Printed in the Spring 2017 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Smoley, Richard, "The Mystery of the Seven Seals" Quest 105:2 (Spring 2017) pg. 30-34

By Richard Smoley

Until baptism . . . fate is true. But afterward the astrologers are no longer correct.

—Excerpta e Theodoto, 78.

The New Testament is probably the most widely read book in the world. And yet it is also a book that is mysterious and not fully understood. In some cases, this is because what the churches teach today no longer corresponds with what the New Testament says. This is the case with the nature and person of Jesus. (See my article, “The Strange Identity of Jesus Christ,” in Quest, fall 2015.) In other instances, it is not so much that the teaching has been changed, but that it has been lost completely.

The New Testament is probably the most widely read book in the world. And yet it is also a book that is mysterious and not fully understood. In some cases, this is because what the churches teach today no longer corresponds with what the New Testament says. This is the case with the nature and person of Jesus. (See my article, “The Strange Identity of Jesus Christ,” in Quest, fall 2015.) In other instances, it is not so much that the teaching has been changed, but that it has been lost completely.

This is true of the early Christian view of cosmology. It is peppered throughout the New Testament but has been completely overlooked or forgotten. The result is that many parts of the text are baffling or incomprehensible today.

Here’s one example—the angels. Today angels are golden-haired beauties who save you from car wrecks. There is even a magazine, Angels on Earth, that is devoted to printing readers’ experiences of encounters with angels. It has a circulation in the hundreds of thousands.

But in the first century AD it was not so. Here is a curious fact: in the New Testament, the apostle Paul never speaks of angels in a favorable way. Examples: “For I am persuaded, that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor powers, nor things present, nor things to come, . . . shall be able to separate us from the love of God” (Romans 8:38–39; biblical quotations are from the King James Version). “For I think that God hath set forth us the apostles last, as it were appointed to death: for we are made a spectacle unto the world, and to angels, and to men” (1 Corinthians 4:9; emphasis added in both passages).

In both examples, the angels are not friends of humanity but barriers to God.

To understand the implications of this fact, it might be best to begin with the cosmological worldview that was current in the first century CE. It is based on the seven planets as known at that time: the moon, Mercury, Venus, the sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. They were believed to revolve around the earth, each in its own crystalline sphere. Beyond these was the realm of the fixed stars, and beyond that, God himself.

In English the word heaven has two meanings, one having to do with the physical sky (usually in the plural form heavens), the other having to do with the spiritual realm. The ancient Greek word ouranós had a similar dual sense. The heavens above, including the spheres of the planets, were regarded both as physical space and as a spiritual dimension.

It’s difficult for us today to understand this worldview. Although we do think of heaven in the spiritual sense as being “up there,” we understand it as a metaphor only. The realms of the physical planets and stars in outer space, to our minds, have no spiritual component.

In antiquity it was not so. The physical heavens were identified with the levels through which the soul had to ascend after death. These levels, and the planets associated with them, were, as often as not, viewed as a series of gates that blocked the soul from its ascent to its true home.

Each of these planets had a vice associated with it, which is where we get the concept of the seven deadly sins. The soul could only ascend if it shed these vices. The process is described in the Poimandres, a treatise that makes up part of the Corpus Hermeticum or “Hermetic body” of writings, generally dated to the early centuries of the Common Era:

The human being rushes up through the cosmic framework, at the first zone [the moon] surrendering the energy of increase and decrease; at the second [Mercury] evil machination, a device now inactive; at the third [Venus] the illusion of longing, now inactive; at the fourth [the sun] the ruler’s arrogance, now inactive; at the fifth [Mars] unholy presumption and daring recklessness; at the sixth [Jupiter] the evil impulses that come from wealth, now inactive; and at the seventh [Saturn] the deceit that lies in ambush. (Poimandres, 1.25)

Each of these seven spheres was also ruled by a planetary archon, who could be viewed as an angel or as a god.

