Printed in the Fall 2021 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Oliver, Lucy, "Glyn: A Portrait " Quest 108:4, pg 12-16

By Lucy Oliver

We nearly lost him at Summertown, Oxford, in the summer of 1976, when he stepped into the path of a car in the Banbury Road and was just yanked back in time. Saved by a whisker! He was unfazed, but it stuck in my mind as an uncharacteristic lapse of attention in a man whose life work revolved around observation, investigation, and experience, which he called the three modes of attention. In this case, observation had slipped a little out of balance with the other two!

We nearly lost him at Summertown, Oxford, in the summer of 1976, when he stepped into the path of a car in the Banbury Road and was just yanked back in time. Saved by a whisker! He was unfazed, but it stuck in my mind as an uncharacteristic lapse of attention in a man whose life work revolved around observation, investigation, and experience, which he called the three modes of attention. In this case, observation had slipped a little out of balance with the other two!

When Glyn and what we called “The Work” entered my life, it opened a whole new dimension. It was as if I’d been living in a small room with a balcony, only to discover that it was situated within a multiroomed mansion with cellars, garden, and private chapel, all open to me if I chose to investigate. Or indeed, like in Plato’s cave, I could turn away from shadows on the wall and face the authentic world beyond, if I held the intention to do so.

How does one recognize such authenticity, especially if it is not on a dais with flowers addressing a multitude?

I think of Glyn in any social context. What did he speak from? He needed no props, no badge, and you listened—a whole room would gravitate round this stocky little figure with the long hair, nicotine-stained fingers, and cigarette burns on a grubby jumper (sometimes turned inside out for the benefit of the clean side). He could look more presentable in clean gear and jacket on public occasions, but the shoes usually had no laces, just holes—he had a thing about laces.

Not everyone was enchanted, however. Some ran a mile, and he terrified others.

When you looked into his eyes you saw no thing, no one. Just a vast space.

His angle of vision was always unexpected, but always coherent, and when you examined it, it opened up new ways of thinking. When I first met him in the early seventies, he was just embarking on his phase of gathering people to help with his self-generated task of reformulating old philosophical ideas for modern understanding, particularly the Kabbalah, which was the basis of his training. In the newly enlivened esoteric and spiritual context of London in the sixties, new ideas arriving from the East mingled with a rediscovered Western heritage. Magic, mysticism, meditation, astrology, esoteric lodges, spiritualism, and theosophy were supplemented by elements from Jung and psychoanalysis, and the Gurdjieff-Ouspensky work presented a demystifying corrective to exotic and florid hocus-pocus. Glyn emerged from all this with a clear sense of a job to be done: to unclutter the fantasies and superstitions which accrete round any religious or esoteric way, and look to first principles in the roots of actual experience.

His bearded face was open, well shaped, and his gaze steady and appraising. Around his eyes were crinkle lines. The eyes usually gleamed a little as he looked at you, and a rumbly laugh was never far away, shaking his form quietly at the absurdity of the human condition. “Hours of innocent merriment” was a stock phrase. He would mischievously apply it, sometimes to an apparently serious endeavor, either his own or some other exercise in which a great deal of pompous self-investment was evident.

The Kitchen

His headquarters for nearly forty years was the Kitchen, tucked away at the back of a typical old west London apartment block. The Kitchen modified slightly over the years, but in general it presented mushroom-colored walls with a huge brown and yellowing Tree of Life emblem on one wall, and another circular diagram painted on another. Glyn would preside from a large, ancient chair, and all others would perch on a variety of old wooden chairs, some minus their backs, and one other semicomfortable, albeit elderly, armchair. Ashtrays abounded, and in the early years, your eyes would sting with the smoke haze, as most people smoked continuously. A rickety window would sometimes be propped open with a pole, allowing a freezing draft to circulate round your feet, which turned into solid blocks by the end of the evening. Glyn rolled his own cigarettes from a round yellow tin of Boar’s Head tobacco. In later years, concerned for his health perhaps, he inserted the wobbly fag into a holder, initially constructed himself from a ballpoint pen. Later he graduated to proper holders, but the elegant impression was always pleasingly incongruous.

