Printed in the Fall 2022 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Trull, David, "Pachamama, Sisyphus" Quest 110:4, pg 27-28

By David Trull

I am floating in azure water, and I cannot see the bottom. It simply recedes into blacker shades of blue. A thicket of vines dips into this limpid pool, cascading like Rapunzel’s hair from a hundred feet above, conveying the elixir of life to the trees at the earth’s surface. These seem to constantly shed their leaves, which shower me with a shimmering golden snow.

I am floating in azure water, and I cannot see the bottom. It simply recedes into blacker shades of blue. A thicket of vines dips into this limpid pool, cascading like Rapunzel’s hair from a hundred feet above, conveying the elixir of life to the trees at the earth’s surface. These seem to constantly shed their leaves, which shower me with a shimmering golden snow.

Although I do not speak, and my companions are mostly hushed, it is not silent. A flock of swallows is on the wing, careening in circles, round and round, again and again, crying out to each other in encouragement, in joy. Every so often, one of them departs the swarm to take a rest in one of the countless holes in the walls. I figure they must build their nests inside this pacified molten core, which once burned with unbridled fury.

Swimming with placid strokes, I do nothing but take it in: a cenote on the Yucatan peninsula, one of over 7,000 craters left by the impact of the Chicxulub impactor, the asteroid which concluded the reign of the dinosaurs.

A few months before I swam in the cenote, I watched my friend’s four-year-old son for a few hours while she ran some errands. I decided to take him to the natural history museum (one of his favorite places). While the museum had all the usual trappings (fossils of undersea life, a planetarium, Native American artifacts), it was its collection of animatronic dinosaurs that drew children from far and wide.

As my young companion was taking in the roar of a T. Rex and the jerky swings of a stegosaurus’ tail, I began chatting with the docent. Because it had been twenty years or so since I had given much thought to the fate of the dinosaurs, I asked if it was still the current theory that the fearsome lizards met their doom at the hands of an asteroid strike. The docent assured me that this was not only still the going theory, but that scientists felt more convinced of it than ever. It was not only the dinos who vanished after this impact, she said, but three quarters of life on earth. The only survivors were microorganisms and ectothermic species like sea turtles and crocodilians. Small mammals (mostly under 25 pounds) survived, but suffered heavy losses. Burrowing species, because of their sheltered habitats, fared best.

This came as a bit of a shock to me. I had always assumed that only the most complex and fragile creatures—the dinosaurs and other large organisms—had perished from the climate changes brought on by the collision.

Curious, I embarked on a Wikipedia safari that evening. My topic? Extinction events. The Chicxulub impactor, I learned, catalyzed the K-Pg (Cretaceous-Paleogene) extinction event with an explosion equal to a million atomic bombs detonating simultaneously. The force of the impact sent countless shards of the asteroid ricocheting back and forth off the atmosphere, pummeling the earth’s surface over and over. The heat generated by this friction sparked mass fires, which consumed the vegetation across much of North America. Afterward, dense clouds of ash shrouded the planet in darkness for over ten years, halting photosynthesis. It is the most recent mass extinction, occurring about 66 million years ago.

The words “most recent” jumped out immediately. This had occurred more than once? I was startled to find that I was quite ignorant about the matter and continued digging.

The K-Pg explosion annihilated 75 percent of life on earth, but this was not even the greatest of the extinction events. The Permian-Triassic event, known as “The Great Dying,” which took place around 252 million years ago, takes home the blue ribbon for most catastrophic. Over 83 percent of genera vanished, as did 57 percent of biological families. When the Siberian Traps erupted in in this cataclysm, they choked the atmosphere with carbon dioxide, leading to oceanic anoxia (the depletion of oxygen) and acidification. Scientists estimate that it took close to 10 million years for life to rebound from this calamity.

But life did recover from the Great Dying, from the K-Pg event, and from the other horrendous volcanic eruptions and dark decades which pepper the annals of deep time.

I concluded my Wikipedia safari wiser, less naive than before. I had always pictured the evolution of life on earth as one continuous line. Certainly it would have had its ups and downs, like a biological stock market, but it never occurred to me that the entire process of evolution has been halted in its tracks multiple times, left to start over again nearly from scratch. I was in awe of its resilience.

The fact that such devastation has occurred multiple times leaves open the possibility, perhaps the inevitability, that such a grim day will come again. While the odds that I will be alive to experience the next cataclysm are slim, the thought of its inescapable return is a bit soul-crushing. That humanity, should we survive or resurface in something resembling our current form, would have to relearn the myriad lessons of our history, would have to rediscover fire, gravity, and the atom—the idea breaks my heart. I realized that at the end of my imagined straight line of development was some sort of final form, some ultimate realization of humanity’s potential, fully integrated with the universe. Considering the ineluctable extinction events encoded in the geological structure of our planet, is such a condition perpetually out of our grasp? Is evolution a Sisyphean task held at bay by the random crashing of comets and the discharge of volcanic pressure?

|

|

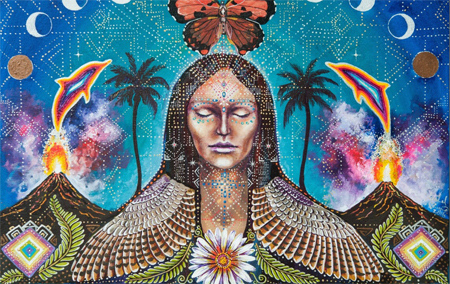

| Venus by Isabel Mariposa Galactica |

As I gazed up at the sky—a golden disk—above me, such fears subsided. It occurred to me how reasonable it was for ancient peoples to worship the sun and the earth. If anything obscures the rays emanating from our star, every living thing perishes. To hinder photosynthesis is to smother life.

During my time in Mexico, I heard much mention of Pachamama. In Incan parlance, she is Mother Nature, the great mother who sustains life on earth. As culture evolves, the ideas of the Sun God and the Earth Mother recede into childlike standing, our dominion over natural forces recasting such beliefs as quaint relics. Yet they are perhaps the most fundamental, if not the most complex, of our spiritual intuitions. When there is a barrier between sun and earth, annihilation is the result. Once the smoke clears, their union miraculously awakens the seeds of life.

I felt that this strange crater, with its orbiting swallows and resplendent golden snow, stood as a monument to this union, to Pachamama and Helios, to life’s irrepressible exuberance. Despite planet-engulfing fires and decades of choking gloom, it would wait patiently for its time to come again. Perhaps some triumphant throne awaits humanity, a future integration of the rational and emotional forces we possess. The cenote is a testament to the endless patience this process requires, the eternal unfolding which must occasionally wait its turn to try once more. As Friar Laurence reminds Romeo and Juliet, “Wisely and slow. They stumble that run fast.”

David Trull has worked as a fireworks salesman, forensic tax researcher, railroad logistician, teacher, songwriter, and musician. He studied philosophy through a Great Books immersion program at Thomas Aquinas College in Ojai, California. A lifelong autodidact, he has advanced his explorations through a self-designed curriculum focused on the intersection of philosophy and theology. Raised in St. Louis, Trull now orbits between Santa Barbara, California, and the San Francisco Bay Area.