Printed in the Summer 2022 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Braun, Stephen, "Beauty and the Joshua Trees" Quest 110:3, pg 23-29

By Stephen Braun

A very specific quest for beauty started in the Mojave Desert, in the part of that desert where the Joshua trees grow. It started ten years ago, when I first experienced them. I have always loved trees, but those captured my heart and attention like no others.

A very specific quest for beauty started in the Mojave Desert, in the part of that desert where the Joshua trees grow. It started ten years ago, when I first experienced them. I have always loved trees, but those captured my heart and attention like no others.

They sit apart, dotting the sunburnt horizon as far as the eye can see. They are prickly and tawdry-looking; they live without much water and grow with a form that is ideal for discouraging predators and pretty much all else in the world. These rare trees exhibit no traces of animated life, showing what appear to be constant signs of distress, with limbs torn asunder here and there. There is constant heat and little wind in the desert, so they remain still; one will never see a Joshua swaying and dancing in the wind. Their prickly exterior ensures there will be fewer animals or birds to be found among their branches than on other trees.

Some find Joshua trees to be exceptionally beautiful; others, who notice the spiny, wayward, and prickly features, find them odd-looking. But are we seeing them as fully as we can?

Seemingly alone and separate from one another, they each offer a unique and individual voice as one moves among them. There is a sense they have something more to share with us than meets the eye, that they want to be heard. Perhaps they can offer something from their world to ours, something revealing, and exceptionally beautiful, about their inner nature.

The Mojave Desert is a bit out of the way for a New Yorker who doesn’t drive, but I managed to get there several times over the years to commune with those trees. On each occasion, I attempted to hear what they might have to say or share. I started to consider how, as a photographer, I might be able to capture that with a camera. I wondered how I could portray their inner voice and beauty in a way we might be able to understand as busy humanity, blessed with our human set of senses and abilities, which are much different from those of the Joshua trees. In the words of Susan Sontag, author of On Photography, one of the most seminal books about photography as an art form, “Nobody ever discovered ugliness through photographs. But many, through photographs, have discovered beauty.” This essay is about how I did just that, with inspiration from the Joshua trees.

|

| Joshua trees, Joshua Tree National Park |

Photography may seem like the epitome of Plato’s cave. Light from the external world enters a lens and is affixed on a plate; the image from said plate is then rendered onto a medium elsewhere, at which point we have what may be considered a photograph. This aspect of photography used to limit how its potential was regarded and the extent to which photographs were counted as a true art form.

As tools have progressed, those opinions have started to change, and photography has begun to earn the reputation it deserves in the canon of fine arts. However, one thing has not changed since the first click of the shutter of a camera obscura until today: photographers have always been concerned with finding the beautiful in unexpected places, or amplifying beauty in places where it is expected.

|

|

|

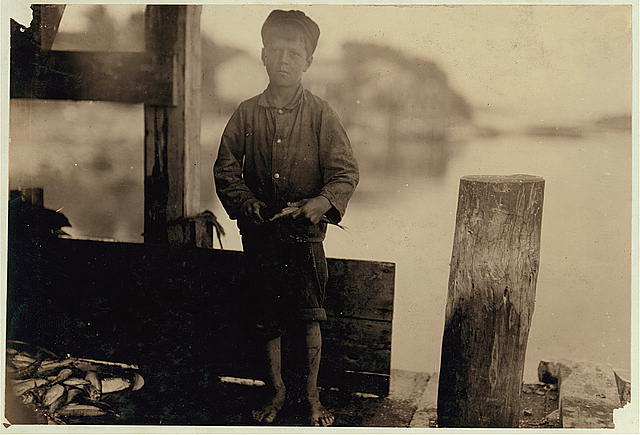

| Figure 1. This work, a study of rose of Sharon flowers by Adolhe Braun (c. 1854), is an albumen silver print from a glass negative. Some might say that flowers as an object are undoubtably beautiful, and therfore this image is. Others migt look at the unusualcomposition of this image and disagree. | Figure 2 Hiram Pulk, nine tearsold, cuts some fish at a canning company. "I ain't very fast, only about five boxes a day. They pay abot 5(cents) a box." Eastport, Maine. National Child Labor Committee collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Offhan, if we described an image of a young boy with soiled clothing and dead fish next to his bare feet, a dock slightly out of focus, with skewed angles, adn gray skies, one might not imagine it as beautiful. And yet when looking at the image, taken by Lewi Hine to document child labor, many might yet see beauty. What, then, makes this image beautiful? |

Of course, cameras also serve utilitarian purposes, such as for documentary or archival photography. But this essay will focus strictly on the camera as a tool for unlocking and identifying more beauty from and in our world.

