Printed in the Winter 2025 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Smoley, Richard, "The Blavatsky Letters" Quest 113:1, pg 17-24

In early 2025, the Theosophical Publishing House, completing a longstanding project, is publishing the second volume of The Letters of H.P. Blavatsky, edited by the late Jon Knebel with the assistance of Sharron Dorr, Janet Kerschner, and Nancy Grace. This volume includes letters from the years 1879 to 1883

In early 2025, the Theosophical Publishing House, completing a longstanding project, is publishing the second volume of The Letters of H.P. Blavatsky, edited by the late Jon Knebel with the assistance of Sharron Dorr, Janet Kerschner, and Nancy Grace. This volume includes letters from the years 1879 to 1883

Some brief excerpts of these letters appear below.

They have been chosen with a view to clarifying certain misconceptions about the early Theosophical Society that have been propagated by some academic scholars.

One issue has to do with the relation of HPB to the spiritualist movement of her day. She, along with her associate Henry Steel Olcott, had been intimately involved with it, agreeing that spiritualist mediums were actually communicating with the dead. But at around the time of the Society’s founding in 1875, the Mahatmas ordered them to execute what HPB below calls a “volte-face”: an about-face. She and Olcott repudiated the idea entirely, now contending that the supposed spirits of the dead were nothing more than the discarded astral shells of the deceased (which she sometimes called “spooks”). Both she and Olcott were ordered by their Mahatmas to preach against the spiritualist doctrine, leading the movement to denounce her as a traitor.

As the letters below reveal, HPB was initially attached to spiritualism, based largely on her childhood experiences with an allegedly dead woman known below as Mrs. T—— L——. But in the end she learned that this lady was still alive. Blavatsky was forced to conclude that her contacts had been merely readings of some impressions gleaned from the astral light, along with cryptomnesia (forgotten memory).

Another issue: some scholars have contended that there were in effect two Theosophical Societies in the first decade of the organization’s existence, the first dating from the organization’s founding in 1875 to the departure of HPB and Henry Steel Olcott for India in 1878‒79. Supposedly “Western” in origin, this first TS taught the tripartite division of the human entity into three parts (spirit, soul, and body). After HPB and Olcott went to India, they supposedly came under Eastern influences, now expounding a sevenfold division of the human entity and promoting a supposedly second and different Theosophy, more Eastern in influence.

Letter 294 below indicates the truth: the supposedly Western tripartite division is not contradicted by the later seven-part division: the second schema is merely a subdivision of the first. Other scholarly claims about “two Theosophical Societies” can also be refuted, although they cannot be addressed here.

These comments suggest how a movement such as the TS can be misunderstood and misrepresented by those outside it.

Richard Smoley

Letter 191

August 3, 1880

Bombay

[To C. Augustin Bilière]

I do not know if I am a “great soul,” but I know that I would much prefer not to have any at all and to see it obliterated together with the body. This old carcass has plagued me for a long time and my “great soul” has only caused ingratitude and calumnies; hence, it is only an “idiot.” But—this is my personal opinion, if you please, and the Theosophical Society has nothing to do with it. I am a Buddhist to my finger tips, and I have said so for years. I believe in the soul, but a material soul which finally disappears, as should be the case with every honest soul and with every particle of matter, neither the form nor the duration of which can consequently be either infinite or immortal.

I believe in the eternity of matter as a principle, never as form, which is always temporary. I do not believe in the personal immortality of the soul or of the Ego; but I believe in the immortality and the eternity of the Universal Spirit or of the impersonal and Unique Ego; and it is then that my poor little “great soul,” finally merged with and absorbed by the great All, will find its annihilation, its Nirvana, and where it will finally rest in Universal Nothingness from its miserable and stormy existence. The feverish activity will be submerged in Spiritual Inactivity, the poor little individual atom in the Universal All; and then H.P. Blavatsky, from a small drop of muddy water, will have become a limitless Ocean, without beginning or end.

Such is my aspiration! I’ll never be content to end up by settling down as an individual soul, whether in Nirvana or in the traditional Paradise. It would be a pretty sight indeed—the souls of James, Peter, and Susie sprawling out in Eternity with golden toothpicks in their mouths and the Beings’ coats of arms adorning their door curtains. Very philosophical, that idea. My own ambition is finally to become the All, to be at last drawn to and absorbed in Nirvana as a drop of vapor is drawn to the Ocean; and there, losing my personal individuality, to replace it by the Impersonal individuality of the Universal Essence, which the Christians and other deists call “God,” and that I and my school (which is not the Theosophical school) call the Universal Cause; cause which has neither intelligence, nor desire, nor will, because it is absolute Intelligence, Desire, and Will.

