Printed in the Fall 2022 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Smoley, Richard, "The Other Worlds of Emanuel Swedenborg" Quest 110:4, pg 29-34

by Richard Smoley

The concept of other worlds—that is, the idea that there are other planets in the solar system and, possibly, the universe with inhabitants recognizably like our own—has a longer history in the West than one may first imagine. The idea can be traced back to the Greek philosophers Leucippus (fifth century BC), Democritus (c.460‒c.370 BC), and Epicurus (341‒270 BC), who were the first to formulate an atomistic theory of the universe. Atoms in this sense consist of small, invisible, and indivisible particles of which all things were composed. All things were generated by their combinations and recombinations, including the sun, the stars, and the planets.

Since the number of atoms was supposed to be infinite, it would follow that the number of worlds would be infinite as well. One ancient source characterized Democritus’s views as follows:

He spoke as if the things that are were in constant motion in the void; and there are innumerable worlds, which differ in size. In some worlds there is no sun and moon, in others they are larger than in our world, and in others more numerous. The intervals between the worlds are unequal; in some parts there are more worlds, in others fewer; some are increasing, some at their height, some decreasing; in some parts they are arising, in others falling. There are some worlds devoid of living creatures or plants or any moisture. (Hippolytus, Refutation of All Heresies, 1.13.2; in Kirk, Raven, and Schofield, 417‒18)

This account has proved remarkably robust: the views of a modern physicist could be described in the same way with only slight changes in wording. Democritus’ theory is all the more impressive because there was no empirical evidence for the existence of these other worlds until much later: the moons of Jupiter would not be discovered until the seventeenth century, and exoplanets—planets in other solar systems—would not be discovered until the late twentieth century.

Democritus’ views about other worlds were derived from the implications of his basic theory. The same could be said of all theories of other worlds until well into the early modern era. Aristotle, for example, held quite a different view of the universe, based largely on his own system of physics. The universe was composed of four elements: earth, air, fire, and water, each of which had its own natural motion and place—that is, its own natural position toward which it moved unless otherwise impeded: earth tended to move toward the center of the world; fire moved away from it, with the other two elements occupying places in between. For Aristotle, then, there could only be one world, because if there were more worlds, earth would have two directions in which to move—a possibility that he did not admit (Dick, 14‒18).

The Aristotelian worldview consisted of a central and static earth, around which the five known planets and the two luminaries revolved in concentric circles in this order: the moon, Mercury, Venus, the sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, beyond which was the sphere of fixed stars. This picture of the universe, with elaborations by the astronomer Claudius Ptolemy (c. AD 90‒c.168), would prevail in the West until the Copernican revolution of the sixteenth century.

Nevertheless, the debate about other worlds and extraterrestrial life surfaced from time to time in antiquity. One example appears in a dialogue by Plutarch (AD c.46‒c.120) entitled On the Face on the Orb of the Moon. Plutarch discusses whether the moon is habitable and indeed inhabited. Although the treatise is more literary than scientific in intent and reaches no definitive conclusion, it does not attempt to prove that the moon cannot be inhabited, leaving the ultimate answer open.

Another, lighter approach was taken in a romance by the Greek satirist Lucian of Samosata (c.AD 120‒after 185) entitled The True History, which tells of a journey to the moon by Lucian and his cohorts. Hailed by some as the first work of science fiction, it is clearly satirical and does not indicate any genuine belief in life on other planets on the author’s part. The book has exercised some influence over the centuries—but almost entirely on satirists and not on scientists (Dick, 20‒22).

In the high medieval period, Aristotle’s views, reintroduced to the West by the Arabs and harmonized with Christianity by figures such as Thomas Aquinas, came to dominate the world of Catholic thought to the point of approaching religious dogma. Hence at this time the idea of other worlds was in eclipse, and was only rescued in 1277, when Étienne Tempier, bishop of Paris (c.1210‒79) issued a condemnation of 219 beliefs that he called heretical; among these was the notion that “the First Cause [i.e., God] cannot make many worlds” (Dick, 28). Again the belief in other worlds was not in itself of primary concern: Tempier was not so much concerned to protect it as to oppose any notion that might suggest limits to divine power.

