Printed in the Spring 2024 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Grasse, Ray "Toward a Grand Unified Theory of Synchronicity" Quest 112:2, pg 20-25

By Ray Grasse

This paper is the culmination of a decades-long process of investigation into Carl Jung’s theory of synchronicity, which first began with the writing and publication of my book The Waking Dream in 1996. That’s where I first hinted at the possibility of a broader metatheory that might help us better understand the significance of “meaningful coincidence,” not only as it occurs within our own lives but in the world at large. This essay lays out a tentative framework for that approach.

Symbolist thinking regards the world as a kind of language, with the people, animals, and events representing elements of a living vocabulary.

—The Waking Dream

In 1952, psychologist Carl Jung published his seminal work Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle on a phenomenon he termed synchronicity, which can be simply defined as the experience of “meaningful coincidence,” as Jung put it. While most coincidences in our lives can be easily explained as nothing more than the result of pure chance, some coincidences are so striking that we’re compelled to wonder if there isn’t some deeper purpose or process at work underlying those events.

In 1952, psychologist Carl Jung published his seminal work Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle on a phenomenon he termed synchronicity, which can be simply defined as the experience of “meaningful coincidence,” as Jung put it. While most coincidences in our lives can be easily explained as nothing more than the result of pure chance, some coincidences are so striking that we’re compelled to wonder if there isn’t some deeper purpose or process at work underlying those events.

A famous example from Jung’s own files was that of the patient who described a dream she had involving an Egyptian scarab beetle. She’d been resistant in her therapy up to that point and firmly entrenched in a rigidly rationalistic mindset towards life. While listening to her describe that dream, Jung heard a tapping at the window of the therapy room. It turned out to be from a beetle—the closest approximation to a scarab in those northern Swiss latitudes. Taking this as a cue, he went and grabbed the beetle from the window and handed it to her, saying, “Here is your scarab.” The fact that this occurred at a key moment in the woman’s therapy struck Jung as significant, and her receiving it seemed to trigger a breakthrough in her rationalistic mindset.

Jung regarded experiences like these as eruptions of meaning—that is, significant events in our psychological or spiritual growth, issuing from that mysterious divide between our inner and outer worlds. Importantly, the appearance of the beetle wasn’t “causal”—that is, it didn’t happen directly because of anything either the woman or Jung said; rather, it arose simultaneously through a deeper connectedness of meaning. This was an example of what Jung called acausal connectedness.

Since its publication, Jung’s theory has spawned a virtual tsunami of books, articles, and media discussions, all attempting to understand its nature and importance. So how best shall we grasp what meaningful coincidence really says about our world?

In Search of the Big Picture

I’d like to propose the possibility of a grand unified theory which aims to place synchronicity into its broader context. Just as some scientists have been searching for a unifying model that ties together the disparate forces of nature, so we can envision a theoretical framework that not only reveals fundamental insights into synchronicity’s workings but illumines its connection to various other concepts and symbolic systems. As we’ll see, this necessarily requires a more philosophical approach than a scientific one, as only the former can truly unravel the deeper mysteries of this phenomenon. By focusing our attention merely on isolated coincidences, I believe we run the risk of missing the true significance—and magnitude—of the synchronistic phenomenon.

As an analogy, I’d invite you to recall the classic tale of the five blind men and the elephant. Each of them examines a different part of this creature’s body, as a result obtaining a completely different sense of what the animal is like. For instance, the man feeling only the elephant’s tail naturally concludes that this creature is similar to a snake or perhaps a length of rope; but he obviously has a woefully incomplete picture of what the whole elephant is like. Because his perspective is so narrow, he misses the full reality.

I’d suggest that trying to understand synchronicity solely by focusing on isolated coincidences is akin to the predicament of the blind man who examines only one part of the elephant. By limiting our focus strictly on individual instances of synchronicity, we’re missing the broader worldview of which coincidences are just a part.

