Printed in the Fall 2020 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Johnson, Zane, "The Tragic Consciousness in Literature and Tradition" Quest 108:4, pg 26-30

By Zane Johnson

Many seekers today set out on their paths to find something that society is not giving them. In the face of ecological destruction, unflinching individualism, and a general sense of separation and desperation, people are looking for something not quite so tragic as what is currently on the table. Religion and its close cousin, literature, are the great resources in the human search for dignity and meaning. Myth, poetry, and drama can be powerful pathfinders out of this seemingly modern malaise, because they tell us that this search for something more is not ours alone but is woven into the fabric of human existence.

Many seekers today set out on their paths to find something that society is not giving them. In the face of ecological destruction, unflinching individualism, and a general sense of separation and desperation, people are looking for something not quite so tragic as what is currently on the table. Religion and its close cousin, literature, are the great resources in the human search for dignity and meaning. Myth, poetry, and drama can be powerful pathfinders out of this seemingly modern malaise, because they tell us that this search for something more is not ours alone but is woven into the fabric of human existence.

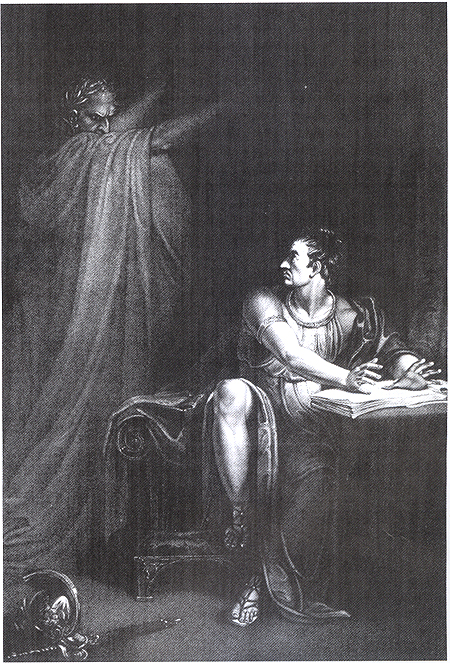

In his article “The Comic Mode,” literary critic Joseph W. Meeker defines the primary value of tragic drama as “avoiding or transcending the necessary in order to accomplish the impossible.” In distinction to comedy, which, like ecology, is a system “designed to accommodate necessity and encourage acceptance of it” (Meeker, 163), tragedy presents a version of reality based on power, struggle, pain, ambition, and commitment to an impossible ideal that leads the tragic hero to his (and it is usually his) ultimate end in death. One thinks of Shakespeare’s Brutus or Macbeth, feeling put upon by the cosmos or history to prove that “men at sometime were masters of their fates” (Julius Caesar, 1.2.139). Tragedies like Hamlet begin with the rupture of communal and familial bonds and proceed to the all-too-familiar end. Nature is cruel, as in King Lear, and serves only as an organic parallel to his court’s possession by dark psychological forces that seek to punish him. It is a staggered path into dissolution, from whence we only see a few hints of renewal at the end.

Comedies, on the other hand, usually follow a dialectical pattern, which sees a cast of characters move from an initial stage of uneasy stability to disorder as unruly passions are sorted out, and finally to renewal and restoration of order. In Shakespeare, this renewal often occurs in a “green world”—one thinks of A Midsummer Night’s Dream and the chaos of human affections that is eventually tamed within an enchanted forest. Such a mode of literature extols the biological and communal over the ideal and individual and tends to highly value the bonds of human relationship and community. In As You Like It, this comfort in community extends, surely enough, to the natural world, where one “finds tongues in trees, books in the running brooks, / Sermons in stones, and good in everything” (2.1.16–17).

Everybody gets what they want in the end, and some primordial inkling that life is in fact good is fulfilled.