Letter 226

Bombay,

December 5, 1881

[To Prince A M. Dondukov-Korsakov]

I was 35 when I saw you for the last time . . . I stayed a few weeks at Odessa with my aunt Mme. De Witte, who is still there. While there, I received a letter from a Hindu whom I knew 28 years ago in London, in extraordinary circumstances, and who made me undertake my first journey to India in 1853. In England I saw him only twice and at our last interview he said to me:

“Your destiny lies in India, but later, in 28 or thirty years. Go there and see the country.” I went there—why, I do not know! I was as in a dream. I stayed there nearly two years, travelling about and receiving money each month—from whom I have no idea, and following faithfully the itinerary given to me. I received letters from this Hindu, but I did not see him a single time during those two years. When he wrote to me: “Return to Europe and do what you like but be always ready to return”—I took my passage on the Gwalior which was wrecked near the Cape, but I was saved with some twenty others. Why did this man exercise such an influence over me? I do not yet know the reason. But had he told me to throw myself into an abyss I would not have hesitated an instant. I was afraid of him without knowing why, for no man has ever been gentler or simpler. Should you want to know more about this man, then read when you have time From the Caves and Jungles of Hindustan in Moscow Chronicle, where I write under the pen name of “Radda-Bai.” Order them to send you the pamphlet edition. My Hindu appears therein under the name of “Thakur Gulab Singh.” You will see there what he has done, the extraordinary phenomena attributed to him, etc. . . . I am sure it will interest you. Now he has left India for ever and has settled in Tibet (where I can go when I like, though neither Pjrevalsky nor any Englishman will enter therein, I can assure you)—and from Tibet he corresponds with the English members of our Society, keeping them entirely under his mysterious domination . . .

In 1869 I left for Egypt and from there went again to India returning in 1872. Then, having received at Odessa, in 1873, a letter in which my mysterious Hindu told me to go to Paris, I went there in March 1873 (the 2nd I think). As soon as I arrived, I received another, telling me to embark for North America, which I did without protesting. From there, I had to go to California, then to Yokohama where, after 19 years of separation, I saw once more my Hindu whom I found settled in a little palace, or country house, about three or four miles from Yokohama. I stayed but a week, for he sent me back to New York, after giving me detailed instructions. As soon as I arrived, I set to work. To begin with he made me preach against Spiritualism, which raised against me the 12 million “Innocents” in the United States who believe in the return in flesh and bones of their mothers-in-law, dead and eaten by worms years ago, and of their premature offspring who had forgotten to be born, but who, once discarnate, grow and increase in stature up there (for the exact locality consult the Spiritualists’ geography). What I told them in my public lectures before 4 or 5,000 people, I could not tell you. However, while believing I was talking nonsense, it appears that . . . without knowing it, I gave them eloquent addresses, which after two years led to the birth of the Theosophical Society. Founded by myself and Colonel Olcott, formerly a rabid Spiritualist, but since meeting me, a Buddhist and an Occultist in the manner of the Rose-Croix of the Middle Ages—as fanatical an anti-Spiritualist—the Society grew visibly. All the Spiritualists, disappointed in their materialized mothers-in-law—who had forgotten in the next world the names of their daughters; all the ex-bigots, protesting against Protestantism, Catholicism, Spiritualism and other “isms,” swallowed the bait of the new philosophy that fell from the sky and became members of our Society. At the end of a year, in 1875, it was 8 to 9 thousand members strong. Then, another letter forced me to give up my lectures (Colonel Olcott taking my place) and to start and finish a book of 1,400 closely printed pages, in two large volumes called Isis Unveiled. I will not speak of it, as there is not a paper that has not mentioned it, either to tear it into a thousand pieces, or to compare it to the greatest works of philosophers past, present and to come. I wrote it quite alone, without anyone beside me to help me, in English which I then hardly knew; but, as during my lectures, it seems I wrote classical English without a mistake, quoting in support of that which I was saying from known and unknown authors, from books of which only one solitary copy existed, either in the Vatican or in the Bodleian Library, to which I could not have had access, but which in the course of time would serve to verify what I had written and avenge me on my detractors, for every word I had written was found to be correct. This work was and still is a sensation. It has been translated into several languages—among them into Siamese and Hindu, and it is—the Bible of our Theosophists. Did I write it myself? No, it was my hand and my pen. For the rest I give it up, as I myself did not understand it in the least at the time, nor do I now. The fact is that 10,000 copies of the first edition at 36 shillings we sold the first month, from which in fact I got as profit only honour and not a penny, for believing it was mere idle talk that would not be worth a single edition, I sold it to an Editor-Publisher for a song, as the saying goes, while he made over 100,000 dollars, it being in its 6th edition for the past 3 years. And there we are.

