Printed in the Spring 2019 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Richard, Smoley,"From the Editor’s Desk" Quest 107:2, pg

Christianity and Buddhism both speak of love and compassion, although in different proportions.

Christianity and Buddhism both speak of love and compassion, although in different proportions.

For Christianity, love has always been the primary value. The New Testament even says, “God is love” (1 John 4:8). But Buddhism, particularly in its Mahayana form, speaks more often about compassion.

This difference says something about the two religions. What is love? It is that which unites self and other, while preserving the integrity of each. (For more on this, see my book Conscious Love: Insights from Mystical Christianity.) Love does not presuppose suffering. You can love someone whether he or she is suffering or not.

Compassion, on the other hand, inevitably includes an element of “feeling sorry for.” It is hard to feel compassion for someone who is enjoying perfect bliss. Hence the centrality of compassion for Buddhism. The central premise of Buddhism is dukkha—suffering, or, if you like, dissatisfaction. All sentient beings—from the gods in the highest heaven down to the beings in the hell realms—are subject to dukkha. The only appropriate response is compassion.

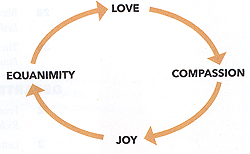

How, then, is compassion related to love? The most elegant and profound answer to this question comes from Mahayana Buddhism, with its teaching of the four immeasurable catalysts of being. They are love, compassion, joy, and equanimity. They operate in a cycle.

Let us begin with equanimity. This is total freedom from attachment—“becoming impassive about those near and far,” as the thirteenth-century Tibetan sage Longchenpa puts it in his Trilogy of Finding Comfort and Ease.[*]

We can see a difficulty here. Equanimity, taken to an extreme, can lead to a pervasive indifference or obliviousness.

How do you counteract this inner torpor? With “a supreme, all-encompassing love greater than the love a mother has for her only child” for all beings. But love contains the potential danger of attachment, as we see in most human relationships.

What do you do then? Develop compassion by thinking of the suffering of all beings “in the same way as you are unable to bear mentally the suffering of your parents,” says Longchenpa. He adds, “the inability of bear the suffering of living beings is the indication (of compassion).”

Nevertheless, this relentless focus on suffering can become depressing. The way out of that is to cultivate joy:

Ah, there is no need for me to install

All these beings in happiness;

Each of them having found his happiness,

Might they from now onwards . . .

Never be separated from this pleasure and happiness.

But with joy, taken to an extreme, “the mind is agitated and becomes overexcited. You have then to cultivate equanimity, which is free from the attachment to those near and far.” And the cycle begins anew. We can picture it in this way:

Longchenpa advises starting with the cultivation of love, then moving on to compassion, joy, and equanimity. Eventually the practitioner “may then cultivate the immeasurably great properties in their order, outside their order, in a mixed order, or in leaps and bounds.”

This teaching is the most profound and powerful that I know of about the relation of compassion to the other principal virtues. It is echoed in Aristotle’s teaching that all virtue is a mean between two extremes. Compassion is a mean between apathy and a sentimental but debilitating pity.

I think it would be wise to contemplate this teaching today, when many people overexcite themselves—even in the name of compassion—in the belief that this agitation is a virtue. Agitation and upset are never beneficial, even when supposedly in the service of the highest ideals.

Richard Smoley

[*] I am quoting from Longchenpa, Kindly Bent to Ease Us, Part One: Mind, trans. Herbert V. Guenther (Berkeley, Calif.: Dharma Publishing, 1975), chapter 7.