousness). Its function is to understand nature in an unbiased and undistorted fashion, remaining pure and untouched, beyond the imitations of illusory reality. While the logos receives its sense impressions filtered through eros and thumos, it also receives undistorted information from the nous, which intuitively provides a higher form of insight.

The nous is often understood as the divine or spiritual assistance that humans receive to help comprehend reality, acting as a living spiritual force that draws true reasoning from flawed perceptions. The function of the nous in the human soul is to unite the ephemeral nature of matter with the eternal spirit behind it. According to Plato, nous was implanted in humans as something divine—as a daimon.

When the nous is recognized and integrated into the tripartite soul, it opens up space for the daimon to emerge separate from the mental functions of the psyche. The charioteer-driver must tame the horses in order to hear the voice of the daimon. The importance of this point cannot be stressed enough: we must learn how to handle the world’s distractions in order to establish this contact with the daimon for guidance.

When Plato located the daimon inside the soul, he identified it with “an upper part,” which is immortal and divine and at the same time representing an ideal to which the human soul aspires. This upper, divine part of the soul wishes to escape the state of servitude and disequilibrium to which its mortal parts hold it. Plato stated, “As concerning the most sovereign form of soul in us, we must conceive that heaven has given it to each man as a daimon, that part which we say dwells in the summit of our body and lifts us from earth towards our celestial affinity, like a plant whose roots are not in earth, but in the heavens.”

The daimon, as nous, can be understood as the part of the soul that stands as a mediator between the earthly realm and the celestial sphere, as a living, spiritual chain that connects all humans to their eternal higher self.

By deifying the nous, Plato laid the foundation for all the philosophical, occult, and religious traditions of a personal and immortal divine being assigned to and watching over every incarnated human. Plato discussed the daimon in many of his dialogues, particularly in the tenth and last book of The Republic, with its myth of Er.

The Myth of Er

This myth recounts the tale of a soldier named Er, who has been left for dead in battle but who has merely fallen into a coma. When he awakens after twelve days, he tells of his journey in the afterlife. This includes information about reincarnation, the astral plane, and the daimon.

After being struck down on the battlefield, Er awakens on the astral plane and finds himself in a vast meadow filled with souls. Er sees two openings leading in and out of the sky, and two leading in and out of the underground. Judges sit between these openings and judge the souls based on their lives. These judges then tell the souls the path they are to follow: the good are guided into the sky, and the immoral are directed below. When it is Er’s turn to approach the judges, he is told to remain, listen, and observe in order to report his experience back to humankind.

|

|

| A schematic diagram of Plato;s concept of the Soul. |

Er watches as souls return from both the sky path and the underground path. From the sky, the souls return and recount beautiful sights and wondrous feelings. From the underground, the souls return haggard, dirty, tired, and crying in despair; recounting horrible experiences—as each has been required to pay a tenfold penalty for all the wicked deeds they committed when alive.

After this experience, the souls are required to travel farther, and they reach a place where they can see a brilliantly bright shaft of rainbow light that extends upwards into the sky and resembles a giant spindle. Er describes this spindle as having celestial spheres that orbit around it in a perfect circle. The spindle turns in the lap of a personified Necessity, whose daughters, the Fates, are present around it.

The souls are organized into rows and are selected according to a lottery to come forward and choose their next life. Er observes a man who has not known the terrors of the underground, but has been rewarded in heaven, hastily choose a powerful dictatorship. Upon further inspection of this life, the man finds that he is going to commit many atrocities. Er notes that this is often the case for those who have been through the path in the sky, whereas those who have been punished often choose a better life.

The step that precedes the reincarnation of the soul is the choosing of a daimon that will accompany the soul to help it through its new life until its next reincarnation. Each soul is then required to drink some of the water of the river of forgetfulness. Er is not permitted to drink any at all, so he can remember his experience when he returns to earthly life. As they drink, each soul forgets everything it has just experienced. As the souls lie down to sleep, each is lifted up into the night in various directions for rebirth, completing their journey.

Er remembers nothing of the journey back into his body. He opens his eyes to find himself lying on a funeral pyre early in the morning, but able to recall his journey through the afterlife.

A central theme in the myth of Er is the importance of personal choice in shaping one’s destiny. Souls are presented with a variety of lives to choose from, and this choice determines their future experiences. The daimon acts as a guide and guardian, helping the soul navigate the consequences of its choice. This emphasizes the idea that individuals are responsible for their own lives and the choices they make.

The idea of the human soul as immortal—and the realization that we are more than merely corporeal—provided space for the daimon to exist. This led to an understanding of a higher self beyond the lower ego. When we can appreciate the daimon and find him—in history, in mythology, in philosophy, in psychology, and in religion—we have created space for contact.