Letter 228

[December 1881]

[Probably to A.O. Hume]

For over six years, from the time I was eight or nine years old until I grew up to the age of fifteen, I had an old spirit (Mrs. T——L—— she called herself), who came every night to write through me, in the presence of my father, aunts and many other people, residents of Tiflis and Saratoff. She gave a detailed account of her life, stated where she was born (at Revel, Baltic Provinces), how she married, and gave the history of all her children, including a long and thrilling romance about her eldest daughter, Z—— and the suicide of her son F——, who also came at times and indulged in long rhapsodies about his sufferings as a suicide.

The old lady mentioned that she saw God and the Virgin Mary, and a host of angels, two of which bodiless creatures she introduced to our family, to the great joy of the latter, and who promised (all this through my handwritings) that they would watch over me, &c., &c., tout comme il faut [“everything just as it must be”].

She even described her own death, and gave the name and address of the Lutheran pastor who administered to her the last sacrament.

She gave a detailed account of a petition she had presented to the Emperor Nicholas, and wrote it out verbatim in her own handwriting through my child’s hand.

Well, this lasted, as I said, nearly six years—my writings—in her clear old-fashioned, peculiar handwriting and grammar, in German (a language I had never learnt to write and could not even speak well) and in Russian— accumulating in these six years to a heap of MSS that would have filled ten volumes.

In those days this was not called spiritualism, but possession. But as our family priest was interested in the phenomena, he usually came and sat during our evening I with holy water near him, and a goupillon (how do you call it in English?) [“aspergillum,” used to sprinkle holy water] and so we were all safe.

Meanwhile one of my uncles had gone to Revel, and had there ascertained that there had really been such an old lady, the rich Mrs. T——L——, who, in consequence of her son’s dissolute life, had been ruined and had gone away to some relations in Norway, where she had died. My uncle also heard that her son was said to have committed suicide at a small village on the Norway coast (all correct as given by “the Spirit”).

In short all that could be verified, every detail and circumstance, was verified, and found to be in accordance with my, or rather “the Spirit’s,” account; her age, number and name of children, chronological details, in fact everything stated.

When my uncle returned to St. Petersburg he desired to ascertain, as the last and crucial test, whether a petition, such as I had written, had ever been sent to the Emperor. Owing to his friendship with influential people in the Ministère de l’Interieur, he obtained access to the Archives, and there, as he had the correct date and year of the petition, and even the number under which it had been filed, he soon found it, and comparing it with my version sent up to him by my aunt, he found the two to be facsimiles, even to a remark in pencil written by the late Emperor on the margin, which I had reproduced as exactly as any engraver or photographer could have done.

Well, was it the genuine spirit of Mrs. L—— who had guided my medium hand? Was it really the spirit of her son F—— who had produced through me in his handwriting all those posthumous lamentations and wailings and gushing expressions of repentance?

Of course, any spiritualist would feel certain of the fact. What better identification, or proof of spirit identity; what better demonstration of the survival of man after death, and of his power to revisit earth and communicate with the living, could be hoped for or even conceived?

But it was nothing of the kind, and this experience of my own, which hundreds of persons in Russia can affirm—all my own relations to begin with—constitutes, as you will see, a most perfect answer to the spiritualists.

About one year after my uncle’s visit to St. Petersburg, and when the excitement following this perfect verification had barely subsided, D........, an officer who had served in my father’s regiment, came to Tiflis. He had known me as a child of hardly five years old, had played constantly with me, had shown me his family portraits, had allowed me to ransack his drawers, scatter his letters, &c., and, amongst other things, had often shown me a miniature upon ivory of an old lady in cap and white curls and green shawl, saying it was his old aunty, and teazing [sic] me, when I said she was old and ugly, by declaring that one day I should be just as old and ugly.