The New Testament also taught that these planetary spheres were ruled by corrupt forces. The epistle to the Ephesians, according to most scholars, was not written by Paul, but it is close to his thought. It says: “For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in [heavenly] places.” (Ephesians 6:12. The word “heavenly,” in the King James Version, appears in a note. But it is closer to the Greek epouraníois than is the reading in the main text, “high places.”) This verse makes it clear that the “principalities” and “powers” were not the Roman emperors, but “spiritual forces of evil.” Paul himself in Romans 8:38–39 (quoted above) uses more or less identical terms in the same way.

Let’s go ahead 500 years, to the single most important Christian work on angelology: the Celestial Hierarchy of Dionysius the Areopagite.[*] He lists orders, or “choirs,” of angels, each class having a different name. Two of these are the “Principalities” and “Powers.” Pseudo-Dionysius’s system was taken up by Dante in his Divine Comedy, among others.

Notice the change here. For Paul and the author of Ephesians, writing in the first century, the “principalities” and “powers” are among the forces of “wickedness in heavenly places.” For Pseudo-Dionysius, writing 500 years later, they are honorable members of the heavenly hierarchy.

It would be an intricate task to show when and how this change came about. For our purposes, it’s enough to know that it did come about. Thus the mainstream Christian view of the angels as unilaterally benevolent simply does not go back to the earliest times of the faith.

In fact, among the early Christians—at any rate among the ones who wrote the New Testament—there was a widespread belief that the celestial realms were occupied by evil forces. The struggle of the Christian was to rise above them, to contend with them, and possibly to defeat them.

This theme too appears throughout the New Testament. In Luke 10:18 we find a mystifying verse. It appears in this context: Jesus has sent out seventy disciples to preach his message. They return “with joy, saying, Lord, even the devils are subject to us through thy name.” Jesus replies: “I beheld Satan as lightning fall from heaven.”

A similar idea appears in John 12:31: “Now is the judgment of this world: now shall the prince of this world be cast out.”

The upshot of all these details is clear: the authors of the New Testament believed that somehow Satan and the forces of “spiritual wickedness” had ensconced themselves in the celestial spheres, and that it was the task of Christ (and his followers) to cast them down. The verse from Luke quoted above makes it sound as if this has already happened: the verses from Paul and Ephesians suggest that the struggle was still going on.

To understand this picture more fully, we will have to turn the most enigmatic book of the Bible: Revelation.

| |

![Theosophical Society - The Seven Chakras Theosophical Society - A diagram from Pryse’s Apocalypse Unsealed illustrating the seven chakras along the spine, and their connections with symbols in Revelation. Pryse uses isopsephy (Greek numerology) to identify some of the key figures and symbols in the text. [*] Dionysius the Areopagite is a figure mentioned in Acts 17:34 as a contemporary of Paul. This work is attributed to him, but was very likely written 500 years later, in the sixth century CE. Hence the author, otherwise unknown, is often called “Pseudo-Dionysius.”](/files/publications/questmagazine/spring2017/The_Gnostic_Chart.jpg) |

| |

A diagram from Pryse’s Apocalypse Unsealed illustrating the seven chakras along the spine, and their connections with symbols in Revelation. Pryse uses isopsephy (Greek numerology) to identify some of the key figures and symbols in the text.

[*] Dionysius the Areopagite is a figure mentioned in Acts 17:34 as a contemporary of Paul. This work is attributed to him, but was very likely written 500 years later, in the sixth century CE. Hence the author, otherwise unknown, is often called “Pseudo-Dionysius.”

|

Revelation has a grip on the Western imagination like no other work. In Doctor Zhivago, Boris Pasternak wrote, “All great, genuine art resembles and continues the Revelation of St. John.” Its images and themes have long since soaked into the popular imagination: the Beast, the Whore of Babylon, the number 666, the Four Horsemen. Nonetheless, very few have managed to pull its narrative together and explain it in terms that might have made sense to its original audience in the first century CE.

But it is possible to do this in light of the ideas I have sketched out above.

To begin with, a very brief sketch of this enigmatic book: John—traditionally associated with Jesus’s “beloved disciple,” although he probably did not write it—has a vision of the “Son of man” among seven golden candlesticks, which represent seven churches, all of them in Asia Minor. The messages are unenthusiastic at best: to the one in Ephesus, for example, he says, “I have somewhat against thee, because thou hast left thy first love” (Revelation 2:4).