In short, understanding the true significance of synchronicity requires nothing less than a dramatically different cosmology than we are generally familiar with in our modern materialistic culture.

But what exactly is that “dramatically different cosmology”?

The Symbolist Worldview

This is what I (and certain other colleagues, like John Anthony West) have called the “symbolist” worldview. This way of thinking regards the cosmos as akin to a great dream—and, like our own dreams, written in the language of symbols. “The symbolist standpoint considers life to be a living book of symbols, a sacred text that can be decoded” (Grasse, 6). The manifest world mirrors an underlying consciousness, much in the same way that our nightly dreams reflect the workings of our own consciousness, but on a vastly different scale. The world is not only suffused with mind, it’s saturated with meaning. In The Waking Dream, I boiled down the symbolist worldview to a few essential points, including these:

- The world reflects the presence of a greater regulating intelligence, or Divine Mind, which both permeates and transcends material reality.

- All things partake in a greater continuum of order and design; consequently, there are no coincidences or truly random events. In turn, any seemingly chance event or process can divulge greater patterns of meaningfulness within the life of an individual or society.

- Reality is multileveled in character, involving phenomena and experiences across a wide range of frequencies or vibrations.

- The world is interwoven in a complex web of subtle correspondences: secret connections that link seemingly diverse phenomena through a deeper resonance of meaning.

- All phenomena can be reduced to a basic set of universal principles or archetypes. Described in various ways by different traditions, these principles constitute the underlying language of both outer and inner experience.

While all of those points play an important role in a broader metaframework of synchronicity, I’d like to focus our attention here on one of those in particular—the doctrine of correspondences.

The Doctrine of Correspondences

Virtually every esoteric or magical tradition has subscribed to this concept in one form or another, which can be broadly described as a sense that all things are connected in ways beyond the immediately obvious, involving a subterranean network of deeper qualities or metaphoric essences. As Ralph Waldo Emerson put it in his essay “Demonology,” “Secret analogies tie together the remotest parts of Nature, as the atmosphere of a summer morning is filled with innumerable gossamer threads running in every direction, revealed by the beams of the rising sun” (Emerson, 2:949).

For instance, suppose you were to ask a scientist to explain what the planet Mars really is. They would likely fall back on describing it in terms of that planet’s most obvious and observable properties—its chemical or elemental composition, its physical dimensions, weather patterns and energy fields, cosmic history, orbital dynamics, and so on. Furthermore, were the scientist to try and classify it in relation to all other phenomena in the universe, they would likely think in terms of readily observable relationships, such as the fact Mars belongs to a particular class of celestial bodies and interacts with those bodies in measurable ways that include gravity, magnetism, and so on. Simply put, the scientific perspective would provide us with a quantitative approach toward understanding the planet Mars.

But for the symbolically minded student, Mars can also be understood in terms of its essential qualities or symbolic meanings—a perspective that requires a very different mode of perception, and one that affords access to a very different order of information within the universe’s phenomena.

Seen through a more symbolic lens, Mars can be linked to such qualities as force, energy, or assertiveness. These, in turn, link through a subtle network of qualities to other phenomena such as warfare, the metal iron, anger, energy, sharp objects, fire, and still others. From this perspective, a certain event might happen over here, just as the planet Mars is engaged in a planetary dance over there, and though the two may not seem connected in any obvious way, they can be related through subtle tendrils of meaning, through subtle patterns of archetypal resonance. While the purely literal-minded eye would regard such meanings and connections as nonsensical and entirely imaginary, to the esoteric eye they are quite real, albeit subtle.

This mode of thinking regards the world as consisting of verbs and living processes, rather than solely as nouns or things. Indeed, all phenomena can be viewed on either of these two levels—literal or symbolic, as nouns or as verbs. Each level has its own validity and relevance, but it’s on this more symbolic level that we uncover that otherwise hidden network of acausal connections that links all phenomenon in our lives, and in turn to the cosmos.