To go through the whole story would be tedious; to make matters short, let me say at once that D—— was Mrs. L——’s nephew—her sister’s son.

Well, he came to see us often (I was 14 then), and one day asked for us children to be allowed to visit him in the camp. We went with our Governess, and when there I saw upon his writing-table the old miniature of his aunt, my spirit! I had quite forgotten that I had ever seen it in my childhood. I only recognized her as the spirit who for nearly six years had almost nightly visited me and written through me, and I almost fainted. “It is, it is the spirit,” I screamed; “it is Mrs. T——L——.”

“Of course, it is, my old aunt; but you don’t mean to say that you have remembered all about your old play thing all these years?” said D. . . . who knew nothing about my spirit-writing. “I mean to say I see and have seen your dead aunt, if she is your aunt, every night for years; she comes to write through me.” “Dead?” he laughed, “But she is not dead. I have only just received a letter from her from Norway,” and he then proceeded to give full details as to where she was living and all about her.

That same day D——was let into the secret by my aunts, and told of all that had transpired through my mediumship. Never was a man more astounded than was D——and never were people more taken aback than were my venerable aunts, spiritualists, sans le savoir [“without realizing it”].

It then came out that not only was his aunt not dead, but that her son F........., the repentant suicide, l’esprit souffrant [“the suffering spirit”], had only attempted suicide, had been cured of his wound, and was at the time (and may be to this day), employed in a counting house in Berlin.

Well then, who or what was “the intelligence” writing through my hand, giving such accurate details, dictating correctly every word of her petition, &c., and yet romancing so readily about her death, his sufferings after death, &c., &c.? Clearly despite the full proofs of identity, not the spirits of the worthy Mrs. T—- L—-, or her scapegrace son F——, since both these were still in the land of the living. “The evil one,” said my pious aunts; “the Devil of course,” bluntly said the Priest. Elementaries, some would suppose, but according to what —— has told me, it was all the work of my own mind. I was a delicate child. I had hereditary tendencies to extra-normal exercise of mental faculties, though, of course, perfectly unconscious then of anything of the kind. Whilst I was playing with the miniature, the old lady’s letters and other things, my fifth principle (call it animal soul, physical intelligence, mind, or what you will,) was reading and seeing all about them in the astral light, just as does the mind of a clairvoyant when in sleep; what it so saw and read was faithfully recorded in my dormant memory, although, a mere babe as I was, I had no consciousness of this.

Years after, some chance circumstance, some trifling association of ideas, again put my mind in connection with these long forgotten, or rather I should say never hitherto consciously recognized pictures, and it began one day to reproduce them. Little by little the mind, following these pictures into the astral light, was dragged as it were into the current of Mrs. L . . .’s personal and individual associations and emanations, and then the mediumistic impulse given, there was nothing to arrest it, and I became a medium, not for the transmission of messages from the dead, not for the amusement of elementaries, but for the objective reproduction of what my own mind read and saw in the astral light.

It will be remembered that I was weak and sickly, and that I inherited capacities for such abnormal exercise of mind—capacities which subsequent training might develop, but which at that age would have been of no avail, had not feebleness of physique, a looseness of attachment, if I may so phrase it, between the matter and spirit, of which we are all composed, abnormally, for the time, developed them. As it was, as I grew up, and gained health and strength, my mind became as closely prisoned in my physical frame as that of any other person, and all these phenomena ceased.

How, while so accurate as to so many points, my mind should have led me into killing both mother and son, and producing such orthodox lamentations by the latter over his wicked act of self-destruction, may be more difficult to explain.

But from the first all around me were impressed with the belief that the spirit possessing me must be that of a dead person, and from this probably my mind took the impression. Who the Lutheran Pastor was who had performed the last sad rite, I never knew—probably some name I had heard, or seen in some book, in connection with some deathbed scene, picked out of memory by the mind to fill a gap, in what it knew.

Of the son’s attempt at suicide I must have heard in some of the mentally read letters, or have come across it or mention of it in the astral light, and must have concluded that death had followed, and since, young though I was, I knew well how sinful suicide was deemed, it is not difficult to understand how the mind worked out the apparently inevitable corollary. Of course, in a devout house like ours, God, the Virgin Mary and Angels were sure to play a part, as these had been ground into my mind from my cradle.