Other late medieval thinkers considered the possibility of inhabited worlds, including the German cardinal Nicholas of Cusa (1401‒64) and the Franciscan theologian William Vorilong (d. 1464), who contended that “not one world alone, but that infinite worlds, more perfect than this one, lie hid in the mind of God,” and that such a world could have intelligent inhabitants that “would exist from the virtue of God, transported into that world” (in Crowe, 27).

After Copernicus

The debate about extraterrestrial life began to take its present form with the Copernican revolution, which posited the sun rather than the earth as the center of the universe. By displacing the earth in this way and positioning it as merely one of several planets, the Copernican theory opened new ground for other-worlds discussions, although Copernicus himself did not engage in it (Dick, 63).

It took the original and highly controversial scholar Giordano Bruno (1548‒1600) to bring the issue forward again. In a 1584 work entitled De l’infinito universo et mondi (“On the Infinite Universe and Worlds”), Bruno argued that the stars were suns, these planets had “earths” orbiting them, and that both these suns and these “earths” contained inhabitants (in Crowe, 49). Bruno’s views, on this and many other subjects, attracted the disfavor of the Catholic Church, and the Inquisition burned him at the stake in Rome in 1600. While he was willing to recant on some of his theological criticisms of church doctrine, he held to his belief in infinite worlds till the end.

In the early seventeenth century, the debate resumed with renewed vigor because of a revolutionary discovery by the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei (1564‒1642). Using the newly invented telescope, he observed that Jupiter had four moons orbiting it. This advanced the theory of heliocentrism (which at that time had not yet been fully accepted): if Jupiter could have moons, the earth could certainly have one moon while revolving around the sun.

Johannes Kepler (1571‒1630) took this argument one step further: “Our moon exists for us on the earth, not for the other globes. Those four little moons exist for Jupiter, not for us. Each planet in turn, together with its occupants, is served by its own satellites. From this line of reasoning we deduce with the highest degree of probability that Jupiter is inhabited” (in Crowe, 60‒61).

This argument reveals a great deal about the nature of scientific debate in the era. Kepler was arguing that the cosmos was created for a purpose, namely to serve man, or at any rate a being like him. The sun, moon, and planets could be said to serve man’s purposes (in providing light and heat and so forth), but what possible use to humanity could the moons of Jupiter serve? As a result, Jupiter must be inhabited, because it must have rational beings for whom the moons were created.

As this discussion shows, teleology was extremely important in the causal thinking of the early modern scientists: in order to consider why something should exist, we need to look at, not only what brought it about (its effective cause, to use the Aristotelian term) but its final cause. Without a final cause, a purpose, a thing had no place in the universe—a conclusion which cast aspersions on the wisdom of God in his arrangement of the cosmos, and which was therefore inadmissible. This argument would soon look untenable; in certain ways, the history of early modern science is the history of the expulsion of the final cause from scientific reasoning—to the point where today practically any teleological concept is taboo in mainstream scientific discussion.

Galileo, no doubt mindful of Bruno’s fate, was chary of advancing the idea of other worlds (Dick, 90), although his caution did not save him from condemnation by the Inquisition and lifelong house arrest for advocating heliocentrism.

The French philosopher René Descartes (1596‒1650) showed caution as well. His Principia philosophiae (“Principles of Philosophy”) set forth the first new physical system since Aristotle—one that propounded the existence of innumerable vortices in the universe, at the center of each of which was a fixed star. While this naturally suggested the possibility of other planets with inhabitants on them, Descartes remained carefully agnostic on this point (Dick, 111‒12).

This was not the case with Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle (1657‒1757), one of the leading figures of the French Enlightenment. In a 1686 work entitled Entretiens sur la pluralité des mondes (“Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds”) Fontenelle explicitly tied Descartes’s concept of vortices to the possibility of other worlds. The Entretiens was a light, witty book, which meant two things: (1) Fontenelle could hide behind the veil of jest in propounding his ideas, which he nonetheless took at least somewhat seriously; and (2) the Entretiens became enormously popular, going through many editions in the late seventeenth century (Dick, 123‒26), widely disseminating the idea of other worlds among the literate public.

The Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens (1629‒95) took a more serious tack but drew similar conclusions in his Cosmotheoros (“Observer of the Universe”), posthumously published in 1698. Like Kepler, Huygens uses teleological arguments to advance the idea of other inhabited planets: they must have life because life better manifests divine Providence than lifeless planets, and without it “we should sink [the planets] below the Earth in Beauty and Dignity; a thing that no Reason will permit” (in Dick, 130).

The second half of the Cosmotheoros discusses the nature of life on these planets—obviously a wholly speculative discussion, although it is based on observed phenomena as the relative distance of each planet from the sun (Huygens believed that, although Mercury would, from its proximity to the sun, receive nine times more heat than the earth, he also contended that its inhabitants would be adapted to these conditions.)

Although Isaac Newton (1642‒1727) did not explore this idea in any great detail, it was in his time and place—late seventeenth-century England—that the concept of other worlds became part of mainstream scientific opinion, being propounded by figures such as Richard Bentley (1662‒1742), William Whiston (1667‒1752), and William Derham (1657‒1735). One reason for this occurrence was that England permitted much greater liberty of religion than existed in the Catholic world, or even in many other Protestant countries. Another was that the great religious wars of the previous century had weakened faith in Scripture as testimony to God’s will and providence, and correspondingly strengthened the desire to see God’s handiwork in the natural universe. Because, as the argument went, the majesty and wisdom of God would be better demonstrated in a plurality of worlds rather than in a single one, many scientists began to incline toward this wider perspective.

Swedenborg’s Scientific Period

|

|

|

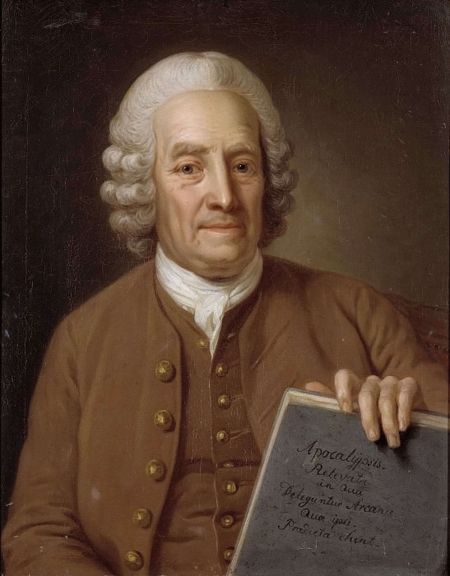

The Portrait of Emanuel Swedenborg, by Per Krafft the Elder, is from 1766. It shows Swedenborg at age seventy-five, holding the soon to be published manuscritpt of his Apocalypsis Revelata ("Apocalypse Revealed"). Image by courtesy of the Swedenborg Foundation. |

In an early phase of his thought, the great Swedish visionary Emanuel Swedenborg (1688‒1772) reflects some of these themes and concerns. Swedenborg’s early works were scientific. One of them, ThePrincipia (1734), includes a short chapter entitled “The Diversities of Worlds” (Swedenborg, Principia, 2:240‒48) His arguments here, recapitulating many themes of the debate from the earliest times, argue in favor of the idea of other worlds.

Swedenborg begins with what is sometimes called “the argument from plenitude,” contending that nature “is most profusely fertile and ever essaying at further ends, inasmuch as she is never at rest, but always desirous to advance and extend the bounds of her dominion.” Like many of his predecessors, he argues that divine glory and omnipotence suggest that this is not only possible but likely: “Nor is there anything to prevent us from conjecturing that at the will of the deity may arise fresh systems at every moment; for there is nothing to shew that it is physically impossible” (Principia, 2:240‒41). At the end of the chapter he will say that God “can give birth to nature not only after the manner in which it is presented to our view in this world, but in ways infinitely diversified” (Principia, 2:247‒48).