Like many other artists, photographers have attempted to define beauty as subjectively or objectively based, and they have run into the classic problems and tug of war between the two, as in this example (figures 1 and 2).

The above examples represent conundrums for defining beauty in a photograph, since not everyone would agree on whether each image may be described as beautiful. This has led some to state that beauty is intersubjective, in the sense that it is dependent on a group of judges. But this leads us to even more problems: there’s simply too much beauty in this world and too many judges to see us through to a concrete definition.

|

|

|

Figure 3: This photograph of the Fontainebleau Forest in France, by Eugene Cuvelier, dates from the early 1860's. Many would agree that this magical photograph of a magical forest effectively captures sublime beauty. The image might arguably pass muster with both the objectively an subjectively defined concepts of beauty, leaving us with yet another conundrum, because both defintions aply. |

Finally, we have a third example to consider:(figuare 3)

Initially, photographers had only a limited ability to capture a point of view different from what we are capable of seeing as humans. From the early camera obscuras of the beginning of the nineteenth century until the early twentieth century, photography was very much what-you-see-is-what-you-get, provided subjects could sit still for half an hour or a fifty-pound camera could be lugged to a site. In its earliest days, photographers strove for what-you-see-is-what-you-get, given the difficulties of lighting conditions, early stages of camera equipment, and atmospheric proclivities.

As cameras became more portable and procedures for capturing photos became more process-oriented, photography proceeded to document wonders, civilizations, and beauty throughout the world. Photographs of pyramids, Amazon rain forests, Chinese temples, and the Eiffel Tower spurred interest and excitement to capture more and more beauty.

This early expansion established photography as a medium that was able to capture the world in ways that were considered both factual and fascinating. This new ability to affix light to a silver-coated plate, then use light again to fasten an image from that plate onto a photographic canvas, unlocked new potential to account for detail in the world and humanity. “The photographer,” Paul Rosenfeld wrote of Alfred Stieglitz, “has cast the artist’s net wider into the material world than any man before him or alongside him” (Sontag, 24).

After photography became more established as a medium, some photographers sought to break away from the what-you-see-is-what-you-get relationship between normal human perception and what is being photographed. Early historical breaks from our typical anthropomorphic viewpoint began to move photography into its own unique direction as an art form. This expansion beyond what we typically would notice with our own eyes started in the early twentieth century, with pioneers such as Paul Strand and Edward Weston, who attempted to portray patterns and beauty in unexpected places. With their work and that of other pioneers, photography started to move forward as an art form on its own terms.

|

|

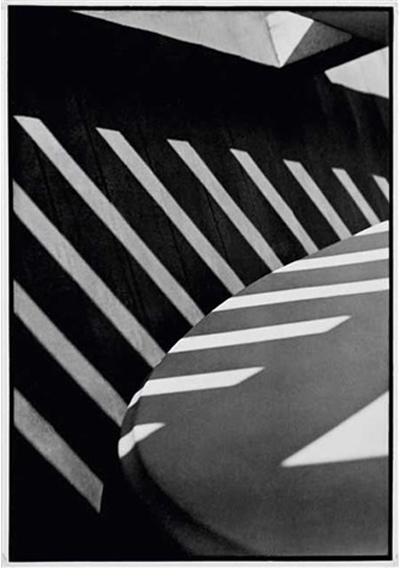

| Figure 4. Paul Strand, Abstraction, Porch Shadows, Connecticut (1916), gelatin silver print, from the porfolio On My Doorstep, A Porfolio of Eleven Photographs, 1914-73. |

In 1915 Paul Strand, who studied under acclaimed photographer Alfred Stieglitz, took a photograph which he titled “Abstract Patterns Made by Bowls,” one of the earliest known attempts at such a perceptual shift. Strand later turned to close-ups of machine forms, nature, and nudes, pulling the curtain and revealing previously unrecognized beauty in both natural and man-made forms. In addition to honing in on macro shots of everyday objects, Strand also played with perspective. His From the Viaduct, New York (1916), showed a new kind of artistic perspective that could be unleashed by the optics and field sensitivities of cameras.

Strand’s work is one of photography’s earliest and best-known breaks from showing the world strictly from our existing perspective. Work like his enabled photography to reveal novel structures, patterns, and beauty in everyday settings and objects. The photographic floodgates were now open, and many photographers have followed suit to this day. (figure 4)

Subsequent advances in camera technology eventually went in numerous other directions, bringing us images of earth from orbit or from vast depths under the sea. We became able to recognize and account for breathtaking beauty in our world that was inconceivable a few generations ago.

Photography now has become known for exploring symmetry, structure, and harmony in the nooks and crannies of our material universe. Susan Sontag writes, “One finds that there is beauty or at least interest in everything, seen with an acute enough eye” (Sontag, 138). Indeed, that is the lifelong quest for many photographers: to unlock beauty and share it with the wider world.