Of all this perception and deception, however, I was utterly unconscious. The fifth principle worked as it listed; my sixth principle [buddhi] or spiritual soul or consciousness was still dormant, and therefore for me the seventh principle [atman] at that time may be said not to have existed.

But I am straying from my purpose, which simply was to show that the most perfect proofs of spirit identity, I mean apparent proofs, are utterly fallacious, and that spiritualists, who base their theories on these supposed proofs, are truly building their house upon the sand.

Letter 231

Bombay,

January 31, 1882

[Addressee unknown]

“Come to our side”—the spiritualists tell us—“confess your belief in departed Spirits, & half of your burden will fall off your shoulders. You will have 20 millions of Spirits to defend you, to suffer with you”—“Never”! we answer; for we do not believe in departed Souls coming back to earth to show how much more idiotic & dull they have become in a “better world”! The world in general & sceptics especially deny the existence of the Brotherhood of our 1st section. Let them deny & be happy. Yet, there are some dozen or more persons who have seen them not only at our headquarters but elsewhere, and a few Fellows of our Society, life-long residents in India (I do not mention Hindus, as those who know our Brothers may be reckoned by thousands) who knew the adepts years before the Theos. Society came to India. Hence it is not H.P.B. who “invented them.” And to wind up, some of our members have seen those recluses since Mr. Sinnett’s book appeared. If you require their names & addresses I will cheerfully furnish them; you will find them among the most trustworthy persons (Europeans) in India . . .

The Adepts of Tibet do not belong to the Nepâl Agnostics—if so you call them, though I fancied that their belief in Swabavât and its potentialities & knowledge of its actual possibilities would hardly merit that name. Our Brothers are Spiritualists in the nobler sense of the word; they are Occultists or Lha-pa (believers in invisible beings) and teach a philosophy which approximates Vedantism but is superior to it and not personifying that Eternal Principal [sic] whose alternate conditions of activity & passivity are indicated in the successive condition & dispersion of the objective universe . . .

You would “pay a prince’s ransom” to believe in the miraculous status of Koot Hoomi. Give up any such idea; he has no miraculous or super-natural being or powers. Our Brothers do not believe in “miracles” and discard with contempt the very thought of them being any thing super or outside of nature. He is but one of many men who have penetrated the Mysteries, by the ancient and invariable methods. If you had honoured us with your acquaintance at New York you might have seen his portrait hanging on the wall, & even caught a glimpse of himself—for he walked past one of our windows one evening in full view of several visitors. This fact (without his name of course) was reported in the World, when one of whose reporters was there.

Letter 235

Bombay,

1 March 1882

[To Prince A.M. Dondukov-Korsakov]

I have nothing to hide. Between the Blavatsky of 1845–65 and the Blavatsky of the years 1865–1882 there is an unbridgeable gulf. If the latter seeks to put the extinguisher on the former, it is more for the sake of human honor than for her own personal one. Between the first and the last there is the Christ and all the celestial Angels and (with) the Holy Virgin, and after the last there is the Buddha with his Nirvana and the bitter and cold conception of the sad and ridiculous fiasco of the creation of the first man in the image of and likeness of God! The first should have been annihilated even before 1865, and that in the name of humanity capable of producing in the world such a mad curiosity. As for the last, she sacrifices herself, for the first one believed and prayed, thinking that by her prayers her sins would be forgiven, placing her hope in the non compos mentis [“not of sound mind”] of humanity as a whole, in the common madness which is the result of civilization and cultured society—and the second one believes only in the negation of her own personality in its human form, and that the end of all being Nirvana, Where neither prayer nor faith in an abstraction can help, since all depends on our Karma (personal merit or demerit) . . .

