Printed in the Spring 2019 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Jeff, Rasley,"Should I Stay or Should I Go? Can a Skeptic Ever Find the Right Church?" Quest 107:2, pg 14-21

By Jeff Rasley

Should I stay or should I go?

If you say that you are mine

I’ll be here till the end of time

So you got to let me know

Should I stay or should I go?

If I go, there will be trouble

And if I stay it will be double

—The Clash

I came to the Quakers out of need, but stayed because I found something I’d lost.

I came to the Quakers out of need, but stayed because I found something I’d lost.

The first time I attended an Indianapolis First Friends worship service was at the invitation of my friend Tim Meyer. Tim was a member of a 2007 mountaineering expedition to Yala Peak that I organized. (Yala Peak is an 18,000-foot-high mountain in the Langtang region of eastern Nepal,) He was also the first contributor to a fundraising project I organized for the village school in Basa, Nepal.

Niru Rai is the owner of Adventure GeoTreks, the outfitter company I have partnered with on Himalayan expeditions since 2006. He employs guides, cooks, and porters from his home village, Basa. During the 2006 expedition, our guide, Ganesh Rai, told me the school in Basa had only three grades, and the village wanted to add fourth and fifth grades. Back in Katmandu, Niru asked whether I would be willing to raise $5000, which would pay for the materials needed to add two classrooms and would pay the salaries of fifth- and fourth-grade teachers for three years. Villagers could provide the labor to build the addition to the school, and the government would pay the teachers’ salaries after three years.

Wow, what a bargain! Five thousand dollars was all it would take to provide kids in Basa with two more years of education.

Fundraising to expand the school was so successful that Niru and I decided we should work together on other projects for Basa.

I visited the village in 2008. It didn’t have electricity, water, or toilets. No road reached the village; there were no vehicles, not even a bicycle. I learned that the villagers wanted electricity so they could have light after dark from sources other than their cooking-fire pits.

Niru, Mike Miller, a friend and electrical engineer, and I worked out a budget and determined that the cost of all the parts and materials required to build a little hydroelectric plant on the stream that supplied water for the village was only $22,000. The villagers could supply the necessary labor.

We needed a tax-exempt organization through which contributions could be funneled so donors could claim a charitable tax-deduction. A Presbyterian church I had belonged to had supported previous fundraising projects. But I’d parted ways with the Presbyterian church.

That’s when Tim Meyer suggested I come with him to meeting at Indianapolis First Friends. (Quakers call their worship services “meetings,” and they refer to the congregation as “the Meeting” and to the place of worship as a “meeting house.”) Tim’s plan was to introduce me to the Meeting and then ask First Friends to be the sponsor (“fiscal agent” in IRS lingo) of the fundraising project.

The plan worked. I was invited to speak at the monthly meeting for business at First Friends. A resolution was approved that the Meeting would act as fiscal agent for the Basa Village hydroelectric project.

The Meeting continued to support infrastructure development in Basa even after the Basa Village Foundation (BVF) became a separate tax-exempt corporation. The BVF has fund-raised and worked with Niru and the village to build a water system and a new school and provide smokeless stoves, temporary medical clinics, school uniforms, coats and shoes, solar-powered LED lights, computers, and books for the school. The BVF also contributed funds to rebuild the village after earthquakes in 2015, and has plans for future projects in other remote villages.

Tim’s fortuitous invitation was the pebble dropped into the pond that rippled out to connect Quaker Friends in Indianapolis with my Rai friends in Basa. (Most of the villagers in Basa belong to the Rai ethnotribal group of eastern Nepal.)

The willingness to help and my first experience of a Quaker service at First Friends led me to think Tim’s introduction could satisfy another need. A couple years earlier I’d left the Presbyterian church of my forefathers and mothers. I had been church shopping since then.

The welcome I received at First Friends on my first visit was not nearly as boisterous or moving as the one I received in Basa on my first visit to the village. The Quakers did not greet me with flutes and drums. I wasn’t showered with flowers, and there wasn’t any dancing and singing. I did receive a few hugs and friendly handshakes after the worship service, along with tea and cookies. I wasn’t overwhelmed with hospitality as I was in Basa, where every family wanted my fellow trekkers and me to visit their homes and sample their homemade brew and a plate of rice.