What does the foregoing have to do with those inner traditions, those ancient springs of wisdom to which people are turning for an alternative to tragic reality? My suspicion is, sadly, that the language of some these traditions, particularly the Western mystery traditions (with which I am the most familiar), often reproduce a tragic vision of reality, or what I call “tragic consciousness.” Wisdom is not immune from accreting elements from the surrounding culture.

|

|

| The ghost of Caesar taunts Brutus about his imminent defeat. (Engraving by Edward Scriven, from a painting by Richard Westall based on Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, act 4, scene 3, London, 1802. Wikipedia.) |

Part of the dilemma could be the enduring legacy of the nineteenth-century occult revival, which came upon the heels of the Romantic movement. In his article in The Church Times, which details the astonishing involvement of Anglo-Catholic clergy in Theosophy and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, Richard Yoder argues that both at the exoteric and esoteric levels, religious life was engaged in “a defense of the supernatural in the face of modern materialism.” This was, of course, an extension of Romantic values: a defense of the imagination against reason, nature against the despoliations of industrial capitalism, the individual against oblivion. Romantic closet dramas reveled in tragic consciousness, and it comes as no surprise that writers such as P.B. Shelley and Lord Byron constituted a “satanic school” of literature of their own to their contemporary critics. Prometheus Unbound and Cain characteristically reevaluate traditional satanic antiheroes as misunderstood revolutionaries, contained by powers of social and religious tyranny.

Of course, some of these values are fraught with a volatile self-against-the-world dualism. It is now a commonplace to suggest the direct influence of Romantic values—left unchecked and unbalanced—on twentieth-century fascist ideology. Many an occult personality of this same period also had fascist leanings. One need not scour too long the works of Aleister Crowley before coming up against repulsive statements about women, Jews, and the wretched of the earth, coupled with visions of a genetically engineered superrace that manipulates the ignorant masses towards the achievement of their True Wills. In a comment on chapter 3 of his channeled text Liber AL vel Legis, for example, he asks, “Should we not rather breed humanity for quality by killing off any tainted stock, as we do with other cattle?”

Statements in Crowley’s Liber AL, particularly in the third chapter, are also remarkably similar to sentiments expressed in Shakespearean tragedy (Crowley is notorious for literary appropriation in his inspired works). Compare Liber AL’s “Lurk! Withdraw! Upon them!” (Crowley, 314) to Julius Caesar’s “Revenge! About! Seek! Burn! Fire! Kill! Slay!” (3.2.200).

Occult fascism may be the outer extreme of the tragic mode, and we may affirm with Traditionalist esotericists like René Guénon that such occult currents represent a counterinitiation. But even within the Traditionalist framework, tragic consciousness predominates. In Defending Ancient Springs, Kathleen Raine, poet and founder of London’s Temenos Academy, states plainly that “genius is not democratic” (46).

Tragic consciousness affects those of us engaged in plumbing the depths of the traditions we’ve inherited in a more routine way. The hangover from the nineteenth-century occult revival and its historical and philosophical baggage affects how we conceive the spiritual life at a fundamental level.

Our language often seems to present the initiate as special in some way and can foster a sense that we have raised ourselves up from the ranks of the unenlightened masses. I believe this is mostly an error in language, but it can become potent as our unenlightened ego seeks a foothold. (The contemporary British Kabbalist Z’ev ben Shimon Halevi indicates that the initial zealotry and self-aggrandizement that can develop when one begins on a spiritual path can be corrected through a rule of silence: Halevi, 274.)

The esoteric is not for everyone, nor is everyone seeking it. And that’s fine. In her classic Esoteric Christianity, Annie Besant describes secret Christian teaching as just that—something secret, not intended for everyone. She further suggests that it is only for those that can rise above the general intellectual torpor of their contemporaries and be admitted into the temple. One might be forgiven for feeling unnecessarily excluded. Even worse, it could inflame the pride of the curious and encourage a sense of superiority.

Besant describes the qualities that the candidate for the mysteries must develop to be admitted: first discrimination, then disgust, then on to other, less threatening-sounding virtues, such as control of thoughts and endurance. Disgust is the one I want to focus on now. To be fair, she describes it not as disgust with creation or with human beings per se, but rather with “the unreal and the fleeting” (Besant, 174). Yet this can be a major stumbling block to anyone seeking the way and, in my opinion, should eventually be transcended.