You may have heard—or maybe would not listen to the rumour—that my great grandfather on my mother’s side, Prince Paul Vasilyevitch Dolgorouki, had a strange library containing hundreds of books on alchemy, magic and other occult sciences. I had devoured these volumes before the age of 15. All the devilries of the Middle Ages had found refuge in my head and soon neither Paracelsus, Khunrath nor C. Agrippa would have had anything to teach me. All of them spoke of the “marriage of the red Virgin with the Hierophant,” and of that of the “astral mineral with the Sibyl,” of the combination of the feminine and masculine principles in certain alchemical and magical operations. Do you know why I married old Blavatsky? Because, whereas all the young men laughed at “magical” superstitions, he believed in them! He had so often talked to me about the sorcerers of Yerivan, of the mysterious sciences of the Kourds and the Persians, that I took him in order to use him as a pass-key to the latter. But—I never was his wife, I swear it by the very hour of my death. NEVER have I been “wife Blavatsky” although I lived for a year under his roof. Neither have I been anybody’s wife as evil tongues have pretended—for I was for about ten months in search of the “astral mineral” that had to have the “red Virgin” pure and entire, but I did not find that mineral. What I wanted and searched for was the subtle magnetism that we exchange, the human “salt,” and father Blavatsky did not have it; and to find it and obtain it, I was ready to sacrifice myself, to dishonour myself! This did not suit the old man, hence quarrels, nearly battles, till I ran away from him and came to Tiflis from Yerivan—on horseback—where I went into hiding with my grandmother. I swore that I would commit suicide if forced to return to him. Ah! how sad they did not let me do as I wished! Married during the spring of 1848, in the month of February (or January) 1849 I was still in search of my “salt” and human “mineral” and—the “Virgin” was still there in the full sense of the word, whilst all the time people were tearing my reputation to pieces at Tiflis!

Letter 293

Adyar

June 1, 1883

[To D.A. Courmes]

You are able to picture to yourself what is the One Life. You have defined it marvelously well. It is precisely that—“God in the Universe”—where everything that is has always been and will eternally remain, not as a form, as the latter changes every moment, but as substance; the latter, one and indivisible, from the mineral atom to the highest Deva, resolves itself in Parabrahm. Spirit or superior pole, matter or opposite pole. The manifested and the unmanifested, the temporary and the Eternal. We do not recognize inorganic matter. Every atom has its divine spark and is a particle of spirit, or, so to say, of petrified divinity. The essence is one, but conditions change. Take for instance sound; strike or imagine to yourself the most melodious note self-existent in eternity; this note resounds forever as itself, immaculate and melodious; whether it finds itself imprisoned in a beautiful piano or violin, where conditions for it are favorable, or whether it is left free, surrounded by natural conditions, in a forest for instance, the result is a melody. But let it be caught in an old dilapidated instrument, and even under the most skillful fingers it would result in nothing but a cacophony, a terrible discord.

Well, you will understand me; I can hardly express myself in French. But I see that you understand truth perfectly and your intuition is admirable. You are a Buddhist!

Letter 294

Adyar, Madras. June 23

1883

[To Nikolai Petrovich Wagner]

Why did we do a “volte-face,” Colonel and I? Because we were told by those in whom we believe more than in ourselves—“either preach the truth—or farewell.” I know that Alexander Nikolayevich doesn’t believe in this by more than two thirds. But if he just thinks about it, and you too, what’s in it for us to go against the whole world? Against spiritualists, deists, believers and sceptics, against “the god and the devil,” as the proverb goes. Wouldn’t it be a thousand times easier to follow the same old track, just digging new, inconspicuous paths. What’s my profit, what’s my reward? That all Anglo-Indian journals labelled me an adventurer, a liar, a Russian spy etc. etc., and spiritualist journals would do the same if they were not afraid of me. Some American ones actually did say all those things about me. Look how much they respected me in America at first, when they didn’t know about my real card. And from the day the Society was founded, everything just turned upside down. You weren’t following this story, you don’t know how much we suffered for the truth. Alexander Nikolayevich doesn’t believe either in Morya, or “Kuthumi—Mahatma.” He’s mistaken. They are both real people, many personally met them in India, especially the former. He came to Bombay, and Olcott saw him at least twenty times in his own body, not in an astral one. I’ve known him since 1853, and had I listened to him, I wouldn’t be so sorrowful now, I would be living just like all ordinary people. Do you know why I didn’t believe him? Because I strongly believed in an anthropomorphic god and not in One Divine Essence, in the Holy Spirit (ours, not yours), like I do now. They call me an atheist? Well, I reply that I used to be much worse than an atheist, I was an idolatress until the age of 30, while I believed in things that everyone believes in. Now I believe—because I know and I’m not afraid of dying, I’m waiting for death as deliverance. And Olcott believes in the same thing as I do, because we’ve taken the same path. We didn’t “hop from one belief to another,” we just decided to remove the mask, in which we used to believe ourselves. Having learned the truth and the entire truth, without a shadow of a doubt, we decided to stop lying to people, as well as to our own conscience. It’s a sin to blame poor Olcott—especially him, who gave everything and lost everything for the truth—his motherland, his children, the respect of all his relatives and society, who view him as a crazy enthusiast that literally became poor and ascetic and lives on a bit of rice and milk. So I’m saying, it’s a sin to blame him without hearing out the truth. You can treat me as you like: I deserved it in my past. But now, the pure spirits that I believe in and that I know exist—see that I serve the truth and the truth only; and if I were to burn at the stake tomorrow—I am ready.