Just how diversified? Just how much could these worlds differ from one another? The problem exercised Newton, who wrote in a letter to Richard Bentley:

And since Space is divisible in infinitum, and Matter is not necessarily in all places, it may also be allow’d that God is able to create Particles of Matter of several Sizes and Figures, and in several Proportions of Space, and perhaps of different Densities and Forces, and thereby to vary the Laws of Nature, and make Worlds of several sorts in several Parts of the Universe. At least I see nothing of contradiction in all this. (In Dick, 146‒47)

Swedenborg’s answer is similar but not identical. While he does admit great variances in the properties of other worlds, he also holds that some principles will apply universally: “In every mundane system, the principles of geometry continue to be similar; as also nature and mechanism, as to first principles and force; and that the diversity consists only in the diversity of the series, in respect to degrees, ratios, and figures” (Principia, 2:245‒46).

Swedenborg is arguing that certain basic principles will remain constant in all systems, such as the laws of geometry (non-Euclidean geometries would not be developed until the nineteenth century), as well as “nature and mechanism, inasmuch as its motive forces cannot be separated from geometry.” These principles remain, as it were, axiomatic, but the series and modes in which they operate can vary; the elements may display different properties; in some worlds, even, the animals might be “deprived of the use of their senses” (Principia, 2:246).

From these two passages it would seem that Newton is more ready to admit possible variations in basic principles than Swedenborg is. Whichever view one takes, however, the same question applies: how different can these worlds be from our own before they are unknowable to us? This question is not addressed. While Swedenborg says that the phenomena of these other worlds might differ so much that “the learned of those worlds . . . might excite only a smile from the learned of ours” (Principia, 2:247), he does not ask whether they might differ so much that the learned of these worlds would be totally and irreversibly isolated from us.

Swedenborg goes on to say that these systems, which could arise at different times, would nonetheless display some resemblance to the Earth’s own life cycle: “We may also conjecture, that each earth in its infancy would be similar to ours in its infancy.” Swedenborg associates this “infancy” with the Golden Age of the earth, suggesting that each of these worlds would “exhibit the bloom of youth in its infant state.”

Swedenborg admits that the concept of other worlds is speculative: “from a mere possibility . . . we cannot reason to actuality” (Principia, 2:241). He goes on to emphasize the limits of our knowledge, not only of these putative other worlds, but even of our own: “In the mineral, vegetable, and animal kingdom, what we now know is nothing to what we have yet to learn; for of that of which our senses are unconscious, the soul also is ignorant” (Principia, 2:247). Like everyone else before him in this debate, Swedenborg in his scientific phase comes across the immovable barrier created by the lack of empirical evidence.

Visions of Planetary Beings

It would prove otherwise in Swedenborg’s theological period, which started around 1745, when he began to experience visions of unseen realms, including heaven, hell, and the spirit world. At this point, Swedenborg does attempt to provide empirical evidence for the existence of other worlds and other beings—the evidence being his own experience. He begins his short work Other Planets by describing his experiences with spirits from the planets known in his time: Mercury, Jupiter, Mars, Saturn, Venus, and the moon (in that order). He then proceeds to beings from planets outside the solar system, of which he enumerates five. He does not seem to know of any further planets in our solar system, in keeping with the knowledge of his day: Uranus would not be discovered until 1781, nine years after his death.

These experiences differ radically from later encounters with extraterrestrial creatures, real or imagined, in one chief respect: Swedenborg is not dealing with these beings as they lived in physical form, but rather with their spirits. Nonetheless, he makes it clear that these spirits originally had physical bodies on their respective planets, just as inhabitants of earth have.

Swedenborg does not appear to be interested in drawing general conclusions about beings from other worlds, or what this might imply for scientific knowledge; rather he limits himself to concrete descriptions of these inhabitants, their patterns of mind, and their way of life. His work has one chief purpose: to show that “not enough people come into heaven from our world to make up [the] universal human. We are relatively few, and there must be people from many other worlds. So the Lord has provided that the moment any nuance of quality of substance of this responsive relationship is missing anywhere, people from another world are immediately summoned who fill the need so that the proper proportion is established and heaven therefore stands firm” (Swedenborg, Other Planets, 9).

