The Coming of the Sixth Sun: Mayan Views of a New Cycle

By Barbara J. Sadtler

Originally printed in the Winter 2010 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Sadtler, Barbara J. "The Coming of the Sixth Sun: Mayan Views of a New Cycle." Quest 98. 1 (Winter 2010): 14-17, 34.

As our world gets smaller and livability issues intensify, indigenous wisdom is making its way into the limelight, spearheaded by a growing awareness of the end date of the Mayan calendar in the year 2012. Ancient Mayan prophecies foretold a time when foreigners would be hungry to learn from the Maya. For more than a decade, Don Alejandro Cirilo Perez Oxlaj, also known as Wakatel Utiw or Wandering Wolf, an esteemed thirteenth-generation elder from Guatemala, has stepped into that teaching role, orally transmitting Mayan prophecies across the globe. He explains that his destiny is to be the messenger and ours is to trust him enough to listen. He talks about our planetary predicament and what we need to do to live more consciously. These teachings, the Maya say, are what we have unwittingly been waiting for.

Ironically, today average Mayans pay little attention to the year 2012. Much of their reality is shaped by abject poverty and requires them to focus on day-to-day survival. Their potentially bleak situation, however, is transformed into something magical by the eloquent languages that they use, the colorful customs the communities support, and the pervasiveness of the Mayan cosmic vision. It is Westerners who have brought their interpretation of 2012 to the Maya. Having spent time among the Maya and studying with Grandfather Cirilo Perez Oxlaj, his wife Elizabeth, and other indigenous shamans and elders, I suspect that if we Westerners venture too far out of context in interpreting their calendars, we may miss the point entirely. The true value of the Mayan calendars is found in synthesizing their wisdom into our hearts and living it moment to moment. What follows is my understanding of the Mayan perspective of time cycles and calendars, embellished with pertinent teachings from Grandfather Cirilo, all of which I hope will add discernment to the 2012 discussion.

The ancient Maya possessed an extraordinary aptitude for creating intricate and intermeshing time cycles. Time was a way of being to them, and they revered each day as a gift from the heavens. The Maya were arguably the most sophisticated timekeepers in human history, and to this day Mayans assign special "daykeepers" to track time in order to assure abundance, direction, and security.

Depending upon which scientific discipline is reporting, the Maya had from three to seventeen calendars. According to Grandfather Cirilo, the Maya kept twenty calendars for various purposes, but many were destroyed during the Spanish conquest in the sixteenth century. Because the Mayans base all of their calendars on a vigesimal system (i.e., multiples of twenty) and frequently refer to the sacred significance of the numbers twenty and thirteen (they say there are twenty digits and thirteen joints in the human body), it would make most sense to say that the Maya used twenty different but interrelated calendars.

Archaeologists commonly refer to a calendar that was shared by all Mesoamerican cultures, the haab calendar, used primarily for bookkeeping and agrarian purposes. This is a solar year system of 360 days divided into an eighteen-month, twenty-day cycle. Because the solar year is longer than 360 days, five days have been inserted between the end of one 360-day cycle and the beginning of another. This period, called the wayeb, has been synchronized with the celebrations of the Catholic Holy Week. This time also marks the change from the dry season to the rainy season. Although the wayeb is considered unlucky or hellish by some Maya, it is also a period of renewal, celebration, chaos, rituals of sacrifice, and ornate, lengthy processions that stream through the streets of Guatemalan towns and villages. By end of the wayeb on resurrection Sunday, a typical Mayan is depleted from all the celebrations, with energy remaining only for reflection and gratitude that this intensity will not happen for another year.

The Maya also use a sacred daily calendar, commonly called the tzolkin calendar, to deepen their connection to the divine nature of the universe and assist them with the inherent challenges of life. The tzolkin is a 260-day divinatory calendar that is based on the cycles of the Pleiades, the "heart of the heavens," as described in their creation story, the Popol Vuh, and in generations of elders' storytelling. In the Popol Vuh the people pledge to honor each day because each day is a deity. This is why the tzolkin calendar has been in continual use over the millennia. It does not exist in a written form, but has been passed down through generations in the oral tradition.