In addition to aching buttocks and back, stinging eyes, and feet like ice, one’s upper section got rather warm. My face used to flush like a tomato from the heat of the single gas burner on the grubby stove, which was the sole form of heating in the winter. I learned to wear thick boots if possible, and old clothes that could go straight into the wash, as the smoke penetrated right to vest and bra. This used to amaze me as I picked them up next morning, smelling as if I’d been barbecued the night before.

Glyn’s entertainment came from devouring fiction, especially science, and from an old television perched on a cupboard. He enjoyed watching what we tactfully called “his rubbish,” and would often make you wait if you sprang on him unexpectedly, until some cop drama or the hapless geriatric escapades in the sitcom Last of the Summer Wine (a particular favorite) had finished.

I never quite fathomed where his vast erudition came from, especially in pre-Internet days. He kept up with documentaries, of course, and had read very widely for many years, with a reading card at the British Library, which partly accounted for his extensive general knowledge and ability to discuss the most minute detail of just about anything with just about anyone. But it was the way he processed information which was unique. He incorporated it into some internal processor unlike anything I have ever encountered. He handled maths and scientific concepts with precision, and used them in the reams of delicate and detailed diagrams he generated constantly to back up, and indeed inspire, his metaphysical theorizing.

Glyn’s background was in electrical engineering and accountancy, and he was an intensely practical man. He loved to make things, and to make things work. He called it “bootstrapping,” a term derived from his days in the Royal Air Force after the war. Bootstrapping, as I understand it, meant you picked yourself up by your own bootstraps, not relying on anyone else. (A gymnastic feat, but worth the effort!) For example, part of ritual training was making things from the most basic materials, not purchasing them ready-made. To make a knife for ritual purposes, you boiled up the fish oil to make the glue, cut and tempered the blade in a fire, twined a rope together, and used it to wrap into a handle. That kind of basic! The physical was an analogy for other levels of operation. “Back to first principles” was the most fundamental aspect of his teaching.

The Kitchen was not a serious place. He liked to laugh, and in keeping with the “no guru” rule, we all took the mickey whenever we could. It was an achievement to make him laugh, so we all tried, and he enjoyed witticisms. Puns were a special favorite, and he came up with some delectably awful ones himself.

He was immensely patient, though, with all the raw young talent he constantly had to deal with. We would ring up and ask to come around then and there, somehow assuming he was always available for our benefit, or would always be pleased to discuss the solemn ideas of aspiring Knowledge seekers. He almost never refused, and welcomed you with a quizzical look as you walked in the door, assessing where you were at. “What news?” he’d say, leaning back in his chair and puffing.

The conversations would go on into the small hours. It was common knowledge that the best stuff happened well after midnight, so we would wait it out, feeling the feet solidify and the cheeks start to burn. The conversation got deeper. If there had been an assorted crowd in the kitchen (you never quite knew who would be there, or from how far away), the less determined gradually peeled off and went home, leaving the hardy to push the conversation into more intimate areas of metaphysics or gossip. It was like being fed. You finally stumbled off into the silent streets, hoping your car hadn’t been boxed in by double-parking, feeling replete and inwardly humming with a sort of psychic food, and possibly pages of scribbled notes. A visit to Glyn provided many weeks of internal stimulus.

His various personal peculiarities included not liking to have his hair cut (like Samson, I used to think), and it was most often tied into a ponytail behind him. The absence of shoelaces was owed to some very rational justification which I quite forget (he was heavy-footed when he stood and walked), and he went through a phase of wearing a bizarre housedress, like a jellaba, made by his wife, instead of trousers. More comfortable, he asserted, flicking the ash down his rotund middle, where little holes appeared, and a few assorted stains.