Then John has a vision of heaven, where he sees “seven lamps of fire burning before the throne, which are the seven Spirits of God.” A book with seven seals is presented, and these seals are opened, each revealing some new and terrible manifestation: the renowned Four Horsemen, “a great earthquake,” and cosmic cataclysm: “The stars of heaven fell unto the earth . . . And the heaven departed as a scroll when it is rolled together” (Revelation 6:12–14).

When these are completed, seven angels sound seven trumpets, with similar tribulations: a star named Wormwood falls upon the waters of the earth, “and the third part of the waters became wormwood: and many men died of the waters, because they were made bitter” (Revelation 8:11).

Finally, the climactic moment arrives: “And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon: and the dragon fought and his angels. . . . And the great dragon was cast out, that old serpent, called the Devil, and Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him” (Revelation 12:7, 9).

The images in Revelation have been used so often, and in so many ways, that certain facts have become obscured. In the first place, the vision does not have to do with some imagined end of the world in the immeasurably remote future. It is something that the prophet sees as happening in his own time.

In the second place, we may wonder why the number seven is repeated and emphasized to an almost maniacal degree. In the light of what we’ve already seen, the reason becomes clear: it has to do with the realms of the seven planets. They have been inhabited by corrupt forces, including evil angels. The opening of the seven seals and the blast of the seven trumpets culminate in a war in which all of them, led by Satan, are cast down from the heavens onto the earth. Revelation appears to be describing a great purge of the cosmic realms that, the prophet believes, has been initiated by Christ, “the Son of man,” “the Lamb.” (Remember the line from Luke in which Jesus says he sees Satan falling “as lightning” from heaven.)

At this point the action switches to earth. Then ensues “the judgment of the great whore that sitteth upon many waters.” She sits on “a scarlet-coloured beast, . . . having seven heads.” The text explains, “The seven heads are seven mountains, on which the woman sitteth” (Revelation 17:3, 9). The identification of this woman and beast are obvious: it is Rome, which was built on seven hills. It has “seven kings. Five are fallen, and one is, and the other is not yet come; and when he cometh, he must continue a short space.” If we identify them with the Roman emperors, the first five are Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero, who was overthrown in 68. By this reckoning Galba would be the sixth, although he reigned for only seven months. This takes us up to 69 CE, known as “the year of the four emperors,” because four emperors followed one another in quick succession. The prophet believes that there will be another, but that he will not be around long, and that he will be the last. The prophet was partly right. Galba was followed by Otho, who ruled for a mere three months, but Otho was far from the last. The line of Roman emperors continued on for centuries.

If this is actually what John has in mind, we find ourselves in the midst of the Jewish War (66–73 CE), in which the Jews revolted against Rome. It would seem that the prophet is writing around this time, and he expects it to usher in the Last Judgment, which will end in a final battle with the result that “Babylon the great is fallen” (Revelation 18:2). After that, the prophet sees “a new heaven, and a new earth, and the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven” (Revelation 21:1–2).

If this is what the prophet foresaw, he was wrong. The Jews were crushed. The Temple in Jerusalem was sacked and Judea itself partly depopulated. Rome, the “great whore,” was not overthrown, and celestial forces did not descend to destroy it. The Roman Empire continued to last for centuries. The Last Judgment did not occur. Nor did the world end.

|

|

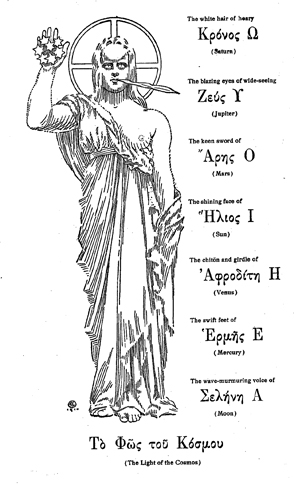

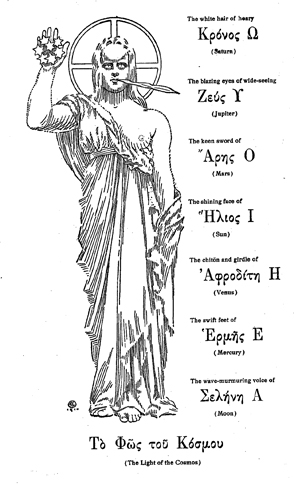

An illustration from James Morgan Pryse’s Apocalypse Unsealed, connecting the seven gods (and planets) with seven levels in man. Pryse also associates each of the seven Greek vowels with these levels.

|

|

In any event, we can sum up the action of Revelation as follows: Christ, the Lamb, is slain and resurrected. He ascends into heaven and purges the seven heavens of evil influences, led by Satan. They are cast down to earth, and are embodied in the Roman Empire, which itself will be crushed by heavenly forces led by the Lamb, culminating in a new world.