What really made an impression on me at the first Quaker service I attended was what they called “unprogrammed worship.” During the service there were hymns, choir and organ music, and a sermon—all the familiar elements of a mainline Protestant service. The new twist was fifteen minutes of the unique form of traditional Quaker worship. (We had moments of silence in Presbyterian services, but the moment was over as soon as you bowed your head.)

Pastor Stan explained that the spirit of God is in all of us and that, if the spirit led anyone to speak, they should do so. Otherwise, we should center down in silence and wait upon the spirit. When the quiet time began, it felt like a hundred pairs of lungs were breathing together. In that silence I felt the awesomeness of the universe and gratitude to be alive in it. The feeling was similar to experiences I’d had in Nepal in Hindu puja (worship) ceremonies, Buddhist mantra chanting, and Rai dancing. It was a thoughtfully pragmatic worship experience. It allowed busy people living in urban America time to relax and meditate. It also allowed the opportunity for anyone who felt so led to speak from their heart.

So I went to the Sunday meeting the next week, and the week after that, and the week after that. The openness to diverse views, sincerity in worship, a communal method of decision making, and an emphasis on positive values rather than doctrinal beliefs at First Friends fit my conception of how a worship community ought to be.

Four generations of my family had sat in our pew at First Presbyterian Church of Goshen, Indiana. But I left the denomination of my heritage because the structural and doctrinal rigidity of Presbyterianism no longer worked for me. My evolving attitude toward religion was influenced by experiences in Nepal and India, where I had been trekking, climbing, and engaged in philanthropic projects since 1995. The animistic, nature-worshipping Rai people had especially influenced my theology.

Such lofty considerations hadn’t enticed me to sample First Friends. I just wanted to find a sponsor for fundraising projects in Basa. Finding a community that synced with my idea of what a church ought to be was serendipity. After attending First Friends for eighteen months, I became a pledging member in 2011.

Last year, I resigned my membership.

The Basa Rai do not have a formal religion, regular religious services, or a written language. They tell stories about gods and spirits in their native language, and they celebrate weddings, births, and Hindu and Buddhist festivals. Each time I lead a trekking group to Basa, we are showered with flowers. There is lots of singing, dancing, drinking, and eating. Without the distractions of TV, radio, telephones, and vehicles, the subsistence-farmer villagers delight in any excuse to party.

The village shaman performs healing and other ceremonies, but Western medicine is also respected. The Basa Rai have lived their traditional way of life for hundreds of years. Fundamental to that way of life is sensitivity to other people and to nature.

Once when I was walking with Ganesh Rai, I started to kick a rock out of the middle of the trail. He gently gripped my shoulder, stepped in front of me, and moved the rock out of our way. He explained that the rock’s spirit should be respected.

Below the high mountain passes, trekking through rainforests or jungles with Ganesh and other guides from Basa is a lesson in botany and biology. They name all the flora and fauna we encounter and describe both the medicinal and the dangerous characteristics of plants and trees. The village depends on wood burning for heat and cooking, but they do not kill trees. Sticks are gathered and branches can be cut, but a tree won’t be chopped down unless it is dead.

The Basa Rai grow what they eat. They will only eat meat if the animal is dying. They live a simple and beautiful way of life, with family and communal relationships at the center. Visitors to the village are rare, but strangers are welcomed as guests.

In Basa and throughout Nepal we greet each other with “Namaste,” which serves as “Hello” but also has a spiritual connotation of “I recognize god in you.” So I recognized a certain amount of congruence between the animistic spirituality of my Rai friends and the Quaker understanding of God in all of us.

My own view is that some form of energy (maybe the vibrations of string theory, or whatever) is animating our universe and everything in it. Scientists studying cosmogony and cosmology are discovering more information and developing deeper understandings of the properties that govern the universe. Imagining and theorizing is fun and creative, but it’s not Truth.

Theological propositions may seem logical when the premises of the particular religion are accepted. But what is the real purpose of constructing an imaginary system, claiming it is Truth, and demanding that others believe it? I don’t think the purpose is benign. I do think we are better off admitting our ignorance and remaining agnostic about what we don’t actually know.

