Printed in the Summer 2020 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Kokochak, Jo, "Ritual in Co-Freemasonry" Quest 108:3, pg 20-24

By Mary Jo Kokochak

My involvement with the Co-Masonic order began in a strange and unique way, as many spiritual quests do. One afternoon, while I was browsing in a bookshop, a copy of The Egyptian Book of the Dead suddenly toppled off a shelf into my hands. A short time later my search led me to the local branch of the Theosophical Society in my hometown of Detroit.

My involvement with the Co-Masonic order began in a strange and unique way, as many spiritual quests do. One afternoon, while I was browsing in a bookshop, a copy of The Egyptian Book of the Dead suddenly toppled off a shelf into my hands. A short time later my search led me to the local branch of the Theosophical Society in my hometown of Detroit.

I’ve long forgotten the subject of the evening’s lecture, but what has stayed with me for the past forty-five years is the unusual experience that happened just afterward. Without any forethought, I found myself walking across the lecture room to one of the members and asking her, “What is Freemasonry?” I knew very little about the Masons and hadn’t consciously thought much about them, so the words sounded strange to my ears.

The woman seemed as startled as I was but said, “I’m an Eighteenth-degree Co-Mason; I’ll tell you something about it.” We set a date for a chat, and I went home.

Later that night, as I was falling asleep, her smiling face came into my awareness, and I journeyed back through the centuries to our life together as mother and daughter. She remained as a dear friend and mentor for many years after I joined both the Co-Masonic Order and the Theosophical Society.

Freemasonry has its modern roots in the craftsmen’s guilds of the Middle Ages: groups of men who traveled throughout Europe building the great cathedrals such as Chartres, Notre Dame, and Amiens. These operative masons became the foundation for “speculative” Masonry, which developed in the eighteenth century as a system of rituals and symbols using builders’ tools to teach moral and philosophical ideas and ideals.

Freemasonry, which opposed the dogmatism and authority of the church, was designed to encourage tolerance and freedom of thought. Its purpose was to create a fraternity by gathering together men of different nationalities, races, religions, and social classes, abolishing all causes of division, and promoting unity.

Present-day Freemasonry in the U.S. is known by most people as a men’s fraternal and charitable organization, and although it teaches morality and ethics, it has lost some of its original purpose, and its lodges bar women; some also exclude men of color from joining.

Co-Freemasonry was founded to correct these omissions. In 1882 an exclusively masculine lodge in France, appropriately named “The Freethinkers,” initiated Maria Deraismes, a lecturer and worker for equal rights for women. These men believed that preventing women from joining was an outmoded custom and that the time had come to bring them into the fraternity. These Masons declared equal rights for both sexes, no limits on the search for truth, and, to ensure this search, maximum tolerance among members. These enlightened French Masons saw that in order for society to progress, women must be provided with the educational advantages of Freemasonry, equality with men in all avenues of life, and the opportunity to take a responsible place in the community.

In 1893 Dr. Georges Martin, a French senator, joined Maria Deraismes and other male Masons in founding Loge Le Droit Humain, Maçonnerie Mixte, known in English as Lodge Le Droit Humain (Human Rights), Co-Freemasonry, the first lodge to admit women equally with men. “Co” referred to men and women working together not merely side by side, but jointly and mutually assisting one another. The founders felt that men and women could come together in an international fraternity to bring human rights to all people, and their lodges were open to men and women of all nationalities, races, and religions. They were against racism, the degradation of women, and religious intolerance, and in fact believed that religions divide humanity rather than unite it. The articles of the first constitution of the Co-Masonic order were and still are essentially those of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of the United Nations.

The movement was destined to expand its purpose through the efforts of Annie Besant, the second international president of the Theosophical Society. Throughout her life, Besant was concerned with the plight of the downtrodden and oppressed and worked for equal rights for women. Learning of this new form of Freemasonry, she saw it not only as a tool for intellectual and moral advancement, but realized its enormous potential for the spiritual development of both men and women. In 1902 she went to France and joined Le Droit Humain, then spread the order throughout the English-speaking world. Her spiritual vision brought new life to the Craft (as Masonry is sometimes known) and joined together the two streams of spiritual self-transformation and service to humanity.