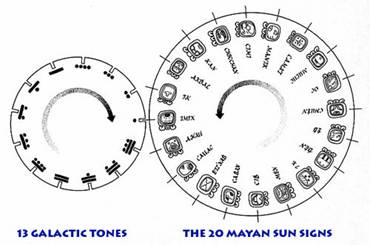

A tzolkin consists of a cycle involving twenty day signs and thirteen numbers, each of which represents a sacred, archetypal energy. Each day is signified by a glyph that represents the lord (deity) of the day in the form of plant, animal, ancestor, or force of nature. Numbers are created using a place rotation system, which combines only three symbols: eggs, dots, and lines, to represent the numerical form of the most important gods and goddesses. These are the sacred "number beings" that influence the twenty "lords of the day." Together each glyph and number creates a frequency that harmonizes with the universe. Working together like two cogged gears, the twenty day signs intermesh with the thirteen numbers, presenting a new combination each day (see figure 1).

.

|

|---|

Figure 1. A representation of the Mayan sacred tzolkin. Note the interlocking "gears" of the two calendars. Source: www.mayanmajix.com . |

Since every individual is born on one of these days, the glyph and number combination of your day of birth becomes your "day sign" (also known as "sacred sun sign"). This is the energy you carry in your heart, reflecting your intention for being in this lifetime and your soul's purpose. It is your sacred watermark of creation.

The key to using the tzolkin is to know the Mayan deities. Our chief sources for this pantheon are codices written in the Mayan hieroglyphic script. Although many of these texts were destroyed by the Spaniards, a few survive today. All Mayan deities personify some aspect of the natural world, such as childbirth, prey and predator, climate changes, elements, seasons, and time segments. These deities may be called upon to "inhabit" the body and soul at times of pivotal life experience, including rites of passage, traveling, and giving advice. Even ordinary activities such as weaving at the loom or working in the fields are believed to have greater potential when blessings from the right deity are requested.

Today there are several English versions of the tzolkin that provide easy-to-use descriptions and methods for determining your day sign. Some of these combine the tzolkin with the Gregorian calendar, enabling Westerners to consult the tzolkinon a daily basis. A ritual of morning reflection on the significance of the day's energy and setting an intention for the day's events creates an enlivened sense of purpose not found in a Gregorian Day-Timer. Use of the tzolkin brings a sacred element to each day, enabling the individual to stay present and feel gratitude for the cosmic forces that guide daily life. Many Westerners report an uncanny sense of alignment with cosmic energies and have experienced increased synchronicities and greater centeredness by using this sacred tool.

Understanding and honoring the archetypal energy intrinsic to each day can be accomplished through study, shamanic guidance, and daily meditations. Because the Mayan pantheon is both extensive and overlapping, it is important to learn what the energies are and how to correlate them to events each day. With patience, patterns emerge. Alignment with forces that foster one's greatest good becomes more tangible with practice. A daykeeper's goal is to align every activity with nature's rhythm and manage whatever comes. With practice, connection with the energies may enable one to remain in a reverent attunement with the cosmic flow.

Daykeeping becomes even more fulfilling by knowing one's sacred Mayan cross, la cruz Maya. This comprehensive system is calculated from the tzolkin and provides five additional dimensions to the heart-based day sign. The top position of the cross is the day sign on the date of your conception. The left position is energy that influences your challenges; the right, your gifts; and the bottom position reflects the energy influencing your destiny. Additionally, a year bearer day sign, brought in from the haab calendar, is included. These five glyph names, along with the name of the day sign, may be repeated together as a personal mantra. The number of spirit guides in your auric field is determined by the sum of the galactic tones (numbers) in the cross configuration. La cruz Maya may provide worthy assistance to one on a path of self-realization.

The tzolkin calendar is the focus of Mayan spirituality. Each day is auspicious for connecting with the lord of that day and asking for particular types of assistance. In fire ceremonies, shamans call upon the deities of each of the twenty days, one by one. They will do this all day long, especially on "offering" days. This elegant oratory assists in the healing of the participants, their loved ones, and the village.