And now—perhaps—you should learn about what we believe in, even though we respect the faith of others—whatever they might believe in—and we leave it be. We don’t consider ourselves infallible, and we know that there are many, many things that neither we, nor our Himalayan adepts (as they realize themselves to be) can know, because none of them—even the highest planetary spirits or Archangels, as you would call them—can see beyond the shroud of our solar system—so we don’t dogmatize. The things that we know, we know for certain from our own experience, but we never impose this knowledge on others. What for? A man can only believe as much as his intellectual abilities allow him to, not more than that. If it were possible to analyze our psychic feelings as easily as our brain after death, there wouldn’t be two people believing in something in the same way. What’s truth for me can be a misconception for you and—vice versa. I don’t have any right to preach my own beliefs like mathematically proven axioms. Absolutely no right. That’s why I’m with you when you say that I can be wrong. I certainly can—but not in front of my own conscience and not when I speak about things that are as clear as day to me. But you keep asking questions, you’re asking to enlighten you. I refuse to do the latter, but I’m ready to tell you everything that I’m allowed to say in The Theosophist—I’m at your disposal.

We divide the human being into three main parts: a physical, a semi-material and a purely spiritual one—that means we believe in a divine, immortal Ego. This trinity is subdivided into seven elements (it’s too long to explain and to go into metaphysical detail). You’re a scientist and you should know that everything that’s objective in the world has three aspects; and everything that’s subjective—four (Pythagoras’ tetraktys). I give examples that you’re more familiar with, from Greek mysticism and philosophy, since you didn’t study either Buddhistic or Brahmanical esoterism. Instead of laughing, without understanding what it’s all about, like Mendeleev did, he should have tried to understand what we mean by the “absurdity” of the quadrature of the circle. It’s the greatest mystery, la solution de ce problème [“the solution to this problem”] and it’s the only thing in the mental world that’s capable of proving to anyone in the world that the spirit is immortal and that there is a god—and it’s not extra cosmic but it’s out side of ourselves—call it Christ, Krishna, Avalokiteswara, Logos—Word—whatever, it’s all one and the same thing. Has anyone ever seen god out side of themselves? Your science will never get to the great mystery: only the “quadrature of the circle” can make you face the “One Truth” in practice (of course, in the psychic sense). We divide the matter into seven—I don’t what you call it in Russian science, forgive my ignorance—seven states or conditions. You’ve always known three of them, the fourth one—“the radiant matter”—was discovered by Crookes. There are three left. Seek, and ye shall find. We believe that the synthesis of everything is One. It’s universal, ubiquitous, uncreated and eternal, with no beginning and no end—there are seven beams coming from it. Science confirms this in the spectrum—one white beam, and six and seven starting from it. Spirit and matter—same thing. The spirit belongs to the seventh class—beyond the Cosmic matter. There’s only manifested and unmanifested matter . . .

That’s why, believing in the spiritual (purely spiritual) Ego, in “son in father and father in son,” we name the “spirit” according to this one principle. The spiritual soul of the person is inseparable from him; but in order for the person’s personality, his terrestrial Self (i.e. yours—professor Wagner’s, or mine) to merge with the spiritual monad and transfer to the eternity—to the adobe of pure spirits—one has to develop in oneself, i.e. in one’s animal Self, with the mind and consciousness of one’s own personality—le moi conscient [“the conscious I”], the spiritual consciousness, not just the animal one. This spiritual soul, l’ame spirituelle [“the spiritual soul”] is like an endless thread, a forming beam during cycles or periods of a conscious life, passing from one personality (terrestrial) into another. Personalities, like pearls, one after another, string onto it (reincarnation). Upon the moment of death of the physical person, his body, his animal essence and his first ethereal sheath each return to its element. There are four principles left: 1. Animal soul. 2. Consciousness of your own personality, i.e. Peter’s or Ivan’s,—or Mind. 3. Spiritual soul and 4. Spirit—different from the Primeval Essence only in the fact that it’s manifested, while the Essence is an unmanifested spirit. Thousands of years pass between every new materialization and the previous one . . . This time can be either rewarding or punishing for the soul. We believe in Karma, i.e. in consequences of every action—a good or a bad one. Every single word and every single thought leave a trace in the eternity. There is only one law in nature, it is inviolable, and this law is God. Let’s assume that the animal Self generated enough spiritual Karma in itself (for example, Love, an immortal and the most spiritual feeling). The spiritual soul, together with the life-giving spirit, is filled, replete with the essence of all personal feelings inherent in the animal Ego, and it separates from the terrestrial semi-ethereal sheath of the animal soul and the terrestrial material Ego, and departs to purely spiritual regions . . .