In Swedenborg’s thought, the universal human (maximus homo in Latin) is a gigantic heavenly being of which each individual is a cell. The spirits of the planet Mercury, for example, correspond to “memory, specifically memory of things beyond things of earth and of mere matter” (Other Planets, 9).

It is tempting to look for some connection between Swedenborg’s descriptions of these spirits and the characteristics of the planets as they were portrayed in the Western esoteric tradition and in astrology. In general, the correspondences are present but faint. See, for example, a typical description of the characteristics of Mercury by Henry Cornelius Agrippa (1486‒1535) in his classic work De occulta philosophia (“On the Occult Philosophy”):

Mercury is called the son of Jupiter, the crier of the gods, the interpreter of gods, Stilbon, the serpent-bearer, the rod-bearer, winged on his feet, eloquent, bringer of gain, wise, rational, robust, stout, powerful in good and evil, the notary of the Sun, the messenger of Jupiter, the messenger betwixt the supernal and infernal gods, male with males, female with females, most fruitful in both sexes, and Lucan calls him the arbitrator of the gods. He is also called Hermes, i.e., interpreter, bringing to light all obscurity, and opening those things which are most secret. (Agrippa, 2:49, 427)

Some traits of this occult Mercury are echoed in Swedenborg’s Mercurial spirits: in their collection and retention of impressions from many worlds (see Other Planets, 15) they can be said to have a kind of role as messengers; moreover, like the itinerant messenger of the gods, “they do not settle down in one place, . . . but roam through the universe” (Other Planets, 24). On the other hand, unlike the communicative Mercury of the occult philosophy, “bringing to light all obscurity,” Swedenborg’s Mercurians have a “custom of not giving direct answers to questions,” and “have a distaste for verbal speech” (Other Planets, 17).

Although these resemblances are faint, we can still ask whether Swedenborg was somehow influenced by this occult philosophy, which was then much more widely known and respected than it is in our day. The answer is difficult to give, and will certainly vary with one’s approach to Swedenborg’s writings as a whole. Those who take his writings as the fruit of divine inspiration will insist that he was reporting his own spiritual experiences and that he was not at all influenced by these earlier traditions. A more skeptical reader might be willing to see some traces of this influence on Swedenborg.

It is also tempting to correlate Swedenborg’s description of these planetary inhabitants with Dante’s astrological schema in The Divine Comedy, which is particularly evident in the Paradiso. In his ascent through the concentric spheres of the planets (Dante’s schema is based on Aristotle’s), Dante encounters souls at every level that embody the virtues of that planet. The moon, being the most rapidly changing of the heavenly bodies, is the realm of the inconstant. Mercury is the realm of seekers after glory. Venus, the planet of love, is the domain of lovers; the sun is the realm of the wise; Mars, of the warriors of the faith; Jupiter, of just rulers; Saturn, of contemplatives. While not absolutely identical to the occult schema in Agrippa’s Renaissance text, it is certainly close enough.

All of this is very far from Swedenborg. He does not take the planets in their traditional order; his descriptions of the beings of each planet bears only a faint resemblance to their astrological correspondents; he does not view his own journey in the form of an ascent; nor are the planets spheres of heaven. His extraterrestrials are human, or humanoid, with faults of their own. Mercurians, “because of their wealth of experience,” are more inclined to pride (Other Planets, 16). On Jupiter (traditionally the most benign and beneficent of all the planets) we find practitioners of a sinister priestcraft, who “call themselves saints and demand that their servants . . . call them ‘lords,’” and prohibit these servants from “worshipping the Lord of the universe, saying that they are mediators of that Lord and that their requests will be forwarded to the Lord of the universe” (Other Planets, 70). On Venus, those from the side that faces Earth “are savage and almost feral,” as well as “stupid, with no interest in heaven or eternal life” (Other Planets, 108).