Once he startled us all by briefly shaving off his beard. It was not popular, as his chin was unexpectedly small. Normally he had the face of a traditional prophet or guru: an ample greying beard and moustache, well-proportioned nose, and eyes which saw right into your soul and into the soul of the universe. It was a noble head. He looked the part.

You could get lost in the eyes. Later in his life I used to deliberately stare into them, trying to see how far I could go, or if I could find anything. Because later in life he lived more and more on what has been called “Planet Glyn,” it was harder to connect with him. His voice sometimes trailed off as if he realized that people weren’t following, and indeed I often was not. He also wept. Tears would just emerge as he talked, especially at the mention of anything carrying a certain type of emotion—you could call it higher emotion, which wasn’t personal and involved humanity at its best: tales of people doing kindnesses, the ritual of royalty, the ethos of the British Commonwealth, accounts of death or birth. He would wipe his eyes and carry on talking.

His presence carried such charge that once, leaving, I got as far as the front steps before the whole fabric of my being seemed to disintegrate into a huge void. What was left stood pressed against the door, the rest blown away; everything I thought was me, gone. What I’d come to talk about was completely obliterated. How did that happen, I thought? We had just chatted.

He never ceased producing material, right up to his final brief illness, methodically sketching neat little diagrams, transposing figures, weighing up propositions and terminology, and generating new angles and theory to reformulate the laws of the Eternal. It was always unexpected. He could turn things on their heads and would try out new ideas on everyone who came through the door. We were his sounding boards. He liked to be challenged and to engage in a good argument, testing out what worked and what didn’t. His regular revisions of theory kept us all busy for nigh on thirty years, exploring and developing what he expounded as the latest way of looking, religiously copying the latest diagram to take back to whatever groups we were in. “Glyn’s new diagram” was a prize to be shared.

In later years fewer people came, but he never stopped generating, late into the night when all was quiet, and throughout the day as well.

He was always interested in other people’s productions too, and was pleased when someone had done some original work. He regularly threw out titbits of ideas and stimuli, hoping they would be picked up and developed. Often they were too far out for the recipient to be able to relate to, and fell on fallow ground. In the early years when we were running a center, he was an active, almost explosive presence, directing, steering, pulling extraordinary rabbits out of hats, and generally creating an atmosphere of sheer magic and high adventure. The world was always richer around Glyn; the curtain of the mundane world pulled back to reveal wonders; the spirit bowed down to earth and was just about graspable.

|

|

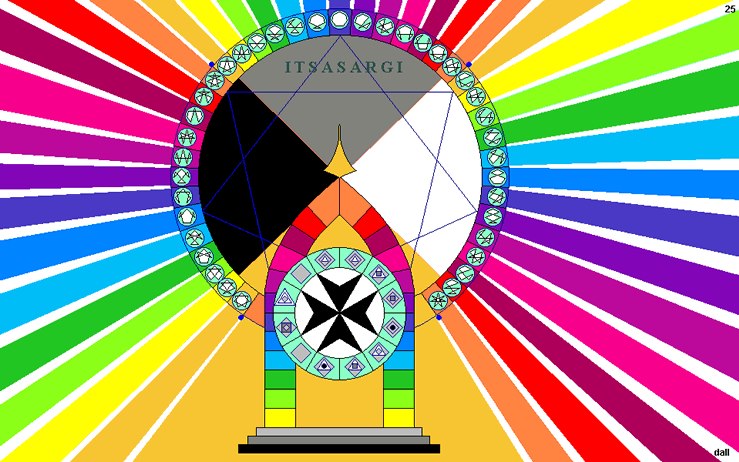

| Lighthouse,” one of a series of sixty-four diagrams forming Sareoso, Web of Wholeness, Glyn’s final compendium of the principles of creation. Image from www.sareoso.org. |