The most widely known Mayan calendar, however, is known as the Long Count, and it is the source of the 2012 date. Most of the pyramids and stelae found throughout Maya country contain dates inscribed according to this calendar. The Long Count consists of thirteen baktuns, each baktun equaling 144,000 days, a cycle of 5,126 years. In the twentieth century, British anthropologist Sir J. Eric S. Thompson, in conjunction with John T. Goodman and Juan H. Martinez-Hernandez, correlated the Mayan Long Count with the Gregorian calendar. Their work, widely accepted by Western researchers, dates the beginning of the Long Count to August 11, 3114 bc. There is less agreement among Western researchers about the end date. Many peg it to December 21, 2012, but Swedish microbiologist and author Carl Johan Calleman, author of The Mayan Calendar and the Transformation of Consciousness calculates that this cycle will end on October 28, 2011. Grandfather Cirilo and other indigenous elders do not necessarily agree with these specific dates, but do believe that we are currently in the end stages of a time cycle lasting approximately 5000 years.

|

|---|

Figure 2. Cobe Stele 1. The Mayan Long Count Calendar. |

A key artifact of the Long Count calendar was discovered in Cobe, Mexico, in the 1940s. Stele 1 (figure 2) is carbon-dated to be approximately 1300 years old and has been deciphered to reveal dates trillions of years back in time. It is theorized that the Mayan Long Count calendar depicts the hierarchical nature of creation cycles, with each cycle being a multiple of 13 x 20?. This indicates that the Maya had names for time periods dating back 16.4 million years, as well as fourteen earlier unnamed cycles. Some experts believe that the named periods, appearing in the center of the stele, coincide with the evolutionary cycles described by Western science, meaning that the ancient Maya may have been aware of these cycles well before modern science.

Some contemporary research suggests that the Long Count was created by the Maya to time the evolution of consciousness. If this is true, the idea is not unique, as the Vedic yuga system has been linking time cycles with levels of collective consciousness for centuries. In the West, 2012-based theory is growing and encompasses a wide range of ideas relating to consciousness and science: philosopher Jean Gebser's complexification theory; Ken Wilber's integral theory of consciousness; microbiologist Carl Calleman's acceleration of time/creation; John Major Jenkins' precession of the equinoxes; physicist Nassim Haramein's unified field interpretations; and Gregg Braden's fractal time, to name a few.

For the Maya, the end date notation on the true Long Count calendar is 13.0.0.0.0. This dating method makes use of five different measures of time: the day (known as a kin); the twenty-day period (known as a uinal); a 360-day period (a tun); a 7200-day period, roughly equivalent to 19.7 years (a katun), and a period of 144,000 days, roughly equivalent to 394 years (a baktun.). The date 13.0.0.0.0 indicates thirteen baktuns, zero katuns, zero tuns, zero uinals, and zero kins since the beginning of the Long Count in 3114 bc. Grandfather Cirilo states that the next to last phase of this cycle, called the Vale of the Nine Hells, began about 500 years ago, with the arrival of the conquistador Hernando Cortés in Mexico in 1521 and lasted until 1987, which marked the beginning of the "Time of Warning." This was publicized worldwide as the Harmonic Convergence, introducing the Mayan end date of 2012 into Western consciousness. The Time of Warning will be upon us until the Mayan Long Count reaches 13.0.0.0.0. The next day the numbering will be reset to 0.0.0.0.0, and, it is believed, the shift of the ages will begin.

The indigenous peoples of the Americas say these shifts have happened before. Their traditions teach the existence of previous, prehistoric civilizations on our planet. As described in the Popol Vuh, the Quiché Mayan bible, the gods tried several times to create sentient beings with higher capacities. Previous peoples were made from other materials such as mud and wood, but because they did not possess or develop the capacity to worship the creator, those cycles perished. Contemporary humans, made from corn, are the most advanced version of the species to date because they know how to speak, pray, make offerings, and perform ceremonies for the gods. Each of these ages was ruled by a god of an element, such as wind, fire, or water, and was destroyed by its opposite: the world of fire, for example, was destroyed by water. Some hold that we are in the fourth world now, moving to the fifth; others state that we are entering the sixth. This may seem like mythology to Westerners, but Dennis Tedlock, an anthropologist and translator of the Popol Vuh, thinks it is more accurate to use the term "mythistory" because these beliefs are intimately woven into the reality of the Maya.

Grandfather Cirilo speaks of an extended period of darkness that will come at the end of this "sun" or world age. The prophecies foretell that the earth's second sun will pass in front of our existing sun, causing a period of darkness that will last between one and six days. He is ambiguous about the specific date for this occurrence, but indicates it may happen sometime around the Gregorian year 2012.