I can’t claim to understand the entire symbolism of Revelation, which is profound and multilayered, but I am willing to say that this, at least in part, is what is going on here. Nevertheless, we still face one major question. Why and how did the heavenly realms come to be infested with evil influences?

One answer appears in the passage from the Poimandres that I quoted above. Here the planetary zones seem to be identified with evil propensities. Could the Hermetic texts—of which the Poimandres is a part—be the sources of this doctrine of “spiritual wickedness in heavenly places”? Or could both the texts and this doctrine have come out of the same stream?

It is possible. Scholar Brian Copenhaver observes that the Hermetic texts “can be understood as responses to the same milieu, the very complex Greco-Egyptian culture of Ptolemaic, Roman, and early Christian times”—meaning the long period between the fourth century BCE and the second century CE. This was also the milieu in which Christianity arose. One may have influenced the other, or they may both derive their ideas from a common source.

The Poimandres does not portray these cosmic forces as inherently evil. When the cosmic man is created, it is said that the seven “governors”—of the planets, that is—“loved the man, and each gave a share of his own order.” But man, like Narcissus, fell in love with his image in the natural world, and fell. Thus his nature is twofold: immortal, given by God, and mortal, born of his infatuation with matter. He is in bondage to things over which he should be master. The qualities that the “governors” gave him become vices that he has to overcome.

The Hebrew Bible hints of similar things. Over and over we encounter entities called “the host of heaven” or “the sons of God.” Here is one example. The prophet Micaiah says, “I saw the Lord sitting on his throne, and all the host of heaven standing by him on his right hand and on his left” (1 Kings 22:19). In this passage, the host of heaven is part of Yahweh’s heavenly court, and thus part of the cosmic order.

But here is another verse. It is a warning given to the children of Israel by Moses, “lest thou lift up thine eyes unto heaven, and when thou seest the sun, and the moon, and the stars, even all the host of heaven, shouldest be driven to worship them, and serve them, which the Lord thy God hath divided unto all nations under the whole heaven” (Deuteronomy 4:9).

In fact many references in the Hebrew Bible to the “host of heaven” amount to warnings against worshipping them, or condemnations for having done so.

The host of heaven plays an ambiguous role in the Hebrew Bible. Again these beings—personifications of the stars and the planets and the signs of the zodiac—are not necessarily evil; they are part of the celestial court. At the same time there is a strong temptation to worship them that is repeatedly and vehemently denounced. As in the Poimandres, man is not meant to worship the seven heavenly “governors” or to be subject to them.

The ascent portrayed in the Poimandres has to do with the fate of the soul after death. The ascent through the spheres happens to the virtuous, those who obey this divine dictum: “Let him <who> is mindful recognize that he is immortal, that desire is the cause of death, and let him recognize all that exists.” (The bracketed insertion is the translator’s.) Salvation here comes from gnosis: insight into one’s own true nature and estate. One who lacks such insight, “the one who loved the body that came from the error of desire goes on in darkness, errant, suffering sensibly the effects of death.”

But there is another thread that we need to take up at this point. It is initiation. As is often said, initiation is a kind of death and rebirth. On the simplest level, this has to do with a death to one’s former life and a birth to a new, higher life. But there is more to it than that. In a famous passage, Cicero, the great Roman statesman and philosopher, writes about initiations into the mysteries: “So in very truth we have learned from them the beginnings of life, and have gained the power not only to live happily, but also to die with a better hope” (Cicero, Laws 2.14.36; my emphasis).