The Supreme Council of Le Droit Humain signed the Besant Accord, which guaranteed its lodges the freedom to practice this new form of Co-Freemasonry. While there is no other formal link between the Theosophical Society and Le Droit Humain, it’s easy to see what the two organizations have in common. Both share a vision of a unified humanity while respecting individual differences and freedom of belief in the search for truth and promoting self-transformation. Many Theosophists have been members, among them international presidents Radha Burnier, N. Sri Ram, C. Jinarajadasa, and George Arundale, and American presidents Joy Mills, John Algeo, and Betty Bland. In 1926 Besant, Krishnamurti, and other Theosophists held a Co-Masonic ceremony laying the foundation stone for the headquarters of the Theosophical Society in America in Wheaton.

Besant and other Theosophists believed that the roots of Freemasonry can be traced back to the ancient Mysteries, particularly of Egypt and Greece. Fellow Co-Mason and Theosophist C.W. Leadbeater wrote two books which shed light on this link, The Hidden Life in Freemasonry and Ancient Mystic Rites. Besant and Leadbeater felt that the ancient rites and rituals have emerged in the present day as Freemasonry. While we can’t say for certain that Freemasonry is an actual revival of the Mysteries, they definitely have certain elements in common.

|

|

|

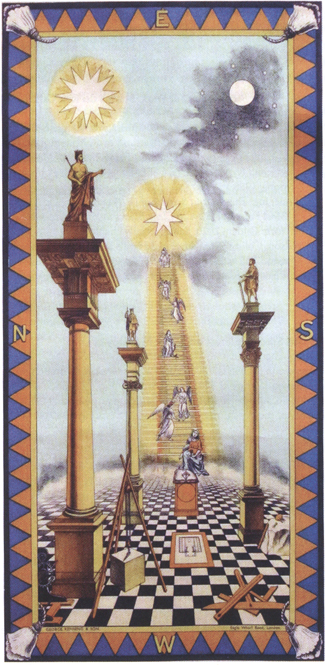

| Fig.1: First Degree: the Apprentice grade |

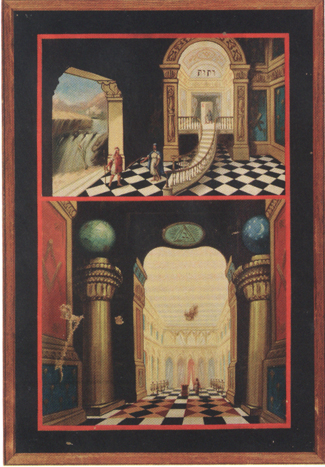

Fig. 2: A tracing board for the Second Degree |

|

|

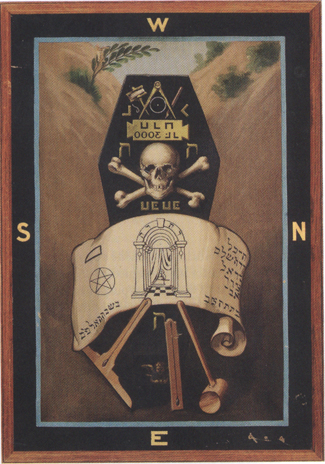

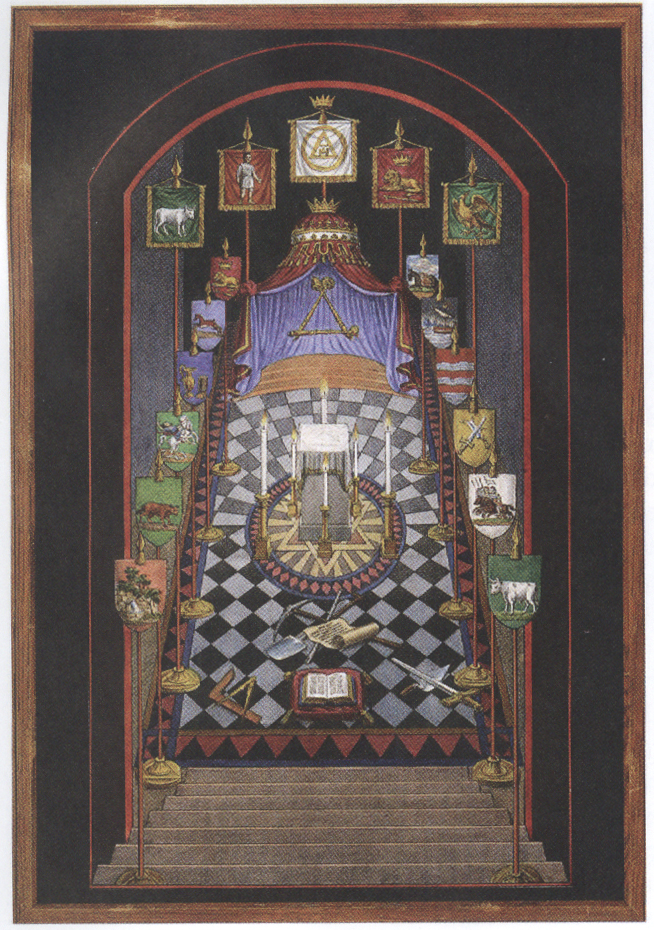

Tracing boards have long been a basic element of Masonic instruction. Their symbols are intricate and multidimensional, with many meanings. Fig.1: Is for the First Degree: the Apprentice grade. Symbols include the checkered pavement, which refers to the material world, with its alternation of positive and negative. The Blazing Star, also known as the Glory, symbolizes the universe as seen from the point of view of the divine. The sun and moon are ancient symbols of complementarity. Jacob’s Ladder in the center represents an ascent through the level of the spirit. Fig.2: A tracing board for the Second Degree, that of the Fellow Craft. Here the staircase is curved to indicate that as the initiate ascends, he must turn his attention from the material world toward the higher levels. Fig 3: A tracing board for the Third Degree: Master Mason. The coffin and skull motif refers to the death of the “old man as a prelude to initiation. Fig 4: A tracing board indicating the layout of the lodge. See W. Kirk Macnulty. Free masonry: A Journey through Ritual and Symbol (London: Thames & Hudson, 1991). |

||

|

|

|

| Fig 3. A tracing board for the Third Degree: Master Mason | Fig. 4: A tracing board indicating the layout of the lodge | |