In the Platonic world, human lives were seen intertwined with nature, and things and events were understood to occur cyclically in balance. Evil was considered more of an imbalanced temporary state that could be corrected rather than existing as an independent force in its own right.

When Christianity formulated its religious duality of good and evil, the daimon became demonized. An internal connection to divinity became something to fear as demonic rather than as a place of looking within oneself to find guidance and connect directly with God. Westerners were now required to have an intermediary on our behalf—a disempowerment would last for hundreds of years until Theosophy and other esoteric traditions reopened the possibility of direct connection.

Dominic Bucci is a federal contractor, property developer, and graduate student in the East-West psychology department at the California Institute of Integral Studies.

On the afternoon of October 24, 1917, just four days after their wedding, Georgie Hyde-Lees, the young bride of the middle-aged poet W.B. Yeats, decided to try her hand at automatic writing, the practice of allowing spirits to communicate through the written word.

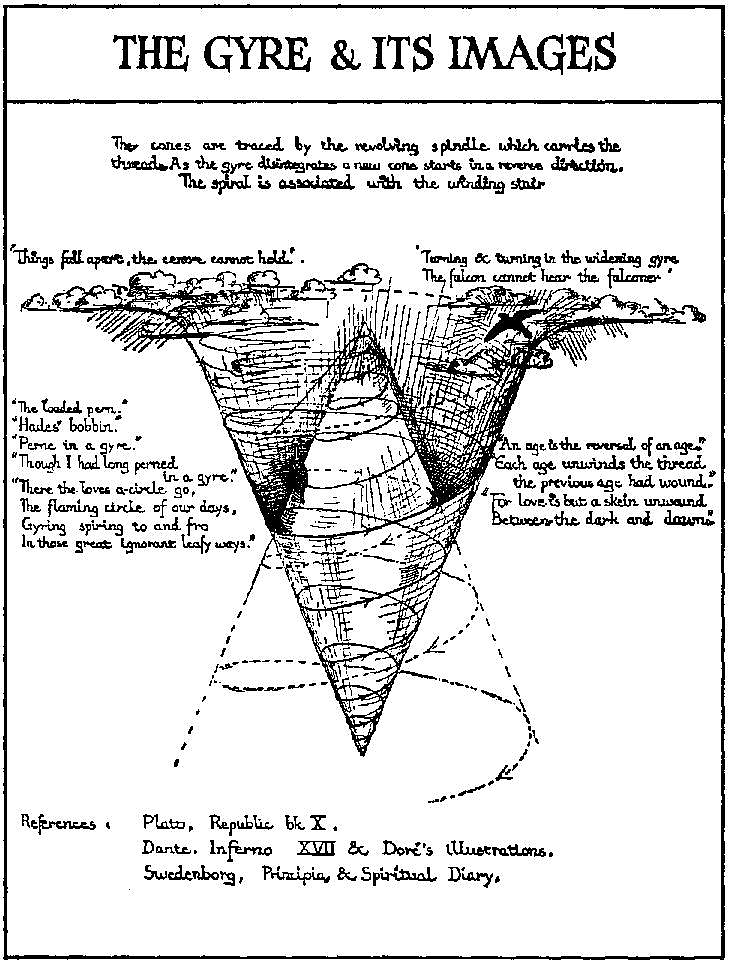

On the afternoon of October 24, 1917, just four days after their wedding, Georgie Hyde-Lees, the young bride of the middle-aged poet W.B. Yeats, decided to try her hand at automatic writing, the practice of allowing spirits to communicate through the written word. Nevertheless, Yeats discovered that material from these semitrance states seemed to relate to an idea he had put forth in his early poetry collection Per Amica Silentia Lunae: some men develop through their battles with themselves, others through their battles with the world (what Jung would have called the “introverted” or “extraverted” paths).

Nevertheless, Yeats discovered that material from these semitrance states seemed to relate to an idea he had put forth in his early poetry collection Per Amica Silentia Lunae: some men develop through their battles with themselves, others through their battles with the world (what Jung would have called the “introverted” or “extraverted” paths).

Kripal: I know a bit about the John Mack case. John did address these phenomenological accounts in a direct way. He was a psychiatrist at Harvard, as you mentioned, which means he was in the scientific or medical world. I’m in the humanities or the study of religion, which nobody cares about, basically, and they don’t think we know anything anyway.

Kripal: I know a bit about the John Mack case. John did address these phenomenological accounts in a direct way. He was a psychiatrist at Harvard, as you mentioned, which means he was in the scientific or medical world. I’m in the humanities or the study of religion, which nobody cares about, basically, and they don’t think we know anything anyway.