He was never unkind; irritable sometimes, ruthless when need be; humble, he kept nothing for himself, owned practically nothing, and refused all charity, even, if possible, from the state. Until pensionable age he mostly worked, but had very little money. After a heart scare in middle age, he refused the recommended pacemaker, declining to have a mechanical object in such a symbolic role. Responsibility for your own actions was a rule he taught and lived by. He could be fierce, and dealt harshly with some of the men on occasion. There was always a little frisson of trepidation when going to see him, as cherished notions might get knocked for six, but I remember going to see him once, expecting a rap over the knuckles for something and met only kindness and gentleness. I came away with my heart rejoicing, and feeling unexpectedly stronger. Visits almost always tuned you in to something greater and reminded, one way or another, but you could never be sure which way.

He trained us thoroughly in all the traditional esoteric skills and practices, if only so there would be no veil of mystique. “We are generalists,” he would say. Specialized in no particular area, a generalist has a little experience of all, enough to know the basic principles and be able to design or recreate should the knowledge be lost. It gives a very clear-eyed and sober appreciation of how the psyche works to generate human life and interaction, and is excellent insurance against glamour and inflation. “As necessary” is the golden rule. Speak and act only as necessary.

Authority

He had a personal rule of which he regularly reminded all who came: he would not keep secrets. Everything was passed on. It was a way of preventing the confidences of the self-important (which we all were) from accumulating round him, and then being used to manipulate him or others. (such as asserting authority: “I went to see Glyn, and he . . .”) It was not possible to manipulate Glyn. He kept nothing for himself and owned nothing, material or other.

I frequently had the experience of hearing something I had told to him repeated back to me by someone else, particularly if it reflected badly on me, and someone was trying to set me straight! Galling, but effective. So much human interaction consists of power games, trying to steal a march on another, present oneself as important, thoughtful, clever; to imply that one has the approval of an authority figure. But Glyn wouldn’t play.

“Authority is given, not taken. People give authority to others, be it wise or unwise” was his stand on the cause of so much grief and violence as it plays out in the world.

By repeating to everyone who passed through his kitchen whatever was current, he prevented any logjams of personal authority. It was not for the sake of gossip, though he liked to know what was going on, but any personal stuff was fair game for sharing. Deeper matters, such as meditation checks or more profound conversations, were safe, however. You instinctively learned to tell the difference. Passing it on was more likely if the issue seemed personal, secret, or power-seeking.

This practice was one of his deadly tricks to puncture self-importance, which is the greatest obstacle on a path of Knowledge. The greatest challenge for a teacher is the task of helping others to get beyond their natural egotism in a way which doesn’t diminish them, but encourages growth and development of Being. It’s one thing to give out teachings, but creating conditions to provide the shocks and provocations for change and self-insight is quite another.

So, despite his protestations not to give him authority, naturally everyone did, and sought his approval and imprimatur stamp for their ideas, theories, and projects. One of two things would happen. The Great Project might evaporate before your eyes once you’d aired it in his presence, and for no very clear reason, because there’d been no criticism. Or he chattily explored it with you, using it as a jumping-off point for whatever was preoccupying him at that time. You went away pleased, and somehow convinced of his approval. Except he hadn’t actually given it. He’d just encouraged you to do more of what you were determined to do anyway.

Rather than trying to change people or their ideas, he maintained it was often better and more useful to reenforce them, so that if there were cracks or weaknesses, they would become apparent to the person him- or herself sooner rather than later. If there is a crack, widen it. If a weakness, drive a wedge in. He employed this strategy consistently, and articulated it frequently as a useful methodology. “Make the inevitable happen.” Hence people would make their own assumptions along the lines they desired, and would depart with a comfortable assurance of authority bestowed.

However, because (a) you had accorded the authority yourself, and (b) there were no secrets, quite often your plans would later sneak up and hit you in the back from another quarter, because he would have told everybody, and probably not in the flattering terms you might have wished for. Others would gain a different impression of whether or not he approved!