The story-myths of the Rai are about supernatural spirits. They are told differently by different storytellers. The Rai don’t have religious doctrines or exclusive practices, so they have happily incorporated Hindu and Buddhist festivals into their calendar. A Christian church was built in Basa because Tek, one of the village elders, learned about Christianity and decided he would like to be a preacher. Tek doesn’t have a Bible, but occasionally a few families gather in the church to sing and hear Tek talk about Jesus.

Religion at its best is imaginatively creative, tolerant, and inclusive. Religion at its worst claims it alone has the answers to unanswerable questions and condemns or scorns those who disagree.

One reason I left the Presbyterian church is that Calvinist theology is cruel and ridiculous. It says that before the beginning of time, in his infinite wisdom God decided the ultimate fate of every human—who goes to heaven and who to hell: double predestination.

But I still wanted to participate in a community of people who gather together to share in the awe and gratitude I feel for the existence of our world, to talk about it, sing about it, contemplate it, and break bread together. I could travel halfway around the world and trek over 10,000-foot-high passes to experience all of that in Basa; but in Indianapolis?

Thanks to Tim, I discovered that I could drive five minutes from my house to experience that at Indianapolis First Friends. There it seemed my desire to participate with others in experiences that express awe and wonder at the beauty and mystery of existence, without ceding rationality to superstition or rigid orthodoxy, could be fulfilled.

I soon learned that many members of First Friends, and many Quakers, believe in Christian superstitions and irrational beliefs. Pastor Stan made it clear, however, that his and any other Quaker’s beliefs were theirs alone and not the official position of First Friends or the Society of Friends (the Quaker denomination).

The successor to Stan was Pastor Ruthie. She is a trained opera singer and has a voice that can send a sinner to heaven. She has a warm and sweet personality. Unlike Pastor Stan, her Sunday messages were expressly evangelical Christian. Almost every Sunday she said things in her sermon that are at odds with my animistic agnosticism.

Ruthie describes God as actively intervening in human affairs. An example that felt like fingernails on a chalkboard to me was “God can heal your ouchies.” Ruthie was talking to kids in vacation Bible school about “what God can do for you.” A god who would respond to a child’s prayer to heal her scraped knee while allowing other children to be molested, murdered, and starved, is no god I can worship. It troubled me that the next generation of Quakers is being indoctrinated into a theology similar to the one I grew up with and that took so long to deprogram myself of.

Although she knew that I do not share her beliefs, Ruthie asked me to lead a weekly discussion group prior to Sunday worship. I led the class for several years. I was also asked to deliver the message in worship a few times during both Stan’s and Ruthie’s tenures. My theology or lack thereof was not a bar to becoming a voice within the Meeting. (My book, Godless: Living a Valuable Life beyond Beliefs, was promoted in the First Friends newsletter and reviewed in the national publication, Friends Journal.)

Toleration of difference is a fundamental value of First Friends. In the adult discussion group I led (“The Wired Word Coffee Circle”), Duffy, a self-described evangelical Christian, was a regular participant. Howard was a self-described atheist. The other regular attendees covered the theological spectrum between those polar positions. Another regular, Daoud, is Muslim. Every week we engaged in passionate discussions and disagreements, then went to worship together. The acceptance of difference, disagreement, and diversity kept me coming back to spend Sunday mornings at First Friends.

Not all Quaker Meetings are as tolerant as First Friends. Conservatives in the Western Yearly Meeting (a regional Quaker organization) tried, but failed, to unrecord (meaning defrock) a well-known pastor-author, Phil Gulley. Gulley had openly preached and written about universalist theology. He claimed that the Christian way is not the only way to understand God. Several conservative Meetings withdrew from Western Yearly Meeting after the bid to unrecord Pastor Gulley pooped out. In 2012 the Indiana Yearly Meeting expelled the West Richmond Meeting for openly welcoming gays and lesbians.

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015 guaranteed the constitutional right to same-sex marriage. At this point, during Ruthie’s tenure, First Friends undertook a series of meetings and discussions to discern whether the Meeting should perform same-sex marriages. There was overwhelming support for performing same-sex weddings in the meeting house. But two members left because they were upset about how slow the process of discernment was moving and that the Meeting did not express public support for the right to same-sex marriage. On the other hand, at least three members left because they could not abide the Meeting’s violating the biblical injunction against homosexuality.

The issue was finally resolved at a monthly meeting for business after months of discussion. Because no one stood in the way and refused to accept the proposal, a policy of allowing same-sex marriage of members was approved.

My initial enthusiasm for Quakerism was tempered by observing internal squabbles and by Pastor Ruthie’s anthropomorphic conception of God. But where else in Indianapolis could I find a worshipping community that tolerated my animistic agnosticism?

The founder of the Friends movement, George Fox, in seventeenth-century England proclaimed that it was revealed to him through study of the Bible and revelation that God is in all people. Early Quakers developed a communal way of decision making, which requires consensus to the extent that no member “stands in the way.”

I’ve witnessed decision making in the Basa village, and it works very much like the Quaker way. Everyone in the village gathers by the school, and they talk until a consensus is reached. The meeting about how to build and operate the hydroelectric system lasted the better part of two days. The outcome was a plan in which every villager had a role from serving food to stringing wire up a sheer 100-foot-high cliff to operating the completed generator.

The Quaker concept of God, coupled with a tradition of holding no doctrines and consensus decision making, seemed as close as I would come to finding a worship community that could tolerate me and that I could tolerate.

I did not want to get sucked into ecclesiastical disputes or the minutiae of administering a church, so I never went to a Yearly Meeting and kept a distance from the internal politics of First Friends. I had rejected the doctrinal baggage of Christianity, but I still felt a visceral pull to be connected to a church. I was programmed to get up Sunday morning and go to church.

The spiritual hymn

Lord, I want to be a Christian

in my heart, in my heart.

Lord, I want to be a Christian in my heart.

In my heart, in my heart . . .

was embedded deep in my psyche.

I could tolerate anthropomorphic theology to feed my need so long as I wasn’t forced to return to the status of stealth worshipper, as I had been in the Presbyterian church.

I’ve known numerous members of Christian congregations who are stealth worshippers. They don’t agree with their denomination’s doctrines, but they continue to find meaning in the community of their church. Stealth worshippers enjoy worship services, communal sharing, and other activities, while secretly rejecting “truths” claimed by their church.

I have given talks and sermons for a number of diverse churches in Indianapolis and Chicago and have heard the “confessions” of stealth worshippers. Many of them are convinced that they need to keep their disbelief to themselves or share it only with trusted friends.

At one point I was a candidate for ordained ministry in the Presbyterian church. An elder of my church, knowing that the candidates committee was going to examine me about my beliefs, asked me what I would say when questioned about the resurrection of Jesus. Bill sidled up beside me during the coffee klatsch after services, darted guarded looks in all directions, and then whispered his question. Bill admitted that he didn’t believe in the resurrection and wondered how a rational fellow like me was going to duck The Question. He assumed I did not believe in Christian myths like the virgin birth and resurrection, but to hold leadership positions within the Presbyterian denomination, one had to pretend to believe.

Because I went to seminary, I came to know quite a few Christian ministers. As an attorney, I represented several churches and ministers in legal matters. Several Protestant ministers and two Catholic priests came clean with me about their disbeliefs. I discovered that when they were not “on,” many pastors shared my agnosticism.

As a candidate for the ministry, I was counseled by other Presbyterian ministers to “just tell them what they want to hear” in order to pass the examinations about my beliefs. I was covaledictorian of my seminary class, won awards for accomplishments in ancient Greek and Hebrew, and was “highly recommended” by the psychologist who performed personality tests for our presbytery. But I was forced to part ways with the Presbyterian church.

During my oral examination, a committee member exclaimed, “Why, you seem more like a Buddhist than a Calvinist!” What un-Calvinistic blasphemies might be unleashed had I led a congregation in chanting Om mani padme hum instead of the Apostles’ Creed?

The candidates committee decreed that I should go through Calvinist reform school if I wanted to proceed as a candidate for ordained ministry. I demurred.

At First Friends, there was no need for stealth. Howard, the atheist, Duffy, the evangelical fundamentalist, and Daoud, the Muslim, were all active and popular members of the Meeting.

I haven’t agreed with some of what is spoken or prayed under the roof of First Friends, but I’ve never felt forced to mouth words I do not believe, as I did every Sunday in Presbyterian services when we recited the Apostles’ Creed. The version we recited is a litany of statements which, by the time I was an adult, I thought absurd, irrational, or mythological.

Services that include the elements of traditional Christian worship—hymns, chants, incense, candles, prayers, sermons, meditative silences, confessions, and after-service coffee—but not declarations of faith can comfortably include skeptics. Most churches claim to welcome everyone, but they only admit into membership those who swear to a set of orthodox beliefs. Instead of welcoming all, Christian doctrines divide and separate.

When religious services are stripped of divisive truth claims, skeptics, agnostics, and atheists can participate unstealthfully. Why not truly welcome everyone into the community so that anyone can enjoy all that is good about religion—the music, meditation, hearing a good message, supporting just causes, and drinking coffee after services?

First Friends has stripped worship services of any overt affirmation of Christian doctrine. But as time went on, I regularly found myself sitting at the back of the sanctuary wishing it would take the next step: to cease and desist making statements about a god that does not exist.

But to try to impose my animistic agnosticism on the Meeting would be to commit the same sin of doctrinal intolerance that had driven me from the Presbyterian church. So why did I commit that sin?

After Pastor Ruthie resigned, a pastoral search committee (PSC) was formed to replace her. I offered to serve on the PSC. I intended to try to influence the committee to find a pastor like Phil Gulley, who would advocate universalism.

I was not chosen by the nominating committee to serve on the PSC. I was informed I could serve as an alternate, which meant I should attend the committee meetings but would not participate in the hiring decision.

I interpreted this message from the inner circle of First Friends to mean that there is a limit to the commitment to toleration and progressive theology, and that I was outside the limits for influencing leadership of the Meeting.

So should I stay or should I go?

Biology teaches that every living creature on earth descends from the same original first cell. Astrophysicists and my Rai friends claim that everything in our universe is connected, as it all comes from the same original source. So it makes a certain sense to say that everything in the world has spirit.

Regardless of what one imagines about reality beyond rational proof, surely we can all agree that it is good that our world exists and (unless one is suffering unbearable pain) that to be alive in it is good. It is good to share gladness and sadness with others. Why must religions make it any more complicated than that?

Some Christian friends that have trekked with me in Nepal find it amusing that local Hindus believe praying to the god Ganesh will bring success in business. Ganesh’s father, Shiva, cut off his son’s head and replaced it with an elephant’s. Ganesh’s usual mode of transportation is to ride a mouse. How successful can that guy with the big ears and trunk riding a mouse be at securing a business deal?

At the same time, many Christians believe the walls of Jericho fell down because the Ark of the Covenant was paraded around for seven days. They believe that Saul and his companions were blinded by a light on the Damascus road but that only Saul heard the voice of Jesus. Hallucinations are a symptom of schizophrenia, so maybe Christians ought to restrain their derision of the beliefs of other religions.

Why not admit our ignorance of the answers to questions like how the universe was created? Why not accept that an afterlife in heaven or hell defies experience and logic? The religious response of awe and gratitude is the creative source of beautiful art, literature, cathedral architecture, the canticles of St. Francis, and the meditations of Thich Nhat Hanh. The schismatic and doctrinal demands of authoritarian religious (and political) regimes have the opposite effect. They divide and conquer.

I came to the Quakers at First Friends with an ulterior motive. Instead of turning me away, the Meeting responded like the Good Samaritan. By treating me as a friend in need, Hoosier Quakers extended a helping hand halfway around the world.

But this year I thought I might finally be ready to cut the cord with religious organizations. Then I discovered All Souls Unitarian Church about fifteen minutes from my house. I was asked to deliver the message at an All Souls service this summer. The Unitarians I met were very friendly and the church gave half the offering collected that Sunday to the Basa Village Foundation. During the service and lunch afterward I did not once experience fingers on a chalkboard or hear talk of God healing anyone’s ouchies.

Should I stay or should I go?

Jeff Rasley is the author of ten books; the most recent is Island Adventures: Disconnecting in the Caribbean and South Pacific. He has published numerous articles in academic and mainstream periodicals. He is an award-winning photographer, and his pictures taken in the Himalayas and Caribbean and Pacific islands have been published in several journals. He is the founder of the Basa Village Foundation, which raises money for culturally sensitive development in the Basa area of Nepal. He currently serves as a director of five other nonprofit organizations.

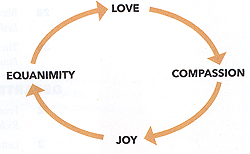

Christianity and Buddhism both speak of love and compassion, although in different proportions.

Christianity and Buddhism both speak of love and compassion, although in different proportions.

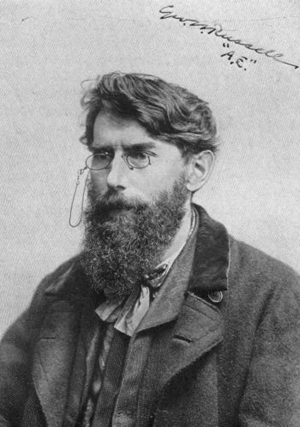

The masterfully told stories of a magical nanny that held adults and children alike spellbound for decades might incline readers to think that Australian author Pamela (P.L.) Travers merely had an overactive imagination. The truth is that her talent blossomed out of a fertile garden of occult teachings and paranormal experiences, nurtured and inspired by some exceptionally gifted personalities in real life. The movie Saving Mr. Banks and the documentary The Real Mary Poppins have treated the public to insights on her relationship with her father, the influence of the aunt she called Sass, and her tumultuous association with Walt Disney. Of equal gravity was her lifelong attraction to mystical pursuits and the guidance of the philosopher and mystic G.I. Gurdjieff.

The masterfully told stories of a magical nanny that held adults and children alike spellbound for decades might incline readers to think that Australian author Pamela (P.L.) Travers merely had an overactive imagination. The truth is that her talent blossomed out of a fertile garden of occult teachings and paranormal experiences, nurtured and inspired by some exceptionally gifted personalities in real life. The movie Saving Mr. Banks and the documentary The Real Mary Poppins have treated the public to insights on her relationship with her father, the influence of the aunt she called Sass, and her tumultuous association with Walt Disney. Of equal gravity was her lifelong attraction to mystical pursuits and the guidance of the philosopher and mystic G.I. Gurdjieff.

H.P. Blavatsky (1831–91), HPB, as we call her, is the one of the few nineteenth-century esoteric authors widely remembered today. She is, of course known to Theosophical Society members, but not always read by them. Only in recent decades have her (almost) complete works become widely available. Some of her essays and reviews were long out of print until included in the Collected Writings, edited by Boris de Zirkoff and published between 1966 and 1991. The standard edition of her letters is still in progress. There are varying versions of her Esoteric Instructions.

H.P. Blavatsky (1831–91), HPB, as we call her, is the one of the few nineteenth-century esoteric authors widely remembered today. She is, of course known to Theosophical Society members, but not always read by them. Only in recent decades have her (almost) complete works become widely available. Some of her essays and reviews were long out of print until included in the Collected Writings, edited by Boris de Zirkoff and published between 1966 and 1991. The standard edition of her letters is still in progress. There are varying versions of her Esoteric Instructions. Theosophy, while not a religion but a search for truth, draws heavily from Buddhist insights. Buddhism, like Theosophy and most religions, is a system of teachings aiming to assist its adherents to attain spiritual enlightenment. The underlying idea is that as we cultivate our awareness and awaken spiritually, we naturally help to bring healing and harmony not just to ourselves, but also to our society.

Theosophy, while not a religion but a search for truth, draws heavily from Buddhist insights. Buddhism, like Theosophy and most religions, is a system of teachings aiming to assist its adherents to attain spiritual enlightenment. The underlying idea is that as we cultivate our awareness and awaken spiritually, we naturally help to bring healing and harmony not just to ourselves, but also to our society. I came to the Quakers out of need, but stayed because I found something I’d lost.

I came to the Quakers out of need, but stayed because I found something I’d lost.