Photography was not generally considered a fine art until the 1970s, when On Photography made probably the most valid and convincing case for it. In that seminal essay, Sontag addressed many aspects of beauty in terms of the photographic medium. When discussing how photography compares to painting, she said, “The painter constructs, the photographer discloses” (Sontag, 71). That prevalent view of photography has been a mixed blessing for the craft, inasmuch as it has led many to discount it as an art form. Yet when a photograph approaches the sublime, we are acutely aware of its potential for transcendence. This too has also made it difficult to pin down succinct definitions of beauty in photographs.

As camera, optical, editing, and storage technologies developed, we have been able to see more beauty in the material world than ever before. Breathtaking images of cellular biological structures are now possible, as are images of the far reaches of outer space, revealed by our cameras: (figures 5 and 6).

|

Figure 5. (ABOVE) Cameras in space have revealed breathtaking cos,ic beauty and universal essence. Image courtesy of NASA. Figuar 6. (RIGHT) Our space cameras also have revealed harmnic patterns and laws underlying our universe. Image courtesy of NASA. |

|

|

How might we apply twenty-first-century photographic tools to Joshua trees? One suspects that those trees can sing louder for us, no matter what kind of subjectively or objectively based photograph we take.

We can pursue this quest further by considering the problem from a Theosophical point of view, using ancient wisdom.

Theosophical Concepts of Beauty

Perhaps we are limiting ourselves with the subjective-objective paradigm to which we default as photographers. What if we were to think less about taking a photograph “of” something and more about “constructing” a photograph using the ancient wisdom? A photograph records the relationship one object has with another: a photographer-object taking a photograph of another object. So then, what if we consider a photograph as a connection between objects, or what if we use photographic tools to explore the inner relationships of an object on its own?

Let’s look for some of the answers by going back to the Stanzas of Dzyan:

This was the Army of the Voice—the Divine Septenary. The sparks of the seven are subject to, and the servants of, the first second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth, and the seventh of the seven . . . These (“sparks”) are called spheres, triangles, cubes, lines, and modellers. (Secret Doctrine, 1:93)

Philosophers through the ages have attempted to express the above wisdom by portraying it in different ways through the concepts of form, number, geometry, harmony, and symmetry; the unifying essence of which points to a divine and loving intelligence embedded in manifested creation, which they called beauty.

The Pythagoreans were able to express the fundamental principles of the universe through numbers and form. Plato in the Symposium and Plotinus in the Enneads define beauty itself in the realm of the ideal Forms, and the beauty of particular objects in their participation in the Forms.

The eighteenth-century Irish philosopher Francis Hutcheson states, “What we call Beautiful in Objects, to speak in the Mathematical Style, seems to be in a compound Ratio of Uniformity and Variety; so that where the Uniformity of Bodys is equal, the Beauty is as the Variety; and where the Variety is equal, the Beauty is as the Uniformity.”

|

||

| Figure 7. The Dance of Shiva: six photographs overlaid using seal of Solomon geometries, number sequences, and Tarot symbolis,. |

The Roman architect Vitruvius writes, “Symmetry also is the appropriate harmony arising out of the details of the work itself . . . As in the human body, from cubit, foot, palm, inch and other small parts come the symmetric quality of eurhythmy.”

Thomas Aquinas’s second requirement for beauty is “due proportion or consonance.”

The question becomes: how do we apply these ideas of beauty to a photograph? It may be to our benefit to consider a third aspect of beauty—one that considers it in a transitive sense, as informed by patterns within and among conscious objects. If we start to consider beauty this way, and identify harmonics and patterns transitively, what might happen? How might we unlock those patterns in a tree?

We are at an exciting moment for applying the use of ancient wisdom to images. Photography, at its core, is about mathematics and light. As beginners, we were taught the “rule of thirds” as a means of structuring the composition of a photograph. (The term refers to a type of composition in which an image is divided evenly into thirds, both horizontally and vertically, and the subject of the image is placed at the intersection of those dividing lines, or along one of the lines.)