In all this Glyn was absolutely up-front. He told everyone his strategies as a teaching point, but it was hard to believe him when it came to oneself. They were simple principles, consciously employed, and he would sigh and shake his head theatrically when he was accused of manipulating. He faced these accusations often, because it is human nature to invest authority in others, and then blame them if your expectations are not met.

I think Glyn made such an issue of authority, and of his own nonguru role, because there is no issue more important in the individualist and turbulent age we live in than understanding the nature of authority. The question To whom or what are you giving authority? underlies every conflict situation, every ideology. It is the nub of morality, aggression, victimization, and all “beliefs.” Secular humanist philosophies give ultimate authority to ourselves as humans. Others bestow ultimate authority on something outside us: Spirit, Consciousness, God. And finally, when artificial intelligence mimics human intelligence, will we give or withhold authority to the algorithms which apparently know us better than we know ourselves? What would that mean in practice?

These are not academic issues, but day-to-day realities. Just about all human interactions are shaped by authority and the power which goes with it. The principle that authority is given, not taken, is transformative and fundamental, and Glyn lived it out with every person he encountered.

Self-responsibility means standing on your own feet. Otherwise “where will you be when your One has passed away?” as it says in The Book of Jubilee, an esoteric text produced in Glyn’s circle. His methods were based on a view that the essence of Knowledge is common to all humanity, and on equality and self-responsibility, but did not pander to natural egotism, ambition, or the wish to be given the fruits of wisdom and peace without effort. He set up situations in the early years when he was still actively engaged in training, but it was for purposes of the Work, not to play with people.

He could travel into the future with an enormous vision of humankind in the multiverse. And into the past, with an impressive knowledge of history and a unique way of seeing relationships and the forces governing events. Forty years ago, when Islam seemed a benign, quiet presence on the world stage, I remember him warning that the big trouble to come was going to arise from Islam. It surprised me, as at that time many of us had links and great sympathy with Sufi groups and saw Islam mainly in terms of profound Sufi mysticism. I think of his prophecy every time a new Islamicist atrocity hits the headlines.

One day he announced he was learning Basque, a language with a unique root among languages and confined to a particular small area in the world, and where he intimated there could be an old tradition of knowledge. He found and hired a tutor and studied his dictionary diligently. With its help he then translated and presented in Basque some contemporary formulations of ancient principles (see www.sareoso.org). That it would require considerable effort to access them, reflects their value, and “burying the bone deeper” is designed to activate the teachings, not conceal them. It’s especially salient in an age when everything appears accessible and just there for the taking. Growth through consciousness is never like that.

He lived longer than he expected, having withdrawn from active steering in most capacities long before, and offering only “technical advice” for many years. He had a little pottery urn made all ready for his ashes, and everyone passed it daily as it sat on a shelf in the dim hallway. He seemed to have been preparing for a long time, and was entirely ready to take a journey into the realm of “the Player on the other side,” as he liked to refer to the Divine mystery. You felt he loved that Player. He would talk God in any one’s language, quoting from mystics, Christian, Kabbalist, Buddhist, or from any other tradition, emphasizing that the God we know is “God in you.” Some conversations about the spiritual that I had with him seemed to leave the earth; I only took away fragments jotted down afterwards, but the impression of an immensity opening up was awesome.

It wasn’t even in the words; it was something about the space created in his presence, and love was in the space.

Lucy Oliver has been a teacher and practitioner of meditation derived from the Western esoteric tradition for over forty years. Her book The Meditator’s Guidebook k has been in print since 1996. She lives in London, and after studies in sacred symbolism at Oxford University, has developed Symbolic Encounters, a method of pointing out the symbolic roots in language on a path of knowledge (www.meaningbydesign.co.uk). She was a founding member of Saros Foundation for the Perpetuation of Knowledge and of High Peak Meditation, established in the United Kingdom in the 1970s. This chapter is excerpted from her latest book, Tessellations: Patterns of Life and Death in the Company of a Master (published by Matador), an insider’s view of working within a Western oral tradition.