On the whole, however, the inhabitants of Swedenborg’s other worlds seem to be better and kinder than those on Earth. Those who inhabit the side of Venus that faces away from Earth are “gentle and humane” (Other Planets, 108), while Mercurians “are completely unconcerned about earthly and physical matters” (Other Planets, 12). Spirits from Jupiter “are much wiser than spirits from our planet” (Other Planets, 61). Those from Mars “are some of the best from all the worlds in our solar system” (Other Planets, 85). Those from Saturn are “trustworthy and modest” and “profoundly humble in their worship” (Other Planets, 97‒98). Swedenborg does not mention the moral characteristics of the spirits of the moon, no doubt because his description of them is so short (Other Planets, 111‒12).

One last characteristic of these extraterrestrial spirits is worth noting. They do not seem in the slightest bit technologically advanced. Of the spirits from Mars, we learn that “the standard diet on their earth was fruit from trees . . . along with vegetables. They wore clothes that they made from the fibers of the bark of particular trees” (Other Planets, 93). Indeed the inhabitants of Jupiter seem somewhat apelike: “they do not walk upright like the inhabitants of our planet . . . but help themselves along with the palms of their hands” (Other Planets, 55).

Taken as a whole, the lives of these beings seem to resemble that of the primitive humanity of the classical Golden Age. Swedenborg himself contends that “the earliest peoples on our planet lived like that” (Other Planets, 49).

The modern notion of technologically advanced extraterrestrials is completely absent from Swedenborg. Contemporary speculations about extraterrestrials, focusing on visitors to our planet from other planets, presuppose technological sophistication: they could not reach us if they were not far more advanced than us. For Swedenborg, this requirement is unnecessary: no spaceships are required to encounter extraterrestrial beings in the world of spirits.

Swedenborg’s vision of other worlds reveals two main themes. The first, and most important, is the vastness of the universe and the complete inadequacy of the earth alone to fully furnish the population of heaven. The second is an emphasis on certain core values—notably the need to acknowledge the primacy of spiritual as opposed to earthly reality and the need for moral sincerity, and the relative backwardness of the human race in this regard.

Swedenborg’s insistence that his encounters have taken place in the spiritual plane and not on earth have meant that his visions have had very little influence on the subsequent debate regarding extraterrestrials. Moreover, there is no evidence at present for life forms in this solar system that even remotely resemble humans.

One’s response to these facts will vary with one’s attitude toward Swedenborg’s thought as a whole. However literally or metaphorically one wishes to take his encounters with the spirits of planets from this solar system and others, they remain an integral part of his powerful and all-encompassing spiritual vision.

Sources

Agrippa, Henry Cornelius. Three Books of Occult Philosophy. Translated by James Freake and edited by Donald Tyson. St. Paul, Minn.: Llewellyn, 1993 [1533]

Crowe, Michael J. The Extraterrestrial Life Debate, Antiquity to 1915: A Source Book. Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 2008.

Dick, Steven J. Plurality of Worlds: The Origins of the Extraterrestrial Life Debate from Democritus to Kant. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

Kirk, G.S., J.E. Raven, and M. Schofield, eds. and trans. The Presocratic Philosophers: A Critical History with a Selection of Texts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

Swedenborg, Emanuel. The Earthlike Bodies Called Planets in Our Solar System and in Deep Space, Their Inhabitants, and the Spirits and Angels There, Drawn from Things Heard and Seen. Translated by George F. Dole. In Swedenborg, The Shorter Works of 1758: New Jerusalem, Last Judgment, White Horse, Other Planets. Translated by George F. Dole and Jonathan S. Rose. West Chester, Pa: Swedenborg Foundation, 2018.

———. The Principia; or, The First Principles of Natural Things. Translated by Augustus Clissold. Two volumes. Bryn Athyn, Pa.: Swedenborg Scientific Association, 1988 [1734].

Swedenborg’s works are conventionally numbered by sections; references are to these sections rather than to page numbers.

With permission from the Swedenborg Foundation, the above article was adapted from Richard Smoley’s introduction to Emanuel Swedenborg’s The Shorter Works of 1758, New Century Edition, trans. George F. Dole and Jonathan S. Rose (West Chester, Pa.: Swedenborg Foundation, 2018), 84–97.