Now, while the pure soul, the spiritual Ego, departed to spiritual regions (it’s not a place, it’s une condition, un état [“a condition, a state”]), there is only shell left in the world of forms—what the Greek called αïδης [“Hades”]. This shell is the sediment of the terrestrial Ego that outlives the body, but when it is left without the life-giving spirit, it cannot be called a “spirit.” These shadows are your materialized kikimory, vampires, sucking the juices that they need for this artificial life out of mediums, using the brain and the memory of both the medium and everyone else around. This “current of mediumship”—that Mendeleev and Tindal have no idea about—the electricity of a living being influences the shell of the deceased person like a galvanic battery influences a corpse. Neither the “spirit” or the medium is to blame. The former acts unconsciously, instinctively, and the latter is irresponsible.

In Greek mythology, the flying winged ram Chrysomallos was the offspring of Poseidon, the god of the sea, and Theophane, the daughter of Bisaltes, who in turn was the son of Helios and Gaia (Sun and Earth).

In Greek mythology, the flying winged ram Chrysomallos was the offspring of Poseidon, the god of the sea, and Theophane, the daughter of Bisaltes, who in turn was the son of Helios and Gaia (Sun and Earth).

I recently attended a lecture on basic metaphysics at a large senior residential community. The speaker, a Theosophist, was explaining the different dimensions of subtle energies that comprise the human aura: the densest level being the vital or etheric field that interpenetrates the physical body and extends two to four inches from the surface of the skin; the emotional field, being less dense, interpenetrates the vital field and extends farther from the body; the mental field, even more rarefied, has higher and lower frequencies corresponding to abstract and concrete thought patterns.

I recently attended a lecture on basic metaphysics at a large senior residential community. The speaker, a Theosophist, was explaining the different dimensions of subtle energies that comprise the human aura: the densest level being the vital or etheric field that interpenetrates the physical body and extends two to four inches from the surface of the skin; the emotional field, being less dense, interpenetrates the vital field and extends farther from the body; the mental field, even more rarefied, has higher and lower frequencies corresponding to abstract and concrete thought patterns.

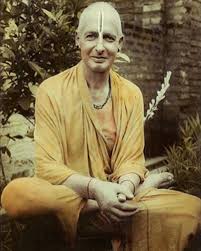

One of the most influential Theosophical writers of the mid‒twentieth century, Sri Krishna Prem is nevertheless rarely mentioned in the same breath as other famous alumni of the post-Blavatsky Theosophical Society. Even J. Krishnamurti (whose public rejection of Annie Besant and C.W. Leadbeater earned him the label gurudrohi—betrayer of the guru—from Krishna Prem) achieved his later fame largely on the strength of his affiliation with Theosophy.

One of the most influential Theosophical writers of the mid‒twentieth century, Sri Krishna Prem is nevertheless rarely mentioned in the same breath as other famous alumni of the post-Blavatsky Theosophical Society. Even J. Krishnamurti (whose public rejection of Annie Besant and C.W. Leadbeater earned him the label gurudrohi—betrayer of the guru—from Krishna Prem) achieved his later fame largely on the strength of his affiliation with Theosophy. In early 2025, the Theosophical Publishing House, completing a longstanding project, is publishing the second volume of The Letters of H.P. Blavatsky, edited by the late Jon Knebel with the assistance of Sharron Dorr, Janet Kerschner, and Nancy Grace. This volume includes letters from the years 1879 to 1883

In early 2025, the Theosophical Publishing House, completing a longstanding project, is publishing the second volume of The Letters of H.P. Blavatsky, edited by the late Jon Knebel with the assistance of Sharron Dorr, Janet Kerschner, and Nancy Grace. This volume includes letters from the years 1879 to 1883