When I first began a meditation practice early on in my spiritual inquiry, I was working at a kitchen. I remember discovering at the end of the night shift a maggot that had made a home for itself underneath the soda fountain, feeding on the syrup that fell beneath the grate. And I remember thinking: that’s it. That’s what we are, always too content to suck our sugar cubes in blissful ignorance. I felt disgust.

Of course, I was all too eager to point my finger at those around me and not at myself. But I did experience a sudden, profound aversion to reckless, aimless pleasure-seeking at the expense of the planet and other human beings. Admittedly, it did have an unwelcome effect on my relationships. As Jesus reminds us, “Ye shall know them by their fruits” (Matthew 7:16). This idea had outlived its usefulness to me as an impetus to deeper inquiry into Reality, and I struggled to let go of it.

When describing the higher meanings of atonement and sacrifice in the Christian mysteries, Besant affirms the basic truth that walking the spiritual path is fundamentally not for ourselves, but for the world (a “comic” as much as a cosmic truth). For the real, suffering, flesh-and-blood people and other sentient beings in our lives. This is “the life of love,” which is always other-oriented, and which is summed up beautifully as the Fruit of the Holy Spirit of St. Paul (Besant, 187).

There is an allure to taking too seriously the thought that we have some knowledge that the world does not and which makes us important. It is bewitching in a way, a thought that enchants us when the weird sisters of our imagination talk us into accepting a kind of spiritual viciousness towards others through which our imagined kingship should be gained. And the usual results follow.

Oftentimes the impulse to “conversion,” to begin our own spiritual inquiries, comes at the behest of a voice within us that tells us that things are not as they seem. There is more to this life of grasping after recognition and ephemeral pleasures, this life of sorrow and loss, than we have been led to believe. And this should be a cause for joy! Yet often it only seems to reaffirm the attitudes that we sought to escape in the beginning: that this world and creation are fallen, that pleasure is bad, that there is something wrong with our lives because they never seem to measure up to the impossible tragic ideals that we have somehow absorbed along the way. People and nature become merely instrumental to us as we retreat into our own spiritual ambition.

This is not to say that we should start from scratch and invent other lateral paths of spiritual seeking (though this too has its place). Nor does it mean that we can’t benefit from looking to other paths whose teleology is more horizontal and inclusive. There are a number of means to experience more comic consciousness in our spiritual lives.

The wisdom of the Kabbalah tells us that the Pillar of Severity is just as important to the divine plan for creation as is the Pillar of Mercy. There is a place for the tragic mode in our seeking too, and it can often be a great impetus to us early in our paths. In Buddhism, the Four Noble Truths certainly express tragic consciousness but are mediated by other compassionate teachings like those of the Brahmaviharas.

In my academic work, which helped inspire this reflection, I have lately focused on the intersections between literature, ecology, and religion in the English Renaissance. I have been delighted to encounter Renaissance Hermetic texts anew and read reflections on them from literary writers of the time that seem to affirm the intuitions found in comic literature.

“Sure! there’s a tie of bodies,” as poet Henry Vaughan put it: a pulsing vitality that binds all sentient and nonsentient beings and valorizes life, matter, and embodiment (Di Cesare, 152). The world is infused with the anima mundi, and as the great martyr for wisdom Giordano Bruno put it, “that one and same thing . . . fills everything, illuminates the universe, and directs Nature to produce her various species suitably” (in Borlik, 57). This is surely esotericism in the comic mode.

The esoteric tradition of Renaissance Hermeticism and alchemy appears to express a comic rather than tragic consciousness, intuiting in nature and human life a vital force that sanctifies embodiment and materiality. Emphasis is on unity rather than division. Reaching its peak in the early days of the Reformation, when communal, sacramental rites were discontinued overnight, Renaissance esotericism also helped ameliorate the rift between humans and between humanity and nature.

In a time when forces of disintegration and isolation in the social and natural spheres are rapidly gaining speed, the older tradition can again come to our aid. As pointed out in their manifesto Green Hermeticism: Alchemy and Ecology, Peter Lamborn Wilson and his colleagues claim that there is an opportunity in these sacred sciences for ecological renewal, to help us “explore the riches contained in the magical confluence of our present time and consciousness with the divine gifts now available to all through Nature” (Wilson, Kindle position 134).