This theme keeps appearing around the ancient mysteries. They have to do with death, not merely in a symbolic sense, but in a highly practical one. In some way they prepare the candidate for death; they make the process that he undergoes in the afterlife easier and more assured of success. It seems likely to me that the pagan mysteries had more than a little to do with this process. The mysteries of Mithras in fact took place in seven stages of initiation, which were very likely connected to the seven planets.

We then turn back to the epigraph of this article, a quotation from the Excerpta e Theodoto (“Excerpts from Theodotus,” a Gnostic figure from the second century CE): “Until baptism . . . fate is valid. But afterward the astrologers are no longer correct.” Christian baptism, viewed esoterically, raises the candidate up beyond the levels of the seven planets, which rule fate. The initiate is free from the influence of the planets and thus from fate.

This passage also emphasizes that liberation is not merely due to a rite but is the result of gnosis. It goes on to say: “It is not only the cleansing that is liberating, but the knowledge [gnosis] of who we were, and what we have become, where we were or where we have been thrown, where we hasten, what we are cleansed of, what birth is and what rebirth is” (Excerpta e Theodoto, 78; my translation).

Thus, at least for some early Christians, baptism was correlated with a liberating ascent through the realms of the planets, whose associated vices had been made inoperative. The initiate reaches a level of consciousness and being that is above the domain of the planets.

The Theosophist who examined these questions most thoroughly was James Morgan Pryse (1859–1942), an associate of both H.P. Blavatsky and William Q. Judge. In 1910 he published The Apocalypse Unsealed, an esoteric interpretation of Revelation. For Pryse, Revelation is about initiation—indeed he translates the Greek word apokálupsis as “initiation.” Here too initiation is a liberation from the spheres of the seven planets. They are embodied in us as the seven chakras, which he connects with the seven principal ganglia of the nervous system (Pryse, 16–18; see illustration). Initiation is an ascent through these spheres of the planets—again, the chakras. The famous beast whose number is 666 is not Nero but, numerologically, hē phrēn, the lower mind, centered in the heart (Pryse, 26).

Certainly much of this teaching has been obscured over the centuries. A typical Christian today would be unlikely to recognize it. The view of the planetary spheres as benign completely supplanted this older view, and then the idea of the spheres was abandoned altogether.

But did any fragment of this early teaching survive in later Christianity? Yes, it did—in a curious form. Eastern Orthodox teaching refers to “aerial tollhouses” that the soul must pass through while ascending after death.

Seraphim Rose, a twentieth-century American Orthodox monk, writes, “The particular place which the demons inhabit in this fallen world, and the place where the newly-departing souls of men encounter them—is the air” (emphasis Rose’s). He quotes a liturgy written by John Damascene in the eighth century: “When my soul shall be about to be released from the bond with the flesh, intercede for me, O Sovereign Lady [i.e., the Virgin] . . . that I might pass unhindered through the princes of darkness standing in the air.”

The metaphor of aerial tollhouses is in fact used. Another passage from John Damascene: “O Virgin, in the hour of my death rescue me from the hands of the demons, and the judgment, and the accusation, and the frightful testing, and the bitter toll-houses.” At each tollhouse, the soul is presented with all the sins it has committed of that kind: lying, envy, fornication, and so on. If it is found guilty of any of these sins, it is cast down to hell. If it is innocent, it is permitted to ascend.

These ideas clearly go back a long way. A nineteenth-century historian of theology, Metropolitan Macarius of Moscow, writes: “Such an uninterrupted, constant, and universal usage in the Church of the teaching of the toll-houses, especially among the teachers of the 4th century, indisputably testifies that it was handed down to them from the teachers of the preceding centuries and is founded on apostolic tradition.”

The resemblance between these ideas and those in the Poimandres is striking. One could cite other parallels, such as the seven hekhalot (palaces) of heaven mentioned in the early Kabbalah. Even the later Kabbalah often hints that the angels—including the good ones—are not necessarily the friends of man.

It would be foolish, I think, to argue that all these teachings are exactly the same, or were so in antiquity. Then as now, there was a panoply of religions and beliefs and cults, and it would be useless to try to show that their doctrines were identical. Nevertheless, the resemblances are unmistakable.