Co-Freemasonry is essentially a system of rituals and symbols with the purpose of developing morally, intellectually, and spiritually. The system is designed so that it can be interpreted at ever deeper levels depending on the understanding of the Mason. The ideal of service is primary: Masons don’t work for their own personal satisfaction but to develop themselves so they are more capable of helping others.

Members advance through a system of degrees. Each of the three primary degrees depicts what can be called steps on the path of spiritual development and presents an outline of the essential work required in each step. The Mason learns about the great plan of evolution and the opportunity that Co-Masonry presents for taking one’s own development in hand to quicken spiritual progress.

Co-Masonry isn’t a secret society, but it does have certain secrets, so its rituals can’t be described, but generally speaking, the rituals make use of myths and traditions of Egypt, Greece, Israel, the Knights Templar, and the Rosicrucians. A myth is not factual reality but a story designed to impart deeper levels of meaning. The myths of Co-Freemasonry are made alive through the participation of members in dramatic enactments with the purpose of causing meaningful inner change.

One important myth revolves around the construction of King Solomon’s Temple, each Mason representing a stone necessary for the completion of the building. Every stone must fit squarely into the structure so the building will be strong and stable. The Temple represents humanity. The ritual continually reminds us that no one stone is more important than another and that we work on ourselves in order to help humanity as a whole evolve.

This emphasis on unity is built into the ritual of each degree. In this way it discourages the temptation to consider ourselves as more advanced than others as we progress through the degrees.

The lodge is the basis of all Masonic work, and every member belongs to a lodge. In some ways it is similar to the Buddhist sangha, where members are motivated by the same ideals and come together to support one another. Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh defines sangha as “beloved community,” and my lodge has been this for me. When the members are in harmony and working in the spirit of brotherhood and sisterhood, the lodge becomes a spiritual family. Meeting regularly over time, members build strong bonds with one another, and a collective consciousness develops that supports and strengthens the ritual. The power of the group becomes greater than the sum of the individuals participating, so that a deep commitment to the ideals of Masonry and a strong sense of intention adds strength to the work.

Nevertheless, conflicts and difficulties can arise in the lodge, just as they do in the most loving family. Disagreements and pettiness disturb the harmony of the ritual, so tact, patience, tolerance and acceptance are all necessary. But one benefit of working closely together is that as character defects rise to the surface, there is the opportunity to work on them in a supportive atmosphere. This “smoothing of the rough stone” is one of the purposes of the Masonic lodge.