When we take a photograph, we are implicitly managing a complex series of mathematical considerations, sequences, and decisions that determine the various settings of a camera and how the resulting image is affixed to a final medium. We have light meter settings, lens refractions, color settings, flashlight strength and duration, shutter speeds, f-stops, distance from the subject, depth of field, and other mathematical considerations that are required every time we take a photograph, even with a mobile phone. Many of us may be unaware how many of these considerations are automated when we use contemporary cameras.

|

|

|

| Figure 8. Maple grove, Naperville, Illinois. Thirteen photographs, full circumference, with Tarot and sared number sequences to inform setings. | Figure 9. Forest bathing, Fairbanks, Alaska. Thirteen photographs, full circumference, with Tarot and sacred number sequences to inform, settings. | |

|

Figure 10. (ABOVE) Birch grove, Fairbanks, Alaska. Eleven photographs, half circumference, with Tarot and sacred number sequences to inform settings. Figure 11. (RIGHT) Spruce mandala, Fairbanks, Alaska. Five photographs, half circumference, with Tarot and sacred number sequences to inform settings. Note the mandala pattern, which appeared when I applied the final esoteric adjustment. |

|

|

Photographers make explicit choices about those elements to move their concept and image forward. We now have the ability to take things a step further by incorporating esoteric teachings and paradigms into the mathematics of photography. We have more potential than ever to explore universal harmonies with our cameras. Most image editing software easily allows millions of combinations of the mathematical elements of a photograph, down to the pixel level. Optical lenses are more advanced than ever. We have almost limitless potential to apply esoteric tools in new ways.

The key is to find ways of incorporating esoteric principles into our use of cameras and other imaging tools, in the ways our cameras interface with the external world, and in the settings of the photography tools themselves. The esoteric possibilities are practically endless.

Now let us return to those odd-looking trees in the Mojave Desert to test the transitive aspects of beauty in photographs. I returned to them last April, on my first photographic journey out of New York City since the start of Covid-related lockdowns. This time my journey was different: I was now accompanied by teachings from the ancient wisdom in addition to my trusty camera. I wandered the desert on foot, considering different trees to work on; when a hawk landed in one of the trees near me, I knew it should be the one for attempting a new approach to beauty in a photograph, using ancient teachings.

To start with, I selected six stones from the desert floor and laid the first one to the north of the tree. I then marked out a six-pointed star (sometimes called the Seal of Solomon), with the first stone set at the top of this esoteric symbol, followed by placement of the other stones at angles where I could attempt to capture the tree’s living harmony. I took a series of photos of the tree from each stone, using esoteric concepts to inform intentional camera movements and the angles of my shots. My goal was to capture more of how the tree itself experiences and lives in this world, differently than we do, but in its own beautiful way.

Once home, I completed the last phase of this process by combining the photographs I had taken into one. I sequenced the photographs and applied adjustments to them using esoteric tools such as numerology, harmonic ratios, and Tarot symbolism. The result from this first attempt was encouraging:

Encouraged by this result and subsequent attempts, I started to apply techniques rooted in the ancient wisdom to trees across the United States in a new project called American Tree Portraits, which so far has included trees from fifteen states. The results have been startling, and a nascent body of work has started to emerge.

And now let us return to the Joshua trees and the inspiration of the Mojave Desert. They have shown us new ways to find beauty by applying esoteric tools within camera settings and the imaging process., We may now bring more voices and beauty to life as the trees sing and dance for us, enriching our loving world even more. We may also look at our modern cameras as ubiquitous beauty machines, which allow us to explore, capture, and share more beauty than ever, pulling the veil off the harmony and intelligence in our divinely manifested world.

Sources

Blavatsky, H.P. Meta-Astronomy. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Concord Grove Press, 1982.

————. The Secret Doctrine. Two volumes. Wheaton: Quest, 1993.

Fistioc, M.C. The Beautiful Shape of the Good: Platonic and Pythagorean Themes in Kant’s Critique of the Power of Judgment. Reviewed by S. Naragon. Notre Dame, Ind.: Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews, 2002.

Hegel, G.W.F. Hegel’s Aesthetics: Lectures on Fine Art. Translated by T.M. Knox. Oxford: Clarendon, 1975.

Hutcheson, Francis. An Inquiry into the Original of Our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue: In Two Treatises. In K. Haakonssen, ed. The Collected Works and Correspondence of Francis Hutcheson. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2004 [1726].

Kant, Immanuel. Critique of Judgement. Translated by J.H. Bernard. New York: Macmillan, 1951.

Konstan, David. Beauty: The Fortunes of an Ancient Greek Idea. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Newhall, Beaumont. The History of Photography. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1982.

Rosenheim, J.L. Photography’s Last Century: The Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Collection: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2020.

Sartwell, Crispin. “Beauty.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2017.

Schiller, Friedrich. On the Aesthetic Education of Man. Translated by R. Snell. Minneola, N.Y.: Dover, 2004.

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1977.

Troward, Thomas. The Hidden Power and Other Papers upon Mental Science. New York: Robert H. McBride & Co., 1925.

Stephen Braun is a writer and photographer based in New York City and a Life Member of the Theosophical Society. He is active with the National, New York City, and Washington, D.C., lodges. More tree images created using esoteric tools may be found at www.stephenbraun.photos.