The other way that I have been able to integrate the comic mode in my own spiritual life has been to reembrace exoteric religion as a supplement to esoteric study. This will certainly not be a popular position, and indeed it took a lot of time for me to come to it, but I must admit, along with the Traditionalists, that the exoteric is inseparable from the esoteric. They inform and balance one another. Certain esoteric concepts or symbols within the Western traditions are incomprehensible without a thorough familiarity with Judeo-Christian scripture and tradition.

This is also a lesson we can take from the Renaissance esoteric stream of tradition, from whose fonts the conventionally religious—even the Puritanical—freely drew. Think of Anglican priests John Donne or George Herbert. In his poem “Man” Herbert presents a worldview grounded in relationship, analogy, and entanglement, in which

Man is all symmetrie,

Full of proportions, one limbe to another,

And all to all the world besides.

This vision of humanity in the cosmos is a supremely beneficent one, one of belonging, in which “all things unto our flesh are kinde” (Hutchinson, 90).

I think this general optimism about life is common to more conventional forms of religion but is harder to come by in esoteric circles. Anglo-Catholic spirituality has been very important for me lately in living the values of community, companionship, and service that isolated study and practice could not. And yet the meat of the tradition is still to be discovered in private contemplation. It is not either/or—a choice made by all tragic heroes—but both/and. Believe the good news!

In this time in history, when we are becoming increasingly aware of our need for new structures, new ways of expressing communal bonds, and new ways of thinking about inherited tradition, it can be helpful to look back to the vast stretch of human history in which people relied on one another and on their natural environment for spiritual and physical nourishment.

To return to Meeker’s piece quoted at the beginning of this article, he makes the interesting observation that “whole cultures have lived and died without producing tragedy or the philosophical views that tragedy depends on” (Meeker, 157). Perhaps it is time to reevaluate why tragic consciousness has taken such preponderance in Western initiatory streams and whether the time might be ripe to smooth down our edges as seekers and, along with Prospero at The Tempest’s end, commit our all-powerful wands to the sea and walk free from our self-imposed isolation from deeper springs of tradition, history, and community.

Sources

Besant, Annie. Esoteric Christianity. New York: Bodley Head, 1902.

Borlik, Todd Andrew, ed. Literature and Nature in the English Renaissance: An Ecocritical Anthology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Crowley, Aleister. Liber AL vel Legis, 1904. OTO Library (website), accessed June 29, 2020: https://lib.oto-usa.org/libri/liber0220.html.

Crowley, Aleister. The New and Old Commentaries to Liber AL vel Legis, The Book of the Law, 1920. Hermetic Library (website), accessed June 30, 2020: https://hermetic.com/legis/new-comment/index.

Di Cesare, Mario A., ed. George Herbert and the Seventeenth Century Religious Poets: Authoritative Texts and Criticism. New York: W.W. Norton, 1978.

Halevi, Z’ev ben Shimon. Adam and the Kabbalistic Tree. York Beach, Maine: Samuel Weiser, 1974.

Hutchinson, F.E., ed. The Works of George Herbert. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1959.

Meeker, Joseph A. “The Comic Mode.” In The Ecocriticism Reader, edited by Cheryll Glotfelty and Harold Fromm. Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press, 1996: 155–69.

Raine, Kathleen. Defending Ancient Springs. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Wilson, Peter Lamborn, et al. Green Hermeticism: Alchemy and Ecology. Great Barrington, Mass.: Lindisfarne, 2007.

Wells, Stanley et al., ed. The Complete Oxford Shakespeare: Comedies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987. Citations from Shakespeare refer to this volume and the one below.

———. The Complete Oxford Shakespeare: Tragedies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Yoder, Richard. “On the Wings of the Dawn: The Lure of the Occult.” Church Times, Dec. 14, 2018: https://www.churchtimes.co.uk/articles/2018/14-december/features/features/on-the-wings-of-the-dawn-the-lure-of-the-occult.

Zane Johnson is a poet, translator, and student of the mysteries. Recent work has appeared in Asymptote, No Man’s Land, Anatolios Magazine, The American Journal of Poetry, and elsewhere. He currently studies literature, translation, and the environmental humanities at the University of Munich.