The use of myth, ritual, and symbols differentiates Freemasonry from other organizations having the same purpose of spiritual self-transformation. Lectures, for example, use facts and ideas and speak to the intellect, while a symbol points beyond itself, leading to a more mysterious realm. Symbols unlock the higher quality of intuition and open doors to the unconscious, making that reality conscious. Like a Zen koan, a symbol can give the experience of direct insight, but this doesn’t come automatically, and the ground must be prepared through study and contemplation. Insights come in a flash of “Eureka! So that’s what it means! It’s so obvious! Why haven’t I seen this before?” Since symbols have many levels of meaning, they reveal deeper insights as we grow in understanding. But the mind tends to want a final answer, so it often fixes upon an insight, preventing newer interpretations. The Mason learns to be patient and hold each insight lightly while working toward the next.

Like the ancient Mysteries, Co-Masonic ritual is experiential. How the ritual works retains an air of the unknown. It asks that we use our senses of sight, hearing, smell, and touch and involve our body, mind, and emotions. It asks us to be fully present in the moment, centered, watching and listening to what the ritual is trying to reveal. Although the rituals are unchanging and we repeat the same words and actions at each meeting, no two meetings are ever exactly the same. This is because we ourselves change from day to day and influence the tone and power of each meeting.

Ritual is meant to act on our deeper nature, and perfect ritual requires that we forget ourselves. It’s important that we know what we’re doing and why, but most important is that the Mason becomes the position they are holding and unifies their consciousness with it. This means that we set aside our personality and let it recede to the background. While this isn’t easy, it can be learned. Healing techniques such as Therapeutic Touch and Reiki also involve this kind of impersonality, so that the healer channels universal energy rather than their own.

A sister said that at a recent ceremony, as she was speaking the words to the candidate, the room suddenly came alive with intense light; the words became more than mere words and took on a reality of their own. The ritual was the same as it had always been, and the words were the same as had been spoken often before, but they were now alive with extraordinary spiritual meaning and depth. What brought this about? Was it the preparation of the speaker, the ardor of the candidate, the devotion and concentration of the other members present? Was it all of these and perhaps something more?

Does participation in ritual actually bring about inner change? Recently when an applicant was being interviewed, she asked the brother what Co-Freemasonry had done for him, he replied that it had created order out of chaos, explaining that it had brought order to both his outer and inner life. This is one of the great benefits of long-term practice of ritual: it creates discipline and harmony.

Looking back on my years in the Craft, I see that it has helped me focus on what is most important in life; the unimportant has gradually fallen away. The ritual also has made me more aware of my shortcomings and character flaws and given me tools to work on them. It has provided me with hope and inspiration in times of difficulty, and resolved inner conflict so that I can express Masonic ideals more easily. On a more mundane level, I’ve learned to work more effectively in a group, organize my day-to-day life, budget time, and study regularly.

After a recent initiation, the new sister shared her experience with the lodge and described what it was like for her. With a glowing smile, she said she stilled her thoughts, opened herself completely, and, not knowing what to expect, was still fully trusting. While many candidates can be nervous and apprehensive, this sister was able to really benefit from the ceremony.

Although ritual books can be found, candidates are advised not to read them, so that the ceremony has an element of surprise and is experienced at a deeper level rather than simply intellectually.

A common misunderstanding is that initiation and becoming part of a lodge automatically ensure spiritual development. The ritual is inspiring and gives the energy to move forward, and the support and instruction from other members give a foundation to build on. But growth is ultimately in the hands of each member. This means study, regular attendance at meetings, contemplation of the symbols, and putting their meaning into practice in daily life.

Co-Freemasonry has had its share of problems, just as Theosophy has. In spite of this, the movement has carried on in various forms with the goal of building a unified humanity. The International Constitution of Le Droit Humain states that its members declare themselves “fraternally united in the love of humanity” and seek to give concrete expression “to realize on earth the greatest possible degree of moral, intellectual and spiritual development for all people.” For me there is no higher work than this.

Mary Jo Kokochak has been a member of the Theosophical Society and the International Order of Freemasonry for Men and Women Le Droit Humain since the 1970s. She has served as director of the Olcott Library in Wheaton, and of the Krotona Institute of Theosophy Library in Ojai, California.

The website of the International Order of Freemasonry for Men and Women, Le Droit Humain, is www.comasonic.org.