From a broader perspective, we can see the theme of man trying to situate himself in the cosmos. He looks up at the sky and sees the stars and planets and feels some connection with them. But what sort of connection? Are these entities hostile, beneficent, indifferent? And what of the unseen realms that, however dimly, each of us knows to exist?

The questions multiply. The picture of the seven planetary realms no longer fits in with astronomy, and yet one senses that it remains profoundly true. We may have to wait till death—or initiation—to find out more.

Sources

Copenhaver, Brian P. Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and an Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

“James Morgan Pryse,” Theosophy Wiki; http://theosophy.wiki/w-en/index.php?title=James_Morgan_Pryse; accessed Jan. 4, 2017.

Pryse, James Morgan. The Apocalypse Unsealed. 4th ed. Los Angeles: John M. Pryse, 1931.

Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite. The Celestial Hierarchy. http://www.esoteric.msu.edu/VolumeII/CelestialHierarchy.html; accessed Feb. 26, 2016.

Rose, Seraphim. The Soul after Death. Platina, Calif.: St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 1980.

Richard Smoley’s latest book is How God Became God: What Scholars Are Really Saying about God and the Bible. An earlier version of this article appeared in New Dawn magazine.

At the time of this writing, we have just finished the 141st annual convention of the international Theosophical Society. Again this year it was held at the headquarters in Adyar. Year after year, this event is the largest purely Theosophical gathering in the world, with over 1000 people attending. Members from around the world and from every corner of India make their plans and adjust their schedules so that they can participate. The convention lasts for five days, and during the course of the event you meet people who have a long history with the TS. It is not uncommon to encounter members who have attended every convention for the past fifty, and in some cases sixty, years. Their memories of the past and observations about the present are priceless.

At the time of this writing, we have just finished the 141st annual convention of the international Theosophical Society. Again this year it was held at the headquarters in Adyar. Year after year, this event is the largest purely Theosophical gathering in the world, with over 1000 people attending. Members from around the world and from every corner of India make their plans and adjust their schedules so that they can participate. The convention lasts for five days, and during the course of the event you meet people who have a long history with the TS. It is not uncommon to encounter members who have attended every convention for the past fifty, and in some cases sixty, years. Their memories of the past and observations about the present are priceless. On a summer day in 2014, while browsing among the bulk bins of the local food co-op, I came across a small advertising brochure that someone had abandoned. The cover showed a twenty-something white female dressed in a sheer white tunic and seated in a yogic meditation pose. Superimposed on her torso were seven colored medallions, each containing a letter of the Sanskrit alphabet. They ranged from red at her seat to purple at the crown of her head, following the order of the spectrum. Closer inspection revealed that each medallion had a different number of petal-like rays.

On a summer day in 2014, while browsing among the bulk bins of the local food co-op, I came across a small advertising brochure that someone had abandoned. The cover showed a twenty-something white female dressed in a sheer white tunic and seated in a yogic meditation pose. Superimposed on her torso were seven colored medallions, each containing a letter of the Sanskrit alphabet. They ranged from red at her seat to purple at the crown of her head, following the order of the spectrum. Closer inspection revealed that each medallion had a different number of petal-like rays.

The New Testament is probably the most widely read book in the world. And yet it is also a book that is mysterious and not fully understood. In some cases, this is because what the churches teach today no longer corresponds with what the New Testament says. This is the case with the nature and person of Jesus. (See my article, “

The New Testament is probably the most widely read book in the world. And yet it is also a book that is mysterious and not fully understood. In some cases, this is because what the churches teach today no longer corresponds with what the New Testament says. This is the case with the nature and person of Jesus. (See my article, “![Theosophical Society - The Seven Chakras Theosophical Society - A diagram from Pryse’s Apocalypse Unsealed illustrating the seven chakras along the spine, and their connections with symbols in Revelation. Pryse uses isopsephy (Greek numerology) to identify some of the key figures and symbols in the text. [*] Dionysius the Areopagite is a figure mentioned in Acts 17:34 as a contemporary of Paul. This work is attributed to him, but was very likely written 500 years later, in the sixth century CE. Hence the author, otherwise unknown, is often called “Pseudo-Dionysius.”](/files/publications/questmagazine/spring2017/The_Gnostic_Chart.jpg)