Clearly one of the most important elements of this teaching is the existence of a mysterious second sun that will eclipse our own and cause several days of darkness. The concept of a twin star can be found in other indigenous beliefs. The Dogon tribe of west Africa, who believe they came from the star cluster Sirius, knew, without the aid of instrumentation, that Sirius possessed two smaller stars that are invisible to the naked eye, as Robert Temple described in his celebrated book The Sirius Mystery. The Vedas refer to a similar idea. In Astrology of the Seers, Vedic scholar David Frawley writes:

We have two suns, an object that modern astronomers may call a Quasar, whose light may be obscured by dust or nebulae in the region of the galactic center. This "dark companion" appears to possess a negative magnetic field that obstructs cosmic light from the galactic center from reaching the Earth. Through this, it creates cycles of advance and decline of civilizations.

I have sought out conversations with astronomers, who agree that this is a feasible scenario given what we know about our universe. The astronomer's problem stems from the difficulty of isolating such a star and predicting whether it will eclipse our sun. As powerful as our telescopes have become, there are too many variables to determine with certainty if, how, and when such an event will occur, although thousands of astronomers worldwide, professional and amateur, are vigorously engaged in the hunt.

The elders say that at the end of the Long Count calendar a new sun, the sixth sun, is approaching. They do not specify exactly what this means. This new sun may replace our old one or continue on another path. Their legends say that this has happened before and will happen again. Herein may lay the basis for the Mayan fascination with time. If the second sun does appear around the year 2012, the Maya will gain a level of mathematical and astronomical credibility they have never before experienced, even at the peak of their civilization 1500 years ago.

Grandfather Cirilo implies that the mechanized world, dissociated from nature and the earth, will be disturbed and destroyed at some level during the hours of darkness. This, we should note, already appears to be occurring. We may be in the shift, right now, in this moment, and this process may have been taking place over a long period of time. The shift of the ages may not be a single cataclysmic event, but a series of them. In any event, it is sometimes said that the prophesied days of darkness will be an optimal time for meditation, as collectively the meditators may hold the biospheric space while the shift of the ages unfolds, helping to usher in the sixth sun and greater levels of consciousness.

For some, this shift could revive ancient wisdom and lead to peace and harmony on our planet. For others, it may not be so. Grandfather Cirilo warns that if humans do not awaken and continue to kill and pollute, a new day will not dawn. He stresses that at this time it is critical to live close to the earth and realize the connections among all of life. He is resolute about the need for unification and cultivation of respect for all humans and for nature. Being privy to these prophecies allows for adequate preparation and adjustment to sustainable, simple, and conscious living. In light of the Mayan teachings, there is ample reason to be fascinated with time, to watch the skies, and to be attentive to indigenous ways. It may be critical for our survival.

Barbara Sadtler, M.A., R.Y.T., has been studying with the Maya for several years and walks a parallel path with Tantra yoga. She teaches workshops and individual sessions to empower Westerners with the use of Mayan and yogic tools. She is actively involved in the Shift of the Ages project, Common Passion, the International Association of Yoga Therapists, and the Himalayan Institute. You can find her monthly blogs on www.maya-portal.net and http://BreatheAsYouRead.blogspot.com .

With the publication of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows in 2007, the Harry Potter cycle is now complete, so we can look at the whole story of the Boy-Who-Lived. This cycle of seven stories is undoubtedly the major fantasy work of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows sold 8.3 million copies in the United States during the first twenty-four hours after its publication. Of the first six books, 325 million copies have been sold around the globe. The books have been translated into sixty-five languages, including Hindi, Icelandic, Latin, Vietnamese, and Welsh. In one month in 2007, all seven Harry Potter books were on the list of ten best-sellers.

With the publication of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows in 2007, the Harry Potter cycle is now complete, so we can look at the whole story of the Boy-Who-Lived. This cycle of seven stories is undoubtedly the major fantasy work of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows sold 8.3 million copies in the United States during the first twenty-four hours after its publication. Of the first six books, 325 million copies have been sold around the globe. The books have been translated into sixty-five languages, including Hindi, Icelandic, Latin, Vietnamese, and Welsh. In one month in 2007, all seven Harry Potter books were on the list of ten best-sellers.