When seen on that subtler level, we discover that our lives are permeated with coincidences of one sort or another, although some are more obvious than others. As such, the rare and dramatic “meaningful coincidence” described by Jung is only the tip of a far greater iceberg of interconnectedness that spans our entire lives.

Jung hinted at this himself when he spoke of the individual synchronicity as just “a particular instance of general acausal orderedness,” yet in the end, he chose to narrow his focus almost exclusively on the rare and unusual coincidence. Why? Presumably to make an already difficult subject less difficult and more digestible to both colleagues and general readers.

Whatever his reasoning, the key toward embracing that broader vision of synchronicity lies within a cognitive or epistemological shift. Seen through a purely literal-minded eye, synchronicity indeed appears to be a rare and infrequent phenomenon; but when perceived through the eye of metaphor, one’s vision opens up to a far broader universe of meanings and acausal connections, similar to how donning a pair of night vision goggles allows someone to behold a previously hidden landscape of subtle patterns not visible before.

Astrology: The Celestial Skeleton Key

Admittedly a controversial inclusion to the discussion, astrology is a subject even Jung himself felt important to include in this study. He believed that the correlation of planetary movements to an individual’s life experience provided a real-world illustration of synchronicity in action. As an example, he found that an analysis of certain sun and moon configurations between married couples offered statistical evidence for the presence of a synchronistic connection between heavenly patterns and personal experience.

While I largely agree with Jung’s view, my own reasons for including it here are somewhat different, and broader. Because astrology essentially represents the art and science of correspondences, it provides an especially helpful tool for approaching that otherwise hidden network of meanings we’re discussing here.

Because of its elaborate network of symbolic “rulerships,” whereby each planet or zodiacal sign is assigned a host of subtle connections throughout the world, one quickly discovers that our lives are populated by countless acausal associations that are otherwise invisible to the purely physical eye. One value of astrology is that it gives us the ability to examine those subtle connections more quickly, and far more comprehensively. Let me give a simple example.

Suppose someone finds themselves in the midst of a disruptive period in life where no obvious synchronicities or coincidences seem visible. Apply the lens of astrological symbolism to their life, however, and you may well discover that the planet Uranus is firing strongly in their horoscope right then—at which point a host of acausal connections and subtle coincidences suddenly become clear, all related to the overarching principle of “Uranus.” This might include such Uranian correspondences and symbols as technical or mechanical problems, delays in catching a flight, issues of personal freedom in a relationship, or even an injury to the ankle (the body part associated with Uranus). Yet this particular matrix of secret analogies would be completely invisible to the strict materialist, since it requires a heightened sensitivity to metaphoric essences rather than purely obvious appearances.

In that way, astrology provides us with an especially useful tool for helping us become more familiar with this subtle language of correspondences and, in turn, the deeply synchronistic language of daily life.

Envisioning a More Holistic Model

So where do we go from here? Picking up from where I left off in The Waking Dream, I’d suggest a few possible directions for continued research and exploration.

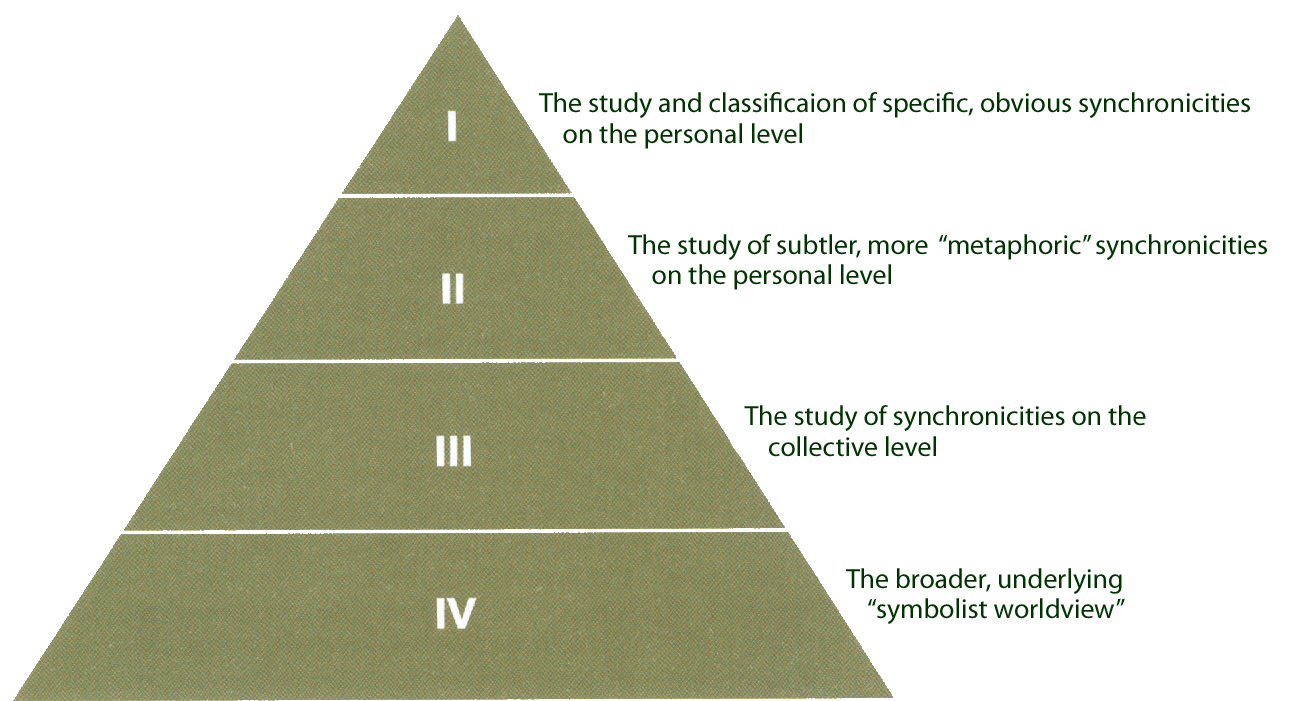

A more holistic and integral approach to synchronicity might be envisioned in the form of a pyramid, with the narrowest aspects of this research symbolized by the pyramid’s peak and expanding downward to include progressively broader aspects of synchronicity closer to the bottom, as follows:

|

| A Prospective Model for a "Unified Field" Approach to the Study of Synchronicity |

I. At the peak of the pyramid, akin to the most visible portion of an iceberg, a systematic approach to synchronicity would focus on the study and classification of meaningful coincidences of the most obvious and literal types—such as a woman talking about her dream of a beetle at the precise moment one appears at the window.

II. At the next level down, our focus would broaden out to include meaningful coincidences of a more symbolic and subtle nature, where the emphasis is less on the form of the event and more on the underlying meaning. A simple example of that would be the time I was biking over a footbridge in a local forest preserve and unexpectedly saw a deer swimming across a river, something I’d never seen before in all my years of hiking or biking. I later discovered that this sighting occurred at the very moment a close friend of mine passed away following a lingering illness. (In fact, I’d even been thinking about that friend just moments before encountering the deer.) Strictly on its surface, there is no obvious coincidence between a deer crossing a river and news of someone’s death; yet to someone employing an analogical or metaphoric eye, the synchronistic connection is clear enough, and even echoes back to classical notions likening death to the crossing of a river. At this level of our pyramid, we could also include the wide range of symbolic messages described in various divinational traditions such as pyromancy, cledonism (divination based on chance remarks), ornithomancy, geomancy, bibliomancy, and many others—all of which involve meaningful or anomalous events and connections but which may not take the form of obvious, readily recognizable coincidences.

III. Moving further down the pyramid, our study widens out to focus on more collective synchronicities and symbolic events, both obvious and subtle, involving groups of people rather than solitary individuals. One example of this would be the outbreak of revolutionary fervor that sometimes occurs across the world in seemingly unrelated contexts at the same time. In his book Cosmos and Psyche, my colleague Richard Tarnas points out how the famed mutiny that took place on the English ship H.M.S. Bounty in 1789 happened at the same time as the French Revolution—two historic events involving rebellious uprisings, yet without any direct connection between the two (Tarnas, 50‒60). In turn, Tarnas notes, this took place during a powerful astrological aspect between the planets Uranus and Pluto. This could obviously be considered a synchronicity, yet it affected far more than one lone individual.

IV. At the base of the pyramid we find the study of the synchronistic worldview at its broadest—that is, what is the symbolist cosmology underlying all these levels? This level of inquiry would include such topics as the doctrine of correspondences, the law of cycles, the nature of archetypes, and even the doctrines of karma, reincarnation, and teleology (purpose) in relation to the more personal side of this phenomenon. These are all interconnected elements informing the unfoldment of meaning on the personal, collective, and universal levels.

Last but not least, a truly integral approach to synchronicity would involve a deeper look into the potential theological dimensions of this phenomenon—is the universe the dreamlike expression of a great being or some cosmic principle? That’s not a possibility we should overlook too casually. In order for the diverse events of our lives to be interwoven as intricately and artfully as synchronicity implies, and as systems like astrology empirically demonstrate, there would seem to be a regulating intelligence underlying our world, a central principle organizing all of its elements, like notes in a grand symphony of meaning.

Revisioning Jung’s Synchronicity

To recap, I’ve suggested that the phenomenon of synchronicity can be best understood in the framework of a cosmology that regards the entire world as dreamlike in nature, and which is as symbolic in its own way as our own nightly dreams, and likewise encoded in the language of symbols and subtle correspondences. Nested within that cosmic dream are the smaller dreams of both groups and individuals, all seamlessly intertwined like threads in a vast quilt. As a result, a single, isolated coincidence occurring for any one individual actually takes place within the context of this larger infrastructure of meaning that suffuses all these different levels.

So how would such a broad vision specifically alter our understanding of Jung’s model of synchronicity? I think it can be boiled down to a few essential points.

Most obvious of all is the matter of frequency—that is, how often does synchronicity really occur? On the one hand, Jung spoke of synchronicity as an acausal connection between an outer event and an inner psychological state, or between two external events. In either case, he described it as a “relatively rare” phenomenon, a decidedly infrequent eruption of meaning in our lives. Employing the symbolist approach, however, we find there are actually many eruptions of meaning in our lives, occurring in a wide variety of contexts. Taking a hint from the esoteric traditions, we could include such seemingly common developments as the births of children, chance encounters with strangers or animals, life tragedies, changes in the workplace, travel experiences, health problems, nightly dreams, and anomalous events of any sort. All of these—and many more—are meaningful eruptions, with deep acausal connections to broader patterns of significance in our lives, all playing their own role in the phenomenological drama of everyday experience.

But considering how all-pervasive synchronicity becomes according to such a view, how shall we begin to sort out the proverbial signal from the noise in unearthing meaning from ordinary experience? In The Waking Dream, I suggested a simple rule of thumb: to focus attention particularly on those events which are most unusual or out of the ordinary. If you have a subscription to a daily newspaper, say, finding a copy on your doorstep is nothing particularly significant. But suppose you have never subscribed to any newspaper and one day find a copy at your front door. That suddenly takes on significance, with the meaning perhaps being revealed by the symbolism of the headline that day, or perhaps even by the subject of a phone conversation you were having at the moment you found it.

In formulating his theory of synchronicity, Jung focused his attention strictly on coincidences of a simultaneous sort—that is, those which specifically take place in the same moment in time. Jung’s story about the scarab is one example; another would be receiving a phone call from a childhood friend at the same moment an old letter from them falls out of a book you just pulled off the shelf. Such events synchronize in time—hence Jung’s term synchronicity.

Prior to Jung, though, the Austrian biologist Paul Kammerer undertook his own study of coincidences but focused instead on coincidences of a sequential sort, those which happen consecutively. For example, an obscure old song might pop up numerous times over the course of a single day, one after the other, in completely different contexts. Looking at such events, Kammerer termed his own theory seriality, emphasizing the consecutive rather than simultaneous character of coincidences. (For a discussion of Kammerer’s theory, see Arthur Koestler’s Case of the Midwife Toad.)

At its broadest, the symbolist worldview dispenses with any strict emphasis on simultaneity or sequentiality, instead opening up to acausal connections of all types—sequential or simultaneous, obvious or subtle. As the symbolist perspective of astrology illustrates in particular, the synchronistic tapestry of correspondences extends in all directions, through both time and space.

Whereas Jung saw synchronicity strictly as a personal phenomenon, related to the psychodynamics of individuals, the symbolist worldview sees acausal connections taking place on at least three distinct levels: personal, collective, and universal. I mentioned the coincidence between the mutiny on the Bounty and the French Revolution as a synchronicity involving groups rather than merely individuals. Another example would be the curious way similar inventions or theories sometimes arise simultaneously in different parts of the world, seemingly without any connection to one another. One famous instance was the development of the telephone by both Alexander Graham Bell and Elisha Gray, both inventors having filed notices with the Patent Office in Washington, D.C., on the very same day, February 14, 1876.

It’s even possible to talk about synchronicity in contexts where neither individuals or groups are involved. For instance, astrologers might examine how a volcanic eruption on a remote Pacific island coincided with a celestial pattern involving the distant planets Uranus and Pluto. Such a connection would constitute a truly synchronistic development in that it’s a truly acausal connection of events, but one that didn’t involve individuals or even collectives in any direct way. Likewise, there are astrologers who study the relationship of planetary configurations to weather patterns throughout the world, whether humans are directly involved or not. In contrast with Jung’s model, in other words, individual human psychologies needn’t even be present or involved for synchronicities to occur.

Conclusion

To borrow William Irwin Thompson’s classic analogy, we are like flies crawling across the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, unaware of the archetypal drama spread out before us. The infrequent and dramatic coincidence simply pulls back the curtain on one small portion of that tableau, which encompasses not just our personal lives but our society, and indeed the entire universe.

As such, synchronicity is the key to a dramatically different cosmology than is suggested by conventional science. Beyond simply implying an intimate relationship between one’s outer and inner world, or a subtle “entanglement” between distant phenomena, it describes a worldview that is both multileveled in its meanings and interconnected in ways far beyond what the literally minded eye can possibly perceive.

While it’s within our grasp to understand that broader worldview, we can’t attain it through any purely literal mindset or mechanistic methodology, let alone through the study of individual coincidences in themselves. Rather, it will need to unfold in partnership with a broader philosophical inquiry into the symbolic and archetypal dimensions of existence itself. That, and nothing less, will allow us to finally perceive the “whole elephant” of synchronicity.

Sources

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. The Complete Writings. Twelve volumes. New York: William H. Wise, 1929.

Grasse, Ray. “Synchronicity and the Mind of God.” Quest, May-June 2006: 91‒94.

———. The Waking Dream: Unlocking the Symbolic Language of Our Lives. Wheaton: Quest, 1996.

Jung, C.G. Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle. Translated by R.F.C. Hull. 2d ed. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton/Bollingen, 1973.

Koestler, Arthur. The Case of the Midwife Toad. New York: Random House, 1971.

Tarnas. Richard. Cosmos and Psyche. New York: Penguin, 2006.

Ray Grasse is author of nine books, including An Infinity of Gods, The Waking Dream, and When the Stars Align. He worked for ten years on the editorial staffs of Quest magazine and Quest Books. His website is www.raygrasse.com. For a deeper dive into correspondence theory and the dynamics of symbolism, see his book The Waking Dream, as well as chapter 36 of his book StarGates. The article has been excerpted from his latest book So, What Am I Doing Here, Anyway? (London: Wessex